This was a brief theory paper describing a new method for scoring the strength of corrective actions with the intention of determining the influence on broader systems change – called the systems change hierarchy (SCH).

This summary/paper will be clearer to you if you have a squiz at the Action Hierarchy (AH) methodology from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, as the SCH was developed based on perceived limitations of the AH.

Nicely, they start with a classic quote from James Reason, which provides context for their central arguments:

They argue that from a conventional perspective, “strong” recommendations are those that rely less on people’s actions and memory and more on engineering and workplace design – with more a focus on active failures (based on the AH methodology). These are undoubtedly good solutions in many cases.

They give an example of a patient’s oxygen mask incorrectly connected to an air flowmeter rather than an oxygen flowmeter under time and resource pressure. The contemporary “strong” corrective action would be to redesign the fittings so they cannot be intermixed. This makes a lot of sense and may involve forcing functions (design factors which prevent unintended or undesirable actions or outcomes or in a particular sequence).

This change would also exist elsewhere in the hospital, so sharing the idea will help to change the issue “system-wide” but this doesn’t necessarily make it a “systems fix”. In part, this is because in solving the local active issues, the methodologies may not strongly enough emphasise system change and the latent factors that contributed to the variability; in this case, time pressure and limited resources etc.

Conversely, they argue that “many systems changes would likely be considered ‘weaker’ actions using the AH’s standards and discarded for stronger local fixes” (p439). Again, not a bad thing solving local issues with better design but it may omit broad fixes of latent issues that are less visible.

That is, changing the design to prevent cross-connection between air and O2 attachments is undoubtedly a strong corrective action but may “have a nominal impact on the organization’s overall patient harm rate, because it does not address the underlying latent conditions that promoted the active failure (i.e. hooking the tube to the wrong flowmeter)” (p440).

Next, they ask the rhetorical question “What does it matter?”, since the new equipment design prevents the misconnection between the air and O2.

They say that this is true, but “we have not addressed the latent conditions [and thus] other seemingly arbitrary active failures (i.e. errors) will emerge, such as not fully turning on the gas, not noticing the tubing is loose or that the patient has moved the mask, misadministering an aerosol-based medication” (p440) and several other plausible failure modes.

Further, latent conditions can manifest in other ways, noting that “efforts to prevent the repetition of specific active [failures] will only have a limited impact on the safety of the system as a whole” and “At worst, they [are] merely better ways of securing a particular stable door once its occupant has bolted” (p440).

Hence the connection with swatting mosquitoes (waiting for active failures and addressing them ad hoc) or implementing major systems changes (not just systems fixes) that addresses the common underlying conditions (draining the swamp).

These conditions may result in incrementally improving safety one event at a time – which is “necessary, yet insufficient, for improving safety” (p438).

First, they provide a definition of systems change before offering their proposed SCH methodology. Here they define it as “an intentional process designed to alter the performance of a system by shifting and realigning the form and function of a targeted element’s interactions with other elements in the system” (p440).

Systems elements in this context can be conceptualised as:

- Meta-level changes: political, regulatory or societal level

- Macro-level changes: organisational or healthcare system

- Meso-level changes: department or unit level

- Micro-level changes: group or individual level

Results

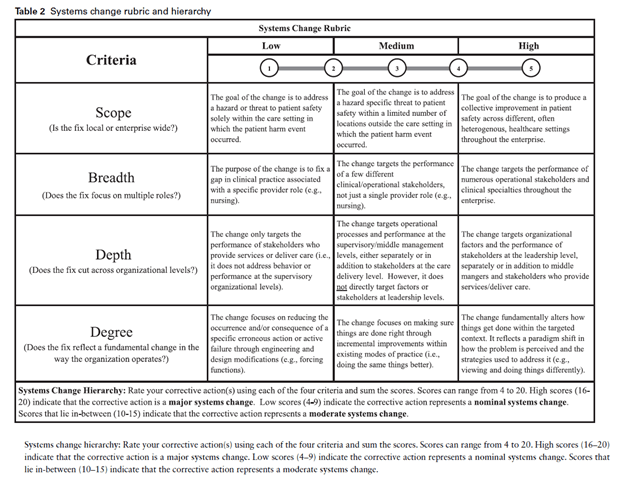

The below image of the SCH highlights the methodology; consisting of four criteria.

1. Scope – is fix local or enterprise wide?

2. Breadth – does the change target more than one clinical role?

3. Depth – does the fix cut across multiple levels of the organisation?

4. Degree – does the fix reflect a fundamental shift in the way the organisation operates?

These factors then result in scores. For instance a high overall score across all dimensions (16-20) would be considered a major systems change seeking to “widely transform latent conditions across all system levels”.

A corrective action receiving a low overall score (4-9) would be considered a “nominal systems change” that “likely addresses active failures at the micro-level” (p441). A moderate systems change (score 10-15) would likely target latent failures across limited meso-levels and adjusting/tweaking the same things that have always been done but doing them a little better.

They then apply this SCH rubric to that air/o2 incident from earlier (which I’ve skipped here). However one thing they note is that compared between the existing AH methodology and their proposed rubric, there appears to be a “rank reversal” between the corrective actions coming from both approaches.

In particular, a better emphasis on something like leadership and management structures/resources to alleviate staffing pressures etc. may come as a result of looking broader.

In any case, they argue for a holistic approach involving different perspective and not simply the adoption of this tool or any other myopically.

Notably they argue that “A holistic approach … includes the implementation of several types of corrective actions: strong fixes that address active failures at the micro-systems level, intermediate strength actions that focus on latent failures by ‘doing things better’ at the meso-level and major systems changes at the macro-level that fundamentally alter latent conditions throughout the enterprise” (p442).

In contrast, they state that many recommendations following incident investigations include “neither stronger fixes (i.e. AH actions) nor major systems changes (i.e. SCH actions)” (p442). Rather, existing investigations in this domain seem to focus more on weaker-strength actions at the micro-level, like warnings, or inter-mediate actions at the meso-level, like training.

They argue one existing constraining factor for improvements in patient safety [*** but this probably applies elsewhere], is a focus on continual improvement. Continual improvement, like “doing the same things better” (p442), while important, may bias local fixes at the expense of “major systems changes that fundamentally transform an organization’s approach to ameliorating latent conditions” (p443).

In concluding, they state that a “considerable emphasis has been placed on corrective actions that are stronger than the training and policy changes that commonly emerge from investigations of patient harm events” and while this is critically important, it may have “detracted from healthcare systems’ pursuit of major systems changes that address the latent conditions that consistently underlie patient harm” (p443).

Personally, I think their arguments also have some applicability to the hierarchy of control methodology.

Authors: Wood, L. J., & Wiegmann, D. A. (2020). International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 32(7), 438-444.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa068

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:ugcPost:6937155238910971904?updateEntityUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afs_updateV2%3A%28urn%3Ali%3AugcPost%3A6937155238910971904%2CFEED_DETAIL%2CEMPTY%2CDEFAULT%2Cfalse%29

One thought on “Beyond the corrective action hierarchy: A systems approach to organizational change”