Another very interesting study which explored whether it’s possible to identify if an organisation is prone to having major accidents on the basis of their safety culture (SC) assessments based on a specific accident.

The author compares descriptions of the organisation involved in the Snorre Alpha accident before and after a major incident that occurred. They drew on culture survey data before the incident and the accident investigation report.

The author nicely summarises research around SC and notes the somewhat turbulent position and confusion around culture and climate as constructs. It’s said that some consider surveys as being more suitable for climate compared to culture. In contrast, a counter argument is made that surveys are still regarded as suitable ways to study attitudes, values and perceptions about organisational practices and for providing a snapshot of the current state of safety.

In this paper it’s said that safety culture is an analytical concept not an empirical entity and thus, is a conceptual label to help describe the relationship between culture and safety. As discussed (p243-244), culture is therefore described as a frame of reference for meaning and action.

Note: I’ve had to skip or butcher a lot of the interesting context and findings from this paper. I highly recommend you read the paper if you can get it.

Results:

Before the accident

Regarding the SC survey data, it’s said that of all 20 items on the survey, only two items had a score below 4.5 out of 6 – highlighting overall positive scores on the survey. 7 of the items had a score of 5 out of 6, relating to adherence to procedures, prioritisation of safety, and organisational learning, said to be “key aspects of safety culture” (p245).

Of note also is that, positively, 95% of survey responses indicated that they consider risks involved before and after work – which, interestingly, were implicated in the following accident investigation as issues rather than as positively managed practices.

Overall, it’s said that these SC survey findings, in contrast to the resulting investigations, lead to the positive conclusion that “the culture of the Snorre Alpha organization is a culture of compliance and learning, sensitive of the risks involved and highly oriented towards safety” (p247).

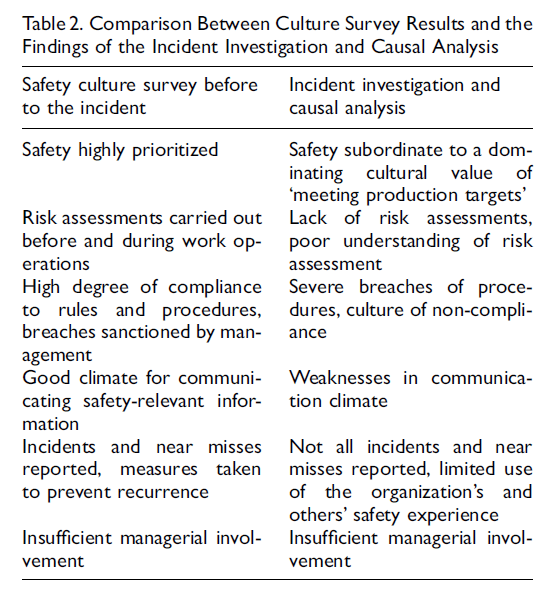

A comparison of findings is summarised in the figure below (taken from the paper).

After the accident

According to the investigation report, a range of deficiencies were found relating to compliance with procedures, lack of understanding of risk assessments, insufficient management involvement and more. Some of these directly contradicted the SC survey data at a time point before the accident.

Providing history of the Snorre platform, it’s noted it went through some major changes prior to the accident including a buy-out and integration into a new business, reorganisation, production pressures and a drive for efficiency.

A “can-do” culture at the platform was said to have led to hard work and creativity and improvisation to solve problems, leading to more ad hoc work with less room for formalised risk assessments and working to plan. This environment led to solving problems as they arose and not directing enough time and resources for long-term planning and maintenance.

Interestingly, it’s discussed that this ability to improvise and deal with unforeseen events without having to rely on plans or procedures was “essential for their ability to handle the blowout. In other words, the very same cultural traits that got them into trouble in the first place were the ones that got them out of trouble” (p248).

Based on the two post-incident reports is that several cultural traits were present that may have had adverse effects on safety. Notably, these descriptions of issues “differ quite dramatically from the picture painted through the culture survey” (p248).

This disparity between prior (positive) SC survey data versus post-incident reports was most evident with compliance to procedures and the use of risk assessments. The SC surveys did identify some traits that were later identified in the incident reports, namely lack of management involvement. However, this same issue was present across many other installations in the company and thus was a general problem and not specific to Snorre Alpha.

Further, while Snorre data did score in some respects lower than other installations, “these results provide little grounds for concluding that there is something ‘pathological’ about the Snorre Alpha organization” (p249).

The author then moves onto the question “why didn’t the survey identify more of the problems at Snorre Alpha?”. I’ve skipped over most of this section despite how interesting it is – I highly recommend just reading the paper. Nevertheless, a few things are discussed.

One is whether the time period between the SC survey and the incident could explain the disparity in findings. While this is seen as possible, it’s not believed to be overly credible since culture at Snorre wouldn’t have been expected to change so radically over that time period (1.5 year difference).

Is hindsight bias a strong factor in the disparity? This was seen as a quite inevitable conclusion because things are so obvious in hindsight because investigators after-the-fact “know where to look and what to look for” (p250). While it’s likely hindsight bias played a role, it’s argued that “this does not change the fact that the culture survey did not identify the problems” (p250).

The author then poses an interesting conundrum: a pessimistic view is that in some cases, proactive safety management may be impossible and only revealed through the “wisdom of hindsight” (p250). Nevertheless, the author believes this pessimistic view is a faulty interpretation, if highly reliable organising research, for instance, is indicative of the ability to proactively manage safety without waiting for bad things to happen.

Another reason and one which I’ve largely skipped over is the differences in the methods and perspectives through which the Snorre organisation was analysed between the prior SC surveys and post-incident investigation is likely to be a major determinant in the divergence.

In discussing the findings, it’s said that a limitation of surveys for SC is that they typically tap into perceived attitudes, values and perceptions and thus in regards to deeper cultural elements, “require that respondents should tell us more than they can know” (p252).

Further, it’s speculated that people may report on the way they feel they should feel or think regarding safety, rather than how they actually do feel or think; in other words and drawing on Guldenmund’s work, it draws more on peoples’ “espoused cognitions or attitudes”.

Therefore, gaining info on cultures requires a more “interactive assessment”, where insiders and outsiders “engage in a process of joint inquiry to uncover cultural assumptions” (p252). This emphasises taking the actor’s point of view rather than relying on the researchers’ point of view based on a priori categories.

The author doesn’t suggest abandoning surveys as they do have their place. However, SC assessments should utilise methods that provide valid descriptions of social processes and this may require ethnographies or at least based on ethnographic principles of fieldwork.

Regarding surveys, it’s said that they should be “more aimed at assessing properties of the practices involved and the context of these practices”. An example of what this looks like is provided.

Author: Stian Antonsen, 2009, Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5973.2009.00585.x

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/safety-culture-assessment-mission-impossible-ben-hutchinson