This paper explored the evidence around the types of biases and noise present in incident investigations and then some proposed solutions.

It’s said that the investigation literature doesn’t comprehensively address this topic.

I’ve had to skip large parts of this, so check out the full paper.

Bias is “the systematic deviation from evidence-based, objective judgment” and “All people, including experts, are susceptible to making biased decisions” (p1). People are largely unaware how and when bias affects their judgements.

Bias isn’t random error but systematic deviation. The author gives an example of a scale that always shows weight 10lbs in excess of the person’s true weight – this is bias [* noise would be if the scales gave a varying range of weight values.]

Bias isn’t always bad; nor does it always lead to wrong conclusions, but rather bias skews perceptions and judgements towards particular directions counter to what the evidence (in theory) would suggest, or in the direction of evidence but more or less often than what is appropriate.

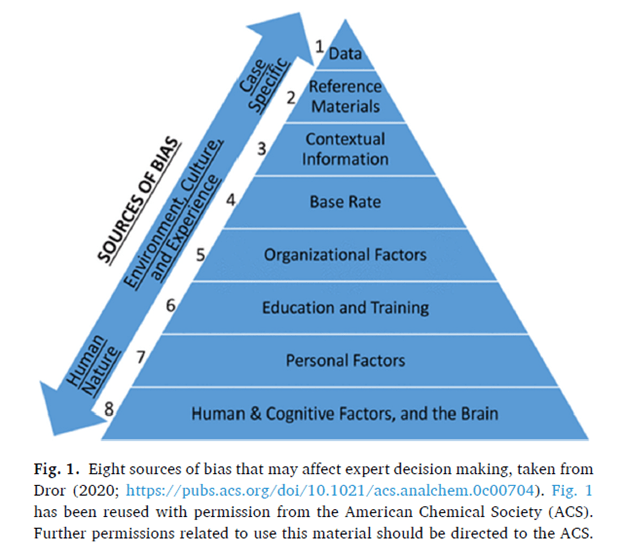

Various sources of bias exist, shown in the image below. It’s said workplace info is often ambiguous and incomplete and may be conducive to use of heuristics and influence of bias. Hence, the “malleability of what a piece of information means in an investigation fundamentally challenges the efficacy of the mantra “the facts are the facts” (p3).

Human nature

Understanding heuristics and bias starts with understanding human information processing and the role of expertise in decision making. Humans rely on heuristics (mental short cuts), and these are often automatic and used without awareness.

Expertise-based efficiencies in processing and judgements also impact investigative decisions. It’s said that we don’t process information passively but interact with it and use our understanding of the world to interpret information.

These shortcuts are essential to navigate a large and complex world (with varying sources and degrees of danger). Shortcuts help us to focus on areas we believe to be important and other areas to ignore or reinterpret. As skill increases so too does the reliance on efficient shortcuts, and thus these cognitive processes become less consciously accessible to the decision maker.

This area includes a range of optical illusions and other heuristics and biases.

Personal factors

Factors here are largely hardwired things between individuals like their states, dispositions and beliefs. Little to no evidence exists for personal factors on workplace investigations but data from intelligence analysis and criminal investigation exists. Investigators differ on their tolerance for ambiguity and their need for closure.

A high need for closure pushes individuals to reach conclusions about what occurred more quickly and processing info with less depth than people without that strong need for closure.

Environment, culture and experience

Educational background shapes a professionals’ sources of bias, such as how they develop an initial hypothesis. One study of engineers found their understanding of safety “tended towards causal explanations that were more linear and focused on systemic causes whereas site managers were more multifaceted in their understandings of the factors which contributed to the event” (p3).

Time pressure is also related, where people trying to close a report quicker rely more heavily on intuitive cognitive processing over analytical. Fatigue also impacts judgements and cognitive strategies.

Organisational factors

An investigators’ organisational environment may also have cultural and structural pressures that bias judgement. Long hours, tight deadlines, heavy workloads, repeated exposure to emotionally distressing info may affect judgements.

