This discussion paper explored the conflicts between OHS management (OHSM) and operations management (OPM) from the perspectives of organisational logics. *** Note: I’ve skipped heaps of the points from the paper due to time/length, so consider below only a few key points.

It’s said that safety performance in OHSM certified companies has been subjected to some debate in the literature about the benefits, but generally the evidence suggests higher safety performance. Despite the benefits, “OHS management tend to end in a sidecar to the operations management (OM)” (p1).

The decoupling between OHSM and OPM has been referred to as the sidecar problem, where “OHS management is a separate activity organised in its own logic with little influence on operations” (p1).

That is, operations make decisions which influence their sphere but may have a negative influence on workers’ health and safety and conversely, OHSM make decisions that could negatively impact operations and not achieve their goals.

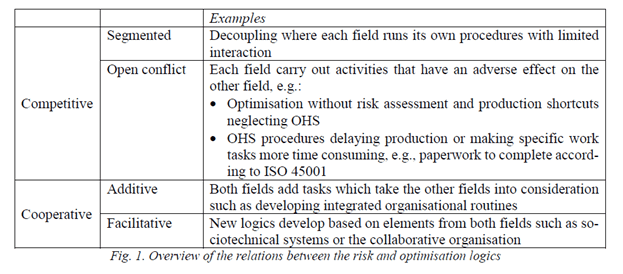

They use logics to frame the discussion. It’s said that professional fields are often dominated by one logic, but logics may “co-exist in ‘constellations of logic’ in a more or less competitive or cooperative manner” (p2).

This paper uses:

- a competitive constellation, where logics compete over resources and attention of actors and result in a gain of influence in one logic at the expense of another competing logic.

- A cooperative constellation, where logics are connected in a “zero-sum relationship”, existing relatively peacefully together. These constellations are facilitate or additive” facilitative when the existing two or more logics amplify each other (where they give an example of market logic and professional logics amplifying each other in the rise of pharmacies became independent businesses) or additive, where logics add to each other.

Two logics relevant for the paper are then discussed: 1) risk logic for OHS management, 2) optimisation logic for OPM.

Logic 1: Risk – the dominant logic for OHSM

OHSM is said to have its basis in a health-driven agenda, such as ensuring the health and safety of workers; what the authors termed the risk logic. This logic has been institutionalised over many years and various iterations of OHS legislation globally.

They argue that, in the European context at least, the primary basis of OHSM has been on risk assessment; which most facets of OHSM built on. However, in their view “the focus on risk does not necessarily create well-being among workers, and that some important features of working life such as social relations are difficult to catch with risk assessment” (p3).

Further, in small business, a focus on risk may be decoupled from the types of practice small businesses undertake and further “the attempt from legislators and OHS professionals to push small businesses to do risk assessment in order to improve the work environment may have detrimental effects” (p2).

One specific example where some evidence suggests OHSM and auditing may fall down is on effectively identifying, preventing and mitigating psychosocial issues at a deep level.

Logic 2: Optimisation – the dominant logic of OPM

In operations, the main focus is ensuring the best possible economic performance. Better optimisations, in the form of new technology or sequencing/organising of work results in higher performance.

Competitive and cooperative constellations

Below the authors summarise the interactions between logics, or lack thereof.

They argue that the dominant logics, and thus goals, of OHSM and OPM are different. OHS pursues goals that cost money and potentially restrict the most optimal ways to organise operations. They provide examples like machinery guarding and modifications (interlocks etc), restricting how chemicals are used, multiple rules around lifting or confined space entry etc.

Thus, “operations managers may consider OHS a hassle and try to avoid the involvement of OHS managers in the daily operations” (p5). Conversely, “operations managers pursue goals that the OHS managers may find incompatible with workers’ health” (p5). Examples may be shortcutting rules to speed up production, use of contracting payment systems that increase risk or purchasing and implementing new plant that may not be the safest available or have undergone full prior risk review.

They note that “studies of the OHS consequences of [production optimisations] show that they generally have a detrimental effect on workers’ health (Westgaard & Winkel 2011) and Brown et al. (2000) show that employees are torn between productivity and safety” (p5).

