A really interesting study which explored the relationship between cultural factors and organisational failures.

58 studies were included in the review.

Way too much to cover in this paper – I recommend you grab the full paper if it interests you. Also, for those critical of “safety culture”, this paper more explores how research has framed cultural items in the context of accidents; so the findings are interesting for those for or against SC as distinct from org cultures, in my view.

That is, you may critically question whether some/many of the factors shown in the results may be cultural in origin. But that’s what I think is interesting about this paper in that you can see how and what factors get associated as cultural artefacts across a range of accidents.

Providing background it’s stated that:

- Previous research on culture and accidents has coalesced into two paradigms: safety culture (SC) and ethical culture (EC); these examine how management of risk and ethics shape attitudes and practices

- However, they note that curiously despite the frequent discussion of cultures, existing models of SC/EC haven’t substantially linked the concepts to largescale failures

- Org culture “provides the rather stable and shared system of values, beliefs, and assumptions which provides approved modes of thought and behaviour, is resistant to change, and maintained through social interaction” (p458)

- Schein further stratified culture by levels of meaning, where the deepest level comprises underlying and pervasive assumptions that are tacitly accepted. The intermediate level is around what people espouse to believe; the most superficial level is around visible or audible patterns of behaviour and artefacts

- Division exists around whether organisations should be considered “as cultures”, or “something an organisation has”

- Links between cultural factors and safety are briefly covered. For instance, latent conditions within organisations “persist undetected and are a product of culture, as well as management decisions, and organisational processes. However, only culture is ubiquitous enough to influence all aspects of defence. Culture “can not only open gaps and weaknesses but also—and most importantly—it can allow them to remain uncorrected” (p459)

- Limitations in existing models of SC/EC exist. For instance, survey-based studies on cultural factors have linked ‘what’ cultural dimensions but not necessarily ‘how’.

Results

Based on the analysis of 58 studies, it was found that:

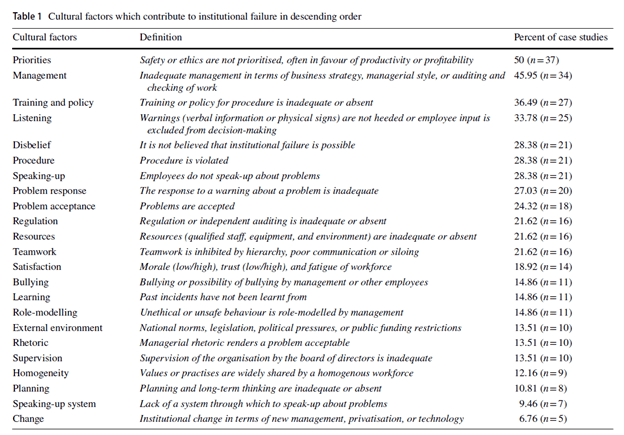

- 23 common factors and a common sequential pattern were linked to SC/EC across the sample of 58 studies

- Two distinctions were observed on how cultural factors are linked to failures. One is how “culture is described as causing practices that develop into institutional failure (e.g. poor prioritisation, ineffective management, inadequate training)” (p457)

- Another distinction is that research also linked culture to failure as problems of correction, e.g. “how people, in most cases, had the opportunity to correct a problem and avert failure, but did not take appropriate action (e.g. listening and responding to employee concerns)” (p457)

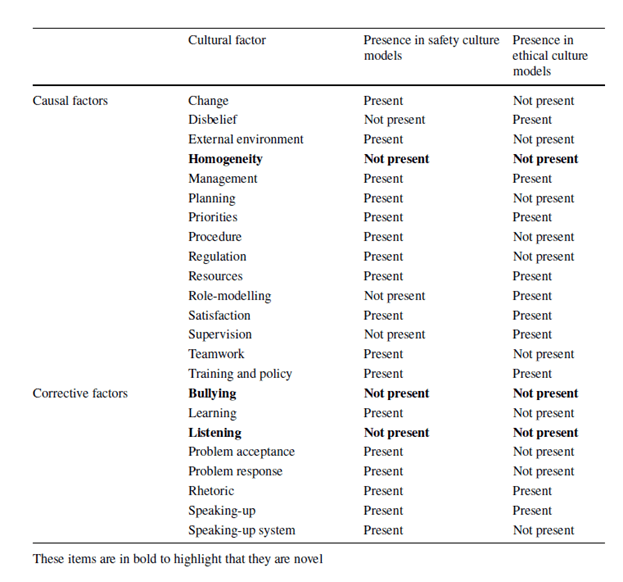

- Most of the cultural factors identified across the research sample were consistent with the survey-based models of SC and EC [** this doesn’t mean survey methods are more valid, but that there’s overlap between the factors identified as being causal/contributory to failure in a particular study and those items identified via survey]

- Failures relating to safety and ethics largely involved the same causal and corrective factors of culture, but some differences were observed, e.g. loss of human life was more often preceded by the cultural factor “management not listening to warnings”. A few other factors were highlighted.

A list of the factors are below.

The most commonly observed cultural factor was a problem in how priorities were ranked in the organisation – where production was prioritised. Examples include the Enron failure, and how less productive employees were culled every year and thereby created a cut-throat environment for employees that normalised accounting fraud.

