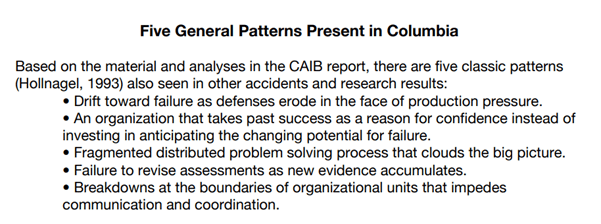

David Woods in his chapter from “Learning from the Columbia Accident” discusses five general patterns found across a range of major accidents as noted by Erik Hollnagel’s 1993 paper.

I’ll break this up into two posts – the full chapter and book are worth reading.

#1 is drift toward failure, where defences erode over time in the face of tightening production pressures. Goal tradeoffs “proceed gradually as pressure leads to a narrowing focus on some goals while obscuring the tradeoff with other goals”.

Moreover, “with shrinking time/resources available, safety margins were likewise shrinking in ways which the organization couldn’t see”.

It’s argued that extra safety investments are necessary when its least affordable.

#2 Past success taken as ensuring future success. Noted here is that some interpretations of danger are wrong, but rather just as concerning is the “the inability to re-evaluate the assessment and re-examine evidence about the vulnerability”.

Distancing by differencing is one mechanism at work here, where new evidence is discounted or doesn’t contribute to updating beliefs of risk because differences in the place, people, technology or circumstances are used to discount the relevance of the data.

That is, potential warning signs are discounted based on dissimilar surface conditions rather than recognising the deeper similarities.

This is said to run counter to operating practices/philosophies which proactively seek out disconfirming evidence to evalaute risk and expose an “organization’s blemishes” (e.g. chronic unease, preoccupation with failure, reluctance to simplify etc..).

#3 Fragmented distributed problem solving which obscures the big picture. For Columbia regarding the danger of foam strikes, “People were making decisions about what did or did not pose a risk on very shaky or absent technical data and analysis, and critically, they couldn’t see their decisions rested on shaky grounds”.

That is, there “was no place or person who had a complete and coherent view of the analysis of the foam strike event including the gaps and uncertainties in the data or analysis to that point”.

A veneer of objective technical data [** what John Downer has called “mechanical objectivity”] allowed people to support existing conclusions; thereby concealing other interpretations and not testing tentative hypotheses.

Author: Woods, D. (2004). In Learning from the Columbia Accident.

Link to the LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/benhutchinson2_david-woods-in-his-chapter-from-learning-activity-7044431929340809216-cHCS?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop

One thought on “Five common patterns of disaster – post 1”