Using 3 studies, this paper, with Adam Grant as co-author, explored the role of feedback seeking and feedback sharing from leaders and workers on promoting Psychological Safety (PS).

Providing background:

· Prior work highlights that when people believe they can take (interpersonal) risks without being punished, they speak up more often, generate more creative and innovative ideas, engage more in quality improvement work, and face fewer injuries and accidents

· Employees speaking up “often elicits insecurity on the part of leaders, who worry that it will threaten their images as competent” (p1574), and people hold back on voicing their opinions due to fear and futility

· This paper explores feedback-sharing as an alternative strategy for promoting psychological safety. Feedback sharing involves disclosing suggestions for improvement that one has received in the past, compared to the more commonly studied feedback-seeking approach, which involves making a direct request for information about how to improve

· Prior research has shown leadership is one of the strongest predictors of PS, and core antecedents of team PS is respect and trust – thus, how leaders engage with feedback is important to understanding trust and respect

· Prior work has shown that when people are asked questions, they feel more respected, understood and cared about. Moreover, “Leader feedback-seeking is an act of humble inquiry (Schein 2013) that shows interest in and grants status to employees” (p1575)

· Feedback-sharing is a form of self-disclosure, as it “involves showing vulnerability by opening up about how one has been criticized in the past and what areas of weakness one is striving to improve” (p1576)

· Notably, “When leaders share feedback, they are showing that they trust their employees enough to invite them backstage …. By acknowledging their own weaknesses, leaders demonstrate authenticity … which allows employees to see them as more human and approachable” (p1576)

· Prior research has shown that in psychologically safe teams, senior leaders were more comfortable sharing past criticism from more junior employees and admitting to their own mistakes

· Further, as leaders initiate their own vulnerability – employees respond in kind, a “a cycle of reciprocal self-disclosure” (p1577). Leaders that haven’t shared specific information about themselves are likely to not be role modelling self-disclosure and thus, employees are less likely to reciprocate

Way too much to cover in this paper.

Results

· Study 1 found that naturally-occurring feedback-seeking and feedback-sharing by CEOs independently predicted board-member ratings of top management PS

· Study 2 found that randomly assigning leaders to share feedback had a positive effect on team PS one year later, whereas assigning leaders to seek feedback didn’t impact PS

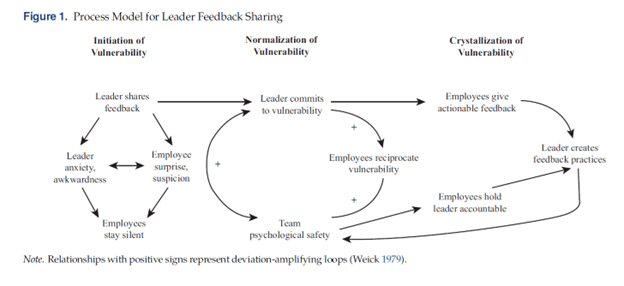

· Study 3, covered in more detail next, leaders were found to initiate vulnerability through seeking feedback, but this dissolved due to defensiveness and inaction. However, sharing feedback instead of seeking it “normalized and crystallized vulnerability as leaders made a public commitment to keep sharing and employees reciprocated” (p1574).

The interview study 3 revealed insights about the relationships with feedback sharing and seeking on PS. Notably, feedback-sharing didn’t necessarily have an immediate impact on team PS. Instead, feedback-sharing for leaders was an anxiety-provoking and awkward process.

For employees, feedback-sharing by leaders was surprising and resulted in discomfort. For other employees, they were sceptical or suspicious about the authenticity. Moreover, these engagements were often met with complete silence or as one leader remarked about sharing their feedback, “It was mostly crickets” (p1585).

Employees stayed silent due to a mix of emotions and uncertainty about how to respond to leaders in front of the whole team. However, in the resulting weeks and months, a cycle of improvement to PS began from leaders sharing their own feedback.

As the authors say, this process served as an act of disruptive self-disclosure that “signaled trust, normalized vulnerability in the team, and led leaders to continue sharing feedback” (p1584). This process was strengthen by employees reciprocating, who “responded to leaders’ displays of vulnerability by sharing their own struggles” (p1584).

This cycle, which promoted PS, crystallised the norm of vulnerability within the team; with some leaders actively blocking out time in their schedules and in one-on-one meetings to be vulnerable.

An important part of this process was that by leaders sharing their own feedback, this set actionable guidelines for areas of improvement that were a priority for leaders and fell within their own span of control. That is, leaders were role modelling how to give constructive feedback, and areas of improvement that were seen to be important. It’s said that “Rather than feeling constrained, employees appreciated having guidelines around what feedback to give” (p1589).

Overtime, these acts of vulnerability from leaders normalised vulnerability, making employees more comfortable speaking up.

The authors observed two core processes that helped to normalise vulnerability: 1) leader commitment, and

2) employee reciprocity.

As leaders shared their own feedback, they made public commitments to improving; a form of self-persuasion. And as employees experienced these leader vulnerabilities, weaknesses etc., they reciprocated in kind. Connections that followed from these processes “created space for leaders and employees to have deeper conversations without the feelings of risk normally associated with vulnerability” (p1588).

This process led to crystallisation of vulnerability over time – crystallisation referring to the extent that team members perceive the team culture similarly.

They then discuss why feedback-seeking may not have affected PS, where feedback-sharing did. When leaders sought feedback, this was initially seen by employees as a sign of openness and trust. But some leaders responded with defensiveness to the feedback; they also didn’t make the same level of public commitment to their weaknesses, and so employees did not reciprocate.

A model of the feedback sharing is shown below:

Authors: Coutifaris, C. G., & Grant, A. M. (2022). Taking your team behind the curtain: The effects of leader feedback-sharing and feedback-seeking on team psychological safety. Organization science, 33(4), 1574-1598.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1498

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/taking-your-team-behind-curtain-effects-leader-safety-ben-hutchinson

2 thoughts on “Taking your team behind the curtain: The effects of leader feedback-sharing and feedback-seeking on team psychological safety”