One of two papers exploring the nature of cognitive biases and heuristics in medical decisions. These papers have some interesting points that are relevant outside of medicine. They’re also open access, so you can read the full papers yourself.

I’ll be posting a few studies in the coming period on debiasing, decision-making and similar themes.

The authors also briefly cover the origins of bias and some debiasing methods. Note that:

- Debiasing in this context has some pretty inconsistent and shaky evidence, recognised by the authors

- “Bias” isn’t meant to indicate a weakness or problem with people. It simply means “systematic errors” and/or “predictable deviations” from an expected outcome. That is, a lot of biases are actually intentional (from an evolutionary perspective) and useful (a bias towards eliminating visual noise when driving your car so you can focus on actually driving, biases that allow rapid decision-making when interacting with the world etc).

- This work pre-dates the focus on noise from Kahneman, so it mostly focuses on bias and not noise.

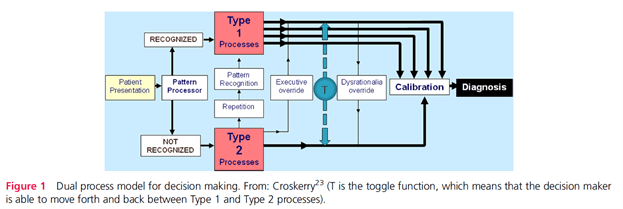

They draw on the Dual Process Theory (DPT) of decision making. Namely type 1 and type 2 processes [* the authors didn’t discuss and nor am I covering the criticisms to the dual process model…that’s another whole series of posts.]

Paper 1 looks at the background on decision-making whereas paper 2 focuses more on specific debiasing strategies.

Type 1:

- These are the “fast … and usually effective” intuitive processing domains.

- This is characterised by heuristics or “short-cuts, abbreviated ways of thinking, maxims, ‘seen this many times before’, ways of thinking” (p58). Heuristics are an adaptive mechanism that saves us time and effort in daily decisions. Apparently, a rule of thumb is ~95% of daily decisions being handled by type 1 heuristics.

Type 2:

- The “fairly reliable, safe and effective, but slow and resource intensive” processing domains.

- It’s slower, deliberate, rule-based and characterised by conscious control

For the interactions between the two, it’s said that:

- Bias, that is, predictable deviations from rationality or expected outcomes, are more likely to occur under type 1 processing (but not exclusively)

- There are over a hundred identified biases and around a dozen of these are affective biases, meaning they influence or are influenced by our feelings

- Issues in clinical reasoning rather than lack of knowledge may underlie more cognitive diagnostic errors

- Repetitive processing under type 2 processes might allow processing in type 1; “the basis of skill acquisition” (p60)

- Biases that negatively impact judgements can, to varying degrees, be overridden with explicit effort at reasoning. That is, “Type 2 processes can perform an executive override function—which is key to debiasing” (p62)

- The decision maker under the proposed model below can toggle back and forth between the two processing types

- it’s argued that many biases have multiple determinants (experience, pattern matching, environmental factors, fatigue etc.) and thus unlikely that “there is a ‘one-to-one mapping of causes to bias or of bias to cure” (p60)

- increased intelligence does not protect against biases

Notably, the below model doesn’t imply that a single reasoning mode accounts for diagnostic errors, nor one is preferable over the other. More likely is that decisions involve varying degrees of interactive combinations between the modes. Further, a high degree of type 1 processing is some circumstances is essential and lifesaving, whereas in other situations more deliberate rationalistic and reflective processing is needed.

Type 1 processing has been further categorised based on their origins.

- Hard-wired processes. Naturally selected in the Darwinian sense in our evolutionary past. This includes “innate” heuristics that might induce biases like anchoring, adjustment, representativeness, availability, search satisficing, overconfidence etc.

- Emotion or affective processes. Also evolutionary adaptations (hardwired) and grouped into six major categories: happiness, sadness, fear, surprise, anger and disgust. They note that fear of snakes is universally present in all cultures; but may also be socially constructed via learning, or combinations of both.