In only a few studies were the preconditions for this factor covered. In the few cases where info was available, a failure to prioritise safety and ethics was largely the result of forces outside of the company’s control (societal or national norms, neoliberalism etc.)

“Management” was another common factor. It involved leadership style and personality, like the CEO being distant and unavailable, but more often involved managers and supervisors who didn’t discharge due diligence around the state of safety, resources and equipment onsite.

Overly generous reward structures was also prevalent and encouraged unethical behaviour. They note that the “large role attributed management must be considered in relation to inadequate board supervision which was less frequently cited” (p465).

“Training and policy” was another common factor. This related to the content or availability of information about company processes etc. Overly proscriptive process was seen to deter employees from departing from process “even when a situation demanded it”, such as identified in a fatal aviation accident where departing from process would have been a safer option.

Policy was also observed to “give license to unethical practise through vagueness” and “[w]hen people are not sure what to do, unethical behaviour may flourish as aggressive individuals pursue what they believe to be acceptable” (p465).

“Change” was the least cited contributing factor to failure. Change contributed to failure when it clashed with or weakened existing cultures, norms, practices etc.

“Speaking-up system and bullying” was also covered. Observed was that having a suitable medium wasn’t the most important factor in employees speaking up. Rather, the research more commonly attributed employee silence to fear of victimisation of bullying and retaliation.

That is, rarely was a lack of a communication or whistleblowing system present in failure but rather people felt unable to use those systems.

Next the authors compared the EC/SC models against their extracted data. Two distinctions of how culture was framed across the research was:

1) culture as problematic values and practices, which included 15 of the 23 identified factors. These factors (see images in this post) are said to create the preconditions to failure,

2) Issues of corrective culture, which manifest as “problems dealing with problems’. This accounted for 8 of the 23 factors (e.g. bullying, problem acceptance, speaking-up. Problems of corrective culture, unlike culture as problems as in category 1, “do not advance the development of a failure. Instead, they represent missed opportunities to address a problem and potentially avert failure” (p466).

The authors also note that while existing models of SC/EC and cultural surveys largely overlap in their factors, three cultural factors – listening, bullying and homogeneity – were said to be novel factors identified in this study.

Homogeneity is the lack of diversity and “was predominantly fostered through recruitment and promotion practises which rewarded unethical behaviour with a sense of belonging (Crawford et al. 2017) or (continued) employment” (p468).

Homogeneity has been studied as a source of cultural strength, and shown to have positive effects in job satisfaction, stress and better financial performance when directed at the company board. However, this factor has hitherto not being as well canvassed in the context of organisational failure.

It’s also stated that listening, a common factor in failure, is not typically measured via survey-based studies in SC/EC. This is a noteworthy finding because “a failure to listen to signs or information about problems is mentioned by a third of case studies them. Others use the term ‘deaf effect’ to understand when organisations persist with projects despite reports of trouble” (p467).

Further, other work suggests that listening to whistle-blowers creates a mutually-reinforcing cycle that benefits org. learning, whereas “organisational disregard” creates a norm of silence.

Other challenges include how people, such as managers, are more likely to agree with info that supports rather than challenges the organisation’s goals.

Not listening/not heeding info was an outcome of culture in two ways. First, the info received could challenge the receiver’s taken-for-granted assumptions about the world as a cultural member – this misalignment between info and cognitive frame termed an ‘epistemic blindspot’.

The second outcome of culture was “because the information, whilst decoded ‘correctly’ in terms of intent and content, conflicted with competing cultural values and demands. These include a pressure to maintain performance levels … and having to manage with limited resources” (p468).

Bullying is another factor not typically part of models of SC/EC. Bullying deterred employees from speaking up about organisational problems and “Bullying had pragmatic qualities somewhat similar to gossip: it was a form of social control directed at someone perceived to have transgressed the rules, which seemed to reinforce the group’s normative boundaries of right and wrong” (p468).

The authors then explore cultural factors by the failure type (human losses of life, enviro damage etc.). I’ve skipped this section.

Discussion

Overall, all but one cultural factor occurred at least once in a failure of safety and ethics, indicating that failures “stem from a common set of values and practises” (p471).

Some discrepancies existed. Ethical failures more often had issues of corrective culture “perhaps reflecting that they involve greater obfuscation than safety failures, although safety failures did involve more problems of listening and learning” (p471).

Organisations prioritising productivity over ethics and safety was the most common theme across accidents. Such goal conflicts are driven by capitalism, privatisation and permissive legislation. They note that “Perhaps, as Rasmussen (1997) suggests, organisations systematically move towards greater efficiency” (p470).

Recognising warning signs is obfuscated by issues of corrective culture, which prevented the timely and effective resolution of issues.

They argue that causal culture “pushes an organisation toward failure, creating disequilibrium. Corrective culture pulls an organisation back from failure, maintaining equilibrium” (p471).

Another noteworthy point is that while many accidents described failures as arising from sequential set of factors, culture was treated as interacting. Thus, “Dimensions of culture do not exist in isolation from one another: problems in one dimension can produce problems in other dimensions” (p471).

Authors: Hald, E. J., Gillespie, A., & Reader, T. W. (2021). Journal of Business Ethics, 174(2), 457-483.

Study link: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10551-020-04620-3

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/causal-corrective-organisational-culture-systematic-ben-hutchinson