E.g. an event which stimulates anger can promote more cognitive shortcuts whereas sadness encourages more careful understanding of the evidence and situation present.

Other sources of bias may include an investigator’s personal allegiance to their company. Further, another study found that workplace safety specialists higher in job status provide more worker-centred explanations for events, whereas those lower in job status provide more management or design factors.

Base-rate factors

Experience and skill generally support good judgements. However, experience can also drive decisions towards “conclusions not solely on the information at hand but also their experiences of event likelihood” (p4).

One study found that investigator base-rate knowledge “about a worker’s or equipment’s unsafe history significantly biases professional workplace investigators attributions of event cause” (p4). That is, predictably, an investigator’s own experience of how the world works influences how they believe an event played out, and can direct them towards base-rate fallacies.

Irrelevant contextual information

This area focuses on how information not relevant to the task at hand can influence judgements.

For instance:

Info is interpreted as more truthful and the person delivering the info as more credible when it’s accompanied by a non-probative image than the same info without an image.

The order of the info, where info is weighed more heavily the earlier it was encountered compared to info encountered later

Irrelevant info, such as info that has been shown to bias DNA and fingerprint expert analyses. In workplace investigations this could include opinions shared by witnesses and other opinions like “the driver was careless” or future projections like “this will happen again”. The author says that these statements can never be facts as they can’t be fact checked and verified as accurate.

Event specific information

The info available can also be biasing. This includes images, documents, tools etc. It’s said that such resources can influence judgements and that “the actual evidence is not driving investigators’ judgements but rather the resources they are consulting are shaping their cognitions” (p5).

Further, “When reference materials bias judgements it is often because professionals are not moving in a linear fashion from documenting the evidence, to comparing the evidence to references, to determinations of cause. Rather, the process is more circular: professionals consult the reference materials before or during their evaluation of the evidence and the consulted materials shape how investigators interpret the evidence” (p5).

An example is a cause analysis chart with a checklist of substandard conditions and actions. This resource influences people to fit evidence into the categories [* what-you-look-for-is-what-you-find.]

One study which explored the above cause analysis chart found that “The experts using the cause analysis chart also sought significantly less information about how the event occurred than those in the control condition” (p5).

The data

Certain data can be biasing. E.g. it’s unlikely the print of a tyre is biasing but industrial equipment that looks ancient and in disrepair may be biasing even if it’s irrelevant to an event.

Investigators who know the involved people may be biased by prior knowledge. Research has shown workplace investigators to allocate a disproportionately greater amount for responsibility for an event to worker action than the evidence supported.

This is fuelled by “a constellation of cognitive tendencies underpinning this investigative bias. For instance, the general belief that others’ actions are intentional … as well as our overemphasis of people’s dispositional qualities as the cause of their behavior (e.g., inattentiveness or carelessness)”. This blends with an overemphasis to underestimate contextual/situational factors.

The severity of the event also biases data search, interpretation and judgements. More severe events may nudge investigators to see worker decisions as more careless.

A large body of evidence supports the effects of hindsight bias, where people after the fact believed events to have been more predictable and preventable before the event. This may also affect investigators to believe events were more preventable than they were [* Fun game: count the number of times an investigation report/inquiry says that something was preventable…you’re going to need a lot more fingers for counting.]

Data that is more salient or distinctive may be more persuasive, like gender, ethnic group, organisational position or role, or types of equipment, can bias appraisals if it’s consistent with the investigator’s expectations.

Threats in the investigative process

A few factors were listed here. Confirmation bias is one that creates a tunnel vision, where an initial hypothesis overly influences final judgement. All of the biases above can feed this tunnel vision, where an investigator forms an initial hypothesis of the event and then seek out evidence to support it; at the same time minimising or ignoring info that contradicts their hypothesis.

Studies have found that investigators may collect just a fraction of available facts and halt their investigation once they reveal event causes which they can confidently endorse.