Nevertheless, producing products or services is the core reason an organisation exists and this is within the realm of the operations managers; therefore operations managers “tend to have the upper hand in relation to the OHS managers” (p5). OHS Managers are said to have argued [struggled?] to be accepted into operational decision making processes, using a logic that good safety also tends to be good business.

Thus, OHSM becomes a sidecar function – put to the side-line and “shouting to top management and operations managers – ‘we are not only a cost but also contributing to the economic performance’” (p5). They say it’s uncertain whether this strategy works. An Operations Manager may face the following conundrum: OHS investments by themselves may improve economic surplus in some way, but the investments overall may be considered to limit operational output and thereby the optimisation logics.

Interestingly, they argue that OHSM may have silo’d itself. OHS Managers completing safety-centric activities like making and documenting risk assessments, checking PPE, investigating and reporting incidents—all within their own dominant logics [and what we may call safety work as per Rae & Provan, rather than safety of work]—may have limited influence on the core of operations.

[That is, safety people may largely be creating, changing and influencing their own segmented safety work and outputs more than deeply influencing operations and they may have themselves created this segmentation, aggravated by certifications and the like.]

This segmentation “therefore places the OHS managers in the sidecar” (p5).

The authors then discuss the interactions of operations, OHS and worker involvement – I’ve skipped a lot of this. They highlight that OM that involves workers is key to high productivity; a process where managers increasingly lose direct control of workers and thereby become more dependent on worker engagement as they recraft their own environments and tasks for optimisation. Likewise for OHSM, where focus is shifted somewhat from just risk to the positive well-being of workers.

They argue that simply avoiding physical risks and disease isn’t sufficient but also necessary to drive positive goals of well-being; likewise with high OM performance, where it’s necessary to optimise the conditions and organisational factors to drive employee well-being such as autonomy and collaboration.

More collaboration between the functions is also critical. They highlight research suggesting that the best performing manufacturing companies in that sample were the ones utilising joint management systems (JMS). However, half of the manufacturing companies in that sample only had a focus on systematic OM, systematic OHS, or had systematic elements of both, but were equalling low performing in both.

Greater integration in both, such as via JMS, also enables a call to arms for socio-technical perspectives of organisations in integrating design of the environment for both high productivity and well-being of workers.

Further, “rethinking the production set up and the workers’ role, possibilities open towards a facilitative cooperation between the two dominant logics, where they not only support each other in fulfilling each logic’s objective, but also open towards synergy between the logics” (p6).

In wrapping up their arguments, they note that via additive or facilitative logics “there may in fact be a chance for “the twain to meet” (p6). Notably, this may result when “professionals in each field develop their knowledge and acceptance of the other field, but also the development in technology and organisational forms that put pressure on their own field to change. Operations managers from detailed planning and control” (p6).

For Operations Managers, this means not just the focus on planning and control of production but to coaching and integrating of worker well-being in the production workflows. For OHS Managers, “it is important to move from the sidecar role to take co-responsibility for development of performance” (p7).

[My thoughts: I’d further add that I think operations managers often have a better sense of safety than OHS professionals have for operations. E.g. supervisors in construction could “do safety” more readily in my opinion than safety professionals “do production”. Hence, I think the safety profession could get more buy-in and respect in decision-making by having a deeper understanding of production methodologies, pressures, trade-offs, planning, design etc. Help solve their problems rather than adding to the problems.]

Authors: Hasle, P., Madsen, C. U., Hansen, D., & Maalouf, M. M. (2019). Paper presented at 6th International EUROMA Sustainable Operations and Supply Chains Forum, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Study link: https://vbn.aau.dk/en/publications/occupational-health-and-safety-management-and-operations-manageme

My site with more reviews: https://safety177496371.wordpress.com

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:ugcPost:6927007785188548608?updateEntityUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afs_updateV2%3A%28urn%3Ali%3AugcPost%3A6927007785188548608%2CFEED_DETAIL%2CEMPTY%2CDEFAULT%2Cfalse%29