One of the classics from Amy Edmondson (2004), exploring the relationships between group and organisational factors on drug administration errors.

Note: there’s lots to say and debate on the term “human error” (check out my site for several papers critical of the term), but for my own convenience I’m sticking with the terminology in the paper.

Providing background, it’s said:

- Cognitive and affective explanations (and likely more) exist explaining error

- People have expectations or frames, where we see what we expect to see

- Well-learned activities can be carried out with little conscious attention – allowing some pretty wild slips after the fact

- Affect and emotions (e.g. anger, anxiety etc) also induce error states

- From a systems lens, it’s noted the “nature of the system both influences the actions of individual operators and determines the consequences of errors” (p69)

- Systems can have, amongst many other characteristics, tight coupling and interactive complexity

- Tightly coupled systems “have little slack; actions in one part of the system directly and immediately affect other parts” (p69)

- Interactively complexity is characterised by “irreversible processes and multiple, nonlinear feedback loops. Interactively complex systems thus involve hidden interactions; the consequences of one’s actions cannot be seen” (p69)

- The system of administrating medications has qualities of interactive complexity (when you think about the whole dispensing and administration flow), and may not give immediate feedback that the wrong medication was administered

- As system design can “invite accidents”, so can straightforward solutions and interventions. Amy notes that “Organizational systems tend to resist straightforward solutions to problems” (p70)

- Organisational systems are “inevitably flawed” (p70), and thus an ever-present capability are “self-correcting performance units”

- Members of these self-correcting teams have a superb way of coordinating tasks anticipating and responding to each other’s actions and often appear “to perform as a seamless whole”

- An empirical example is from a flight crew on the effects of fatigue on performance. This study found that flight crews who had experience working together made less errors even when fatigued compared to well-rested teams that had no spent time together

- That is, the self-correcting teams were able to compensate for degraded performance due to fatigue, but only for team members experienced working with one another.

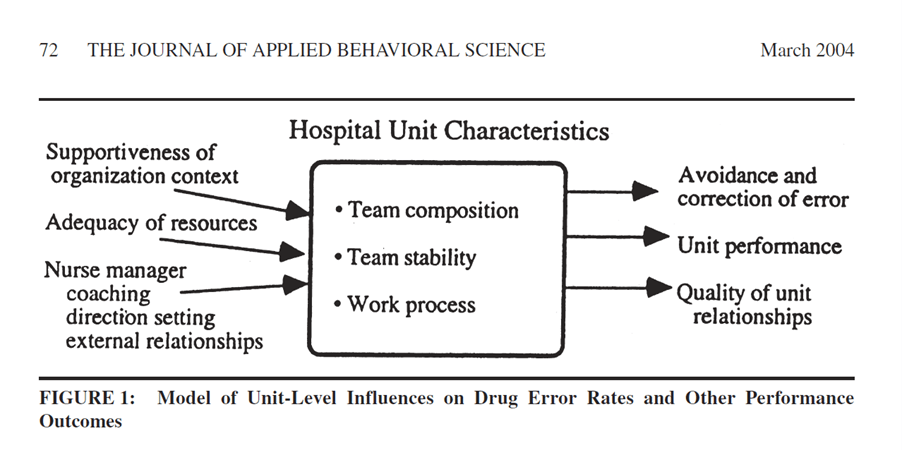

Below highlights the proposed relationships with error and team factors.

Results

While the author initially predicted higher error rates would be present in teams with lower perceived team performance, the opposite was found.

That is, teams with higher perceived team performance had a higher rate of errors.

Detected error rates were strongly associated with high scores on the nurse manager direction setting in the team, coaching, perceived unit performance outcomes, and quality of unit relationships.

Amy then proposes why would higher performing teams have more errors than lower performing teams. She reasons that, in fact, the higher performing teams have a higher willingness to disclose errors compared to the lower performing teams.

She notes that “in organizational settings in which errors are consequential, willingness to report may be a greater influence on the error rates obtained than is variance in actual errors made” (p79).

Higher detected error rates in the teams with higher mean scores on the nurse manager’s coaching, quality of relationships and perceived unit performance “may be due in part to members’ perceptions of how safe it is to discuss mistakes in their unit error” (p79) – in part, psychological safety.

Detected error rates were correlated with willingness to report errors and further, perceptions that people would not be blamed for errors was also, not surprisingly, correlated with detected error rates.

Teams with a higher rate of self-correcting behaviours (interceptions to identify and alert about errors in order to correct them), is said to provide an indication of the team’s performance. Teams with a higher number of interceptions tended to have higher scores on nurse manager direction setting, coaching, performance outcomes and quality of unit relations.

The data also suggested that teams with a higher number of interceptions were less likely to be concerned about being caught making a mistake, and more willing to report them.

The data indicates that the nurse manager’s leadership behaviours created an “ongoing, continually reinforced climate of openness or of fear about discussing drug errors” (p80).

In discussing the findings, it’s noted that nurse manager behaviours [but also any leader really, like a supervisor, project manager etc.) are an “important influence on unit members’ beliefs about the consequences and discussability of mistakes” (p86).

The way past and current errors are handled, discussed and the conclusions drawn then can strengthen ongoing conversations among unit members. In this way, “perceptions may become reality, as the perception that something is not discussable leads to avoidance of such discussions. These kinds of perceptions, when shared, contribute to a climate of fear or of openness, which can be self-reinforcing, and which further influences the ability and willingness to identify and discuss mistakes” (p86).

In wrapping up, Amy nicely adds that “These findings provide evidence that the detection of error is influenced by organizational characteristics, suggesting that the popular notion of learning from mistakes faces a management dilemma. Detection of error may vary in such a way as to make those teams that most need improvement least likely to surface errors—the data that fuel improvement efforts” (p86).

Author: Edmondson, A. C. (2004). The journal of applied behavioral science, 40(1), 66-90.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886304263849

Link to the LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/learning-from-mistakes-easier-said-than-done-group-human-hutchinson

3 thoughts on “Learning from Mistakes Is Easier Said Than Done: Group and Organizational Influences on the Detection and Correction of Human Error”