Coherence-based reasoning is another process-based bias, where new, salient and sound information stimulates investigators to update their leading hypothesis of event cause, they may instead and unconsciously, reinterpret the previously evaluated information to be consistent with the new hypothesis (rather than updating the hypothesis to suit the evidence).

Quoting the paper, “confirmation bias shapes how information is collected and interpreted as the investigation proceeds and coherence-based reasoning molds previously collected information into a coherent narrative of how an event occurred” (p5).

Other effects include bias cascade and the bias snowball effect. Bias cascade is when a professional’s opinion, shaped at one point in the investigation, biases other subsequent judgements later on. The bias snowball effect is when a professional shares info with other individuals, which contributes knowledge to the investigation and biases the content of the info shared by these other contributors.

The snowball effect “leaves the investigator believing that (s)he/they have independent and corroborating sources of information regarding the truth of a hypothesis, when, in reality, the corroborating opinions can be traced to a single source” (p5).

Potential solutions/debiasing techniques

I’ve had to skip a lot of this section due to length.

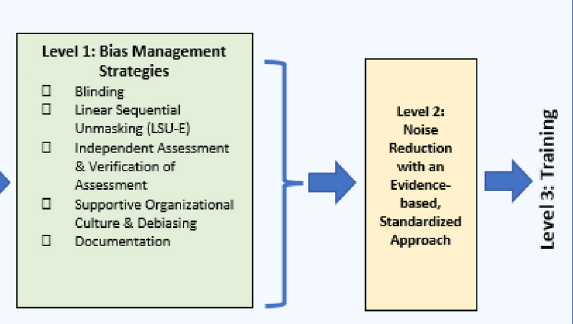

Includes bias management strategies. Some are:

- Blinding: Efforts to minimise irrelevant or contaminating info to investigators. This strategy is said to be effective, but requires a lot of care to consider what is necessary vs interesting. Some info is never relevant and should be eliminated.

- Linear Sequential Unmasking Extended (LSU-E). This technique controls the flow of info, so info low in contaminating/biasing potential is considered first, and then more biasing info considered towards the end of the investigation. An example is investigators examining all features of the environment, like tyre marks, prior to comparing the tyre patterns to a suspected vehicle. This is termed working linearly, as opposed to circularly.

- This isn’t always possible, however. An investigator’s prior knowledge or affiliation can bias prospective judgements. In these cases, it can be useful to have investigators document their alternative hypotheses.

- Independent assessment and verification of assessment. As noted, prior knowledge can bias judgements, thus “it is exceedingly difficult for an investigator internal to the organization to remain truly impartial and objective” (p7). Wherever possible having a person without personal connections to those involved, and as separate as possible is prudent.

- Information saliency to combat base-rate neglect. Use of up-to-date data can help frame judgements (or bias them, too). The author notes that “Only activated information can inform judgments (see “what you see is all there is”; Kahneman, 2011) and this base-rate information can then work as a datapoint in the investigation” (p7).

- Supportive organizational culture and debiasing. I’ve skipped most of this section, but use of alternative hypotheses is one technique. Another is to disrupt coherence-based reasoning – accomplished via considering why a conclusion could be wrong. Similar to devil’s advocate and red teaming.

- Noise reduction with an evidence-based, standardized approach. Use of more standardised practices with demonstrated inter and intra-investigator reliability may be useful. It’s noted that the majority of workplace investigation techniques and tools haven’t been empirically tested, with the exception of a few.

In concluding, it’s said that “knowledge about cognitive bias is not intuitive and must be explicitly taught” (p8). People believe they process the world accurately, and thus bias is often undetectable.

Investigators are also biased but some techniques may help to surface some of these sources of bias and noise.

Authors: MacLean, C. L. (2022). Applied Ergonomics, 105, 103860.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2022.103860

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/cognitive-bias-workplace-investigation-problems-ben-hutchinson

One thought on “Cognitive bias in workplace investigation: Problems, perspectives and proposed solutions”