- Processes that become embedded in our cognitive and behavioural repertoires via overlearning. This includes cultural and social habits but also via specific knowledge domains.

- Processes developing through implicit learning. This includes both deliberate explicit learning via school and the like and also implicit learning via skills, perceptions, attitudes, behaviour. They argue that implicit learning allows us to detect and appreciate complex relationships in the world but without necessarily being able to articulate that understanding. Thus, some biases develop unconsciously.

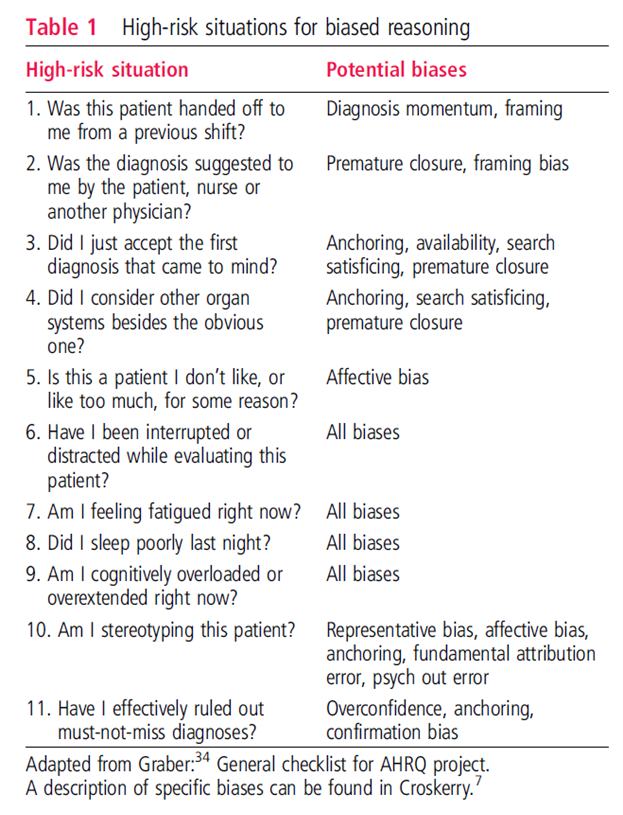

Particular situations are more conducive to bias. This includes fatigue, sleep deprivation and cognitive overload predispose decision makers towards type 1 processes.

Debiasing primer

A technique in debiasing are forcing strategies. One forcing strategy in diagnosis is ruling out the worst case scenario; helping to avoid the worst stuff being missed. Another forcing strategy is always placing car keys in a specific place so we don’t lose them.

Another simple, protective forcing strategy is the maxim “measure twice, cut once”.

Other research has proposed an algorithmic approach to debiasing (with a schematic shown in the full paper). It involves several successive steps from awareness, to motivation and applying a strategy.

For awareness of bias – sometimes just being aware isn’t enough. They note that vivid and emotionally laden experiences may need to occur to precipitate cognitive change.

Use of an algorithmic approach mat require:

- An awareness of the rules, procedures and strategies needed to overcome bias

- Have the ability to detect the need for bias override

- Be cognitively capable of decoupling from the bias.

On this, “a critical feature of debiasing is the ability to suppress automatic responses in the intuitive mode by decoupling from it” (p63). This is shown in the first image above as the executive override function.

The decision maker must be able to use situational cues to detect the need to override a heuristic response, and then sustain the inhibition while analysing alternative solutions [** naturalistic decision making would also have an alternative lens on this].

Such solutions need to have been learnt and previously stored in memory and thus, “Debiasing involves having the appropriate knowledge of solutions and strategic rules to substitute for a heuristic response as well as the thinking dispositions that are able to trigger overrides of Type 1 (heuristic) processing” (p63).

In the follow up paper, the authors then cover some general and specific debiasing strategies.

Authors: Croskerry, P., Singhal, G., & Mamede, S. (2013). Cognitive debiasing 1: origins of bias and theory of debiasing. BMJ quality & safety, 22(Suppl 2), ii58-ii64.

Study link: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001712

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/cognitive-debiasing-1-origins-bias-theory-ben-hutchinson