Another earlier paper (2004) paper from James Reason, talking about the progression of active and latent conditions related to a fatal medication event. From this he discusses enhancing “error wisdom” to buttress organisational safety approaches.

Note – I think some of the terminology and ideas are a bit dated. However, if you apply a modern lens to his ideas then I think most of them align really well (e.g. “error wisdom” is related to enhancing non-technical skills and use of heuristics and pattern matching etc.).

Also, Jim relates the incident progression via the Swiss Cheese metaphor. If you overlook the rather linear progression as presented in the paper as more about non-liner interactivity, then I think it aligns well with contemporary systems lenses (and if you’re getting stuck on Swiss Cheese or his use of “error” rather than better descriptors of performance, then I think you’re missing the point anyway).

First, Jim provides some background on organisational safety. He notes that “Complex, well defended, high technology systems are subject to rare but usually catastrophic organisational accidents in which a variety of contributing factors combine to breach the many barriers and safeguards” (p28).

Healthcare is said to be a bit unusual in the scope of hazardous domains. Compared to petrochemical or nuclear plants, which tend to have well understood and specified operating parameters, hospitals are largely human-driven enterprises. This includes a wide diversity of operations, equipment, emergencies, tasks, skills, uncertainty and pressures.

Whereas it would be difficult for an individual pilot to crash a large commercial airline without considerable planning and opportunity, “in many healthcare activities serious harm is but a few unguarded moments away” (p28).

Chemical plants and the like rely a great deal on automated and technological devices, whereas in healthcare (and likely other human-driven domains like forestry, fishing), safety is driven largely by people on the fly.

Jim argues that in some organisational accidents, more purposeful and developed error wisdom capabilities may have thwarted the events.

He provides an example of how system defences failed and led to the death of a young patient. The patient died after receiving an intrathecal injection of vincristine; toxic in this application and meant to be injected intravenously.

A large number of contributing factors were listed for this event. Some include:

- Protocols that separated intrathecal and intravenous drugs to administration on different days were amended so that both types of drugs were then given on the same day; saving patients two visits to the hospital

- The order of drugs (day 1 intrathecal) and day 2 (intravenous) was reversed

- The pharmacy required both types of drugs to have separate labelling and packaging but on this occasion, the pharmacy allowed both drugs to be delivered together in the same bag for the convenience of the ward and patient

- Protocols required these drugs to be administered on separate days and never on the same trolley; but these instructions evolved to suit local requirements

- The same prescription form was used for both types of drugs despite the toxicity of mixing the administration route. Handwritten initials was the only thing that distinguished their distinctive routes rather than different coloured forms etc.

- Inconsistent font sizes between the drug name and dosage (9 point) versus the warning of route of administration (7 point) de-emphasised the critical information

- Although there were different coloured syringes, there were also many similarities which “offered little in the way of discriminatory cues” (p30)

- + heaps more factors.

Jim then argues that organisational accidents arise from the concatenation of several factors across various levels; in combination these factors combine with local triggers and allow unexpected pathways of performance. They involve active failures and latent conditions – the latter involving defensive gaps, weaknesses or absences that “are unwittingly created as the result of earlier decisions made by the designers, builders, regulators, and managers of the system” (p29).

Because these gaps exist in all hazardous systems and not all of them can be foreseen, it’s people that provide the necessary adjustments for ensuring safe and reliable performance and managing unexpected emergency situations.

He notes the importance of thinking beyond people as hazards. Active failures rarely arise solely from psychological processes or negligence. Rather, they result more often from error provoking conditions within the work system.

It’s noted that inadvertent intrathecal injection of vincristine was well-known and happened many times even in prestigious hospitals. He argues that because these previous events “involved different healthcare professionals performing the same procedure clearly indicates that the administration of vincristine is a powerful error trap” (p29).

That is, “When a similar set of conditions repeatedly provokes the same kind of error in different people it is clear that we are dealing with an error prone situation rather than with error prone, careless, or incompetent individuals” (p29).

While the hospital had a variety of controls, barriers and safeguards to prevent intrathecal injection of vincristine, these failed in many ways and at many levels.

He argues that at just 20 minutes before the drugs were fatally administered, the “large majority of the ingredients for the subsequent tragedy were in place” (p29).

The event happened during a normally quiet period and some critical staff were not present that day. The patient and his grandmother had arrived unannounced and not scheduled for that particular time. The treatment was given by a senior house officer (SHO) who wanted to give the injection for the experience (inexperienced in that area). The SHO was supervised by a specialist registrar (SpR), but confusion existed around the role of the SpR for supervision.

