This explored the application of a framework for revealing and integrating S-I/S-II approaches in construction.

I can’t cover the methods themselves, including the Resilient Performance Enhancement Toolkit (RPET), so I suggest reading the full paper or Googling it.

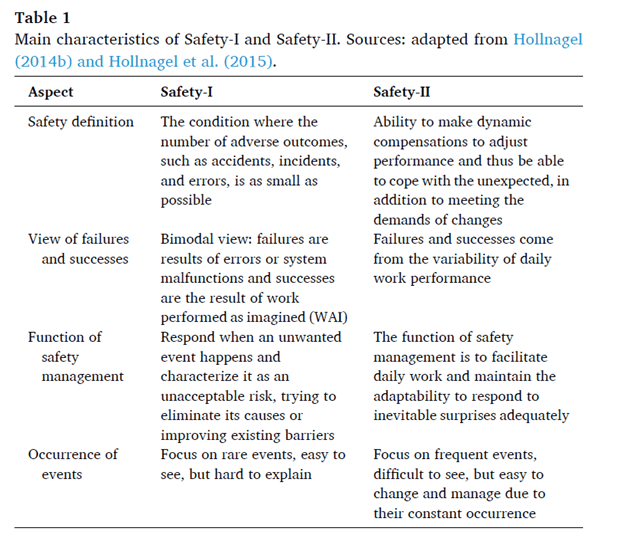

Providing context, they argue that “Safety-II is arguably more important for highly complex socio-technical systems, in which strict compliance with standardized operating procedures is not always possible nor sufficient for effective safety performance” (p1), and further argue Safety-II “grows in importance when the benefits from Safety-I achieve a plateau, to the point of Safety-I being itself a hindrance to further progress” (p1).

S-II is said to be relevant for construction, since construction has characteristics of complex adaptive systems, including the work environment and uncertainty and variability resulting from intensive use of subcontracted labour and aggressive contract arrangements.

A previous study highlighted numerous examples of S-II foci within a wider context of S-I in construction, where frontline workers adapted under conditions of resource scarcity and ambiguous information. Another paper found that “in three construction sites showed that, out of the ten tasks analyzed, nine were successfully completed, even though only four were executed close to WAI” (p2).

The authors highlight that S-II principles have largely only been applied to construction “as a lens for the retrospective analysis of existing practices” and there’s a need to apply it to daily work in construction.

A core element of S-II is understanding the gap between WAI and WAD. It’s said that S-I has more focus on ensuring alignment between WAI and WAD but “in complex adaptive systems, the front-line operation tends to be different from the operation planned by those responsible for the guidelines and procedures” (p2).

The gap may also be indicative of the resilient characteristics at the operational level. Wide gaps may indicate that management, who develop most process, “may be misaligned with the challenges and risks encountered on the shop floor and may be losing sight of how safety is created by those who perform the work” (p2)

Importantly, they highlight throughout the paper that “Safety-I and Safety-II are complementary rather than conflicting perspectives” (p2, emphasis added). Learning from normal work in no way precludes investigating and managing hazards and undesired events. As highlighted by other work, the same safety tools may be used under both S-I and S-II perspectives as it shifts mental models to different foci.

Further, “Safety-II is clearly not a license to let the burden for successful performance be on the shoulders of front-line workers” (p2). Rather, it’s about making sense of the system and organisational constraints, resources, goal conflicts etc. [** I’d also add, S-II isn’t about “throwing out the rules” as is often claimed.]

Whether you buy in to the adaptive views or not – this is still an interesting paper for revealing some gaps between WAI/WAD.

Results/Discussion

A lot of this paper was describing the methods themselves – I’ve skipped most of this. I’ll instead cover some key observations.

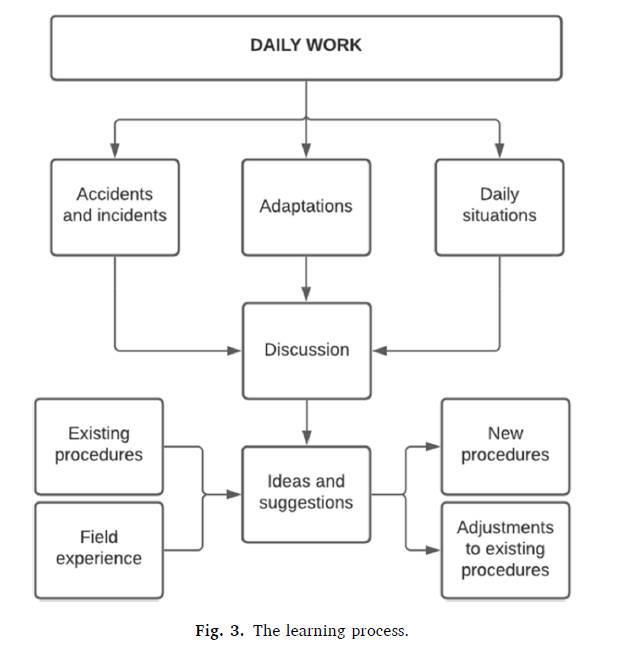

Three high-risk tasks observed (structural masonary, assembly of slab and concreting the slab) were seen to have a strong S-I orientation, such that safety management activities was largely concerned with finding hazards and setting barriers. Notably, there was “no formal mechanism for generating data and learning from everyday work” (p6).

Feedback on the employed methods was then provided. Operations and safety teams pointed out the feasibility of applying the concepts to reveal the reality of the workplace. It was said to have helped increase individual & team awareness of safety and generate new ideas for improving daily work.

Further, the operations team highlighted how the framework helped to increase communication between the team members and management. The foreman also informed that compliance to procedures improved and regular meetings to discuss normal work.

Procedures were discussed. They highlight how procedures represent essential practices to control risk and help to define and guide cognition and behaviour. They note “Even though the literature has documented the limitations and risk of over-standardization … procedures are still a safety practice that guides … performance, reducing or avoiding unnecessary risks” (p8).

Nevertheless, developing procedures and routines should involve the ops team as much as possible to avoid crafting a huge gap with WAI and excessive prescription that “is completely disconnected to WAD, even though the gap between the two is inevitable” (p8).

They further discuss that “resilient behaviour is based on feedback” (p8). Therefore, procedures can also act as a proactive communication channel to ensure that changes are properly presented and consulted with the operations team first for validation.

In wrapping up the paper, they remark that “the construction industry is still inserted in a highly reactive context accustomed to using only the traditional Safety-I approach” (p8). The framework covered in this paper [but not covered in my summary) doesn’t try to replace S-I with S-II but instead contemplate both approaches having a close relationship and purpose.

They note that large gaps with WAI/WAD wasn’t so much an issue with fairly stable conditions with high team agreement. Rather, great variance among practices with some safe and effective methods at one end and dangerous and ineffective at the other was problematic.

Importantly on the convergence of the concepts, having “adaptability to manage variability is welcome [but] not having a reference imposes unnecessary risk and reduces productivity because of incompatibility and lack of coordination between operation teams” (p8).

The authors observed features of daily work by drawing on this framework; including adaptations and variabilities in operational work, compressed execution time of slab assembly and changed equipment and other instances that increased risk of failure. In other cases adaptations were observed that were opportunities for improvement.

Notably, “Performance adjustments, which have always been successful in everyday situations, may result in accidents if they combine with other sources of variability under specific working condition, confirming that the causes of successful work outcomes are no different from failure outcomes” (p8).

For learning from the whole spectrum of work – they note that human performance variability provides the necessary adaptability to various situations. Thus, discovering the adaptations is just as important as finding the contributing factors to adverse events.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2022.105672

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:ugcPost:6925198317408727040?updateEntityUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afs_updateV2%3A%28urn%3Ali%3AugcPost%3A6925198317408727040%2CFEED_DETAIL%2CEMPTY%2CDEFAULT%2Cfalse%29