Both drugs arrived at the same time in the same package. The SpR handed the SHO the drugs and read out the patient’s name, the drug and the dose but he didn’t read out the route of administration. He also didn’t check the treatment regimen nor how it should be delivered. He also failed to appreciate the SHO’s query on administering vincristine intrathecally.

Jim argues that the SpR’s “actions were entirely consistent with his interpretation of a situation that had been thrust upon him, which he had unwisely accepted and for which he was professionally unprepared” (p30). Other research shows that people see what they expect to see, so the SpR wasn’t expecting incompatible drugs to be administered at the same time.

Nor would he assume that all of the existing protocols and safeguards would reasonably fail at the same time in such a way to allow the drugs to be misadministered.

Thus, “Given these false assumptions, it would have seemed superfluous to supply information about the route of administration. It would be like handing someone a full plate of soup and saying ‘‘use a spoon’’ (p30, emphasis added).

Jim then moves into error wisdom. He notes that no matter how assiduously organisations manage critical controls, all of the latent pathogens can never be eliminated. Therefore we need to also rely on the “last line of defence” via people.

A study on surgical teams is highlighted. This study found that wide performance variability (errors) was a relatively frequent occurrence. However the best performing teams were not the teams with the least variability but the most capable of compensating and adjusting for the variability.

Jim notes that while these surgical teams were extremely experienced and that we can’t directly transplant that experience into junior staff (technical skills, which takes time), we can improve their non-technical skills that underpin error wisdom.

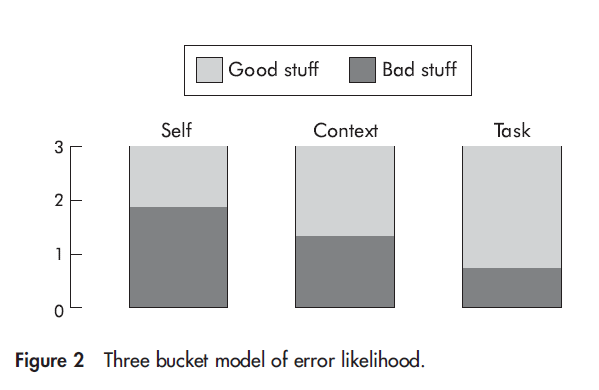

Jim then discusses some aspects of error wisdom that may allow people to be alert to particular signals and warning signs. He uses a “3 bucket” metaphor.

The first bucket, self, relates to the current state of the individuals. This includes lack of knowledge, fatigue, negative life events etc. The context bucket includes things like distractions, interruptions, shift handovers, harassment, lack of time, lack of necessary resources, unserviceable equipment. Task includes the actual things people are doing. This can include the task sequence of steps, pace, visibility and feedback etc. Jim says task is sensitive to “omission errors”.

People are very good at making rapid intuitive ordinal ratings of situation aspects and therefore with some “inexpensive instruction on error provoking conditions”, frontline staff can acquire the mental skills necessary for roughly identifying and adjusting to “error risk”.

It’s then discussed how the 3 bucket metaphor can help to promote excellence:

- Accept that errors can and will occur

- Assess the local bad stuff before embarking on a task

- Have contingencies ready to deal with anticipated problems

- Have structures in place for people to seek more qualified assistance and verification

- Don’t let professional courtesy get in the way of double-checking [* sometimes called “trust but check”]

- Appreciate that the path to adverse incidents is paved with false assumptions

Unfortunately, for a paper focusing on building better mental and structural capabilities for people to maintain performance in the face of system failures, I think the error wisdom part of the paper was the least developed argument. Instead of talking about these capabilities and non-technical skill development etc. in depth, the paper focused more on the dubiously useful 3 bucket metaphor.

But, whatever.

In any case, I think Jim makes some important points around how safety is maintained by people rather than technology (it’s people that design, install, use, maintain, upgrade and decommission the technology).

Further, an effective part of maintaining reliable performance is not just our formalised systems but enhancing the informal and non-technical skills of people and the environment that they operate in.

Author: Reason, J. (2004). BMJ Quality & Safety, 13(suppl 2), ii28-ii33.

Study link: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2003.009548

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:ugcPost:6980278049216880640?updateEntityUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afs_updateV2%3A%28urn%3Ali%3AugcPost%3A6980278049216880640%2CFEED_DETAIL%2CEMPTY%2CDEFAULT%2Cfalse%29

One thought on “Beyond the organisational accident: the need for ‘‘error wisdom’’ on the frontline”