This study analysed 13-years of data from the Mine Safety & Health Administration’s (MSHA) database, incorporating 772 fatalities to see whether the safety triangle predicted subsequent injuries or fatalities.

The categories included:

- MSHS’s injury severity categories: near misses, MTIs, LTIs, permanently disabling injuries.

- Total lost and restricted days: 0 days, 1-16 days, 17-100 days, >100 days

- Average lost and restricted days per injury

- And some longitudinal regression models

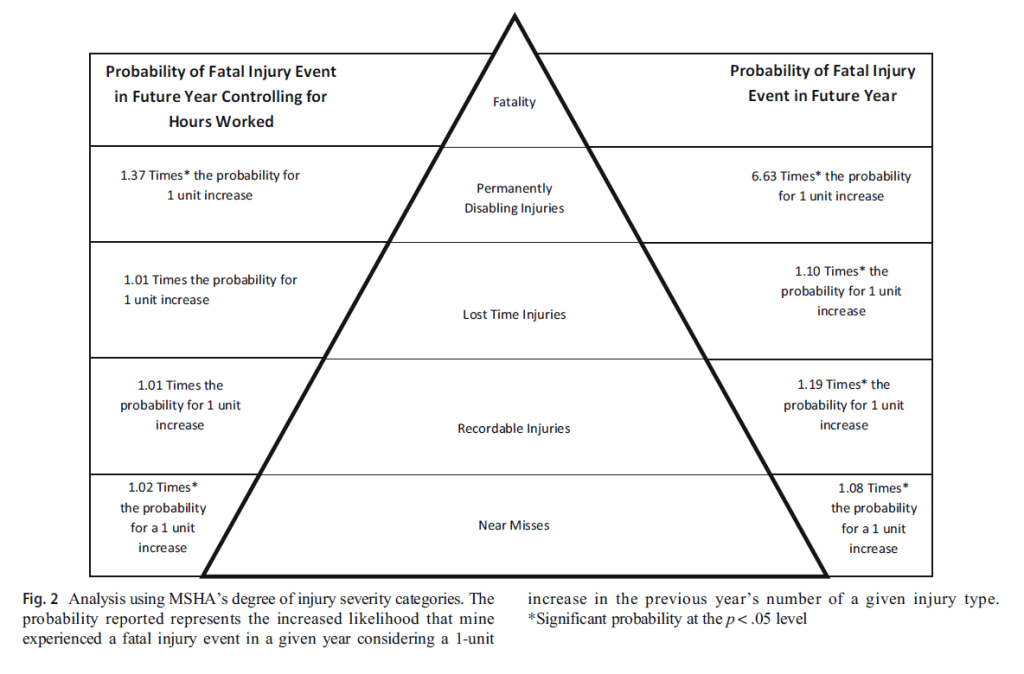

Because the hours worked by a mine may influence the chance that the same mine may experience a fatality, a comparison was made between hours controlled and uncontrolled.

Results

The authors say that their findings “demonstrate that near misses and lower severity events within a mine predict future higher severity events within that same mine, with some caveats” (p4).

Uncontrolled models indicated that an increase in near misses and each of the lower severity injuries within a mine increased the probability that the same mine will experience a fatality in a subsequent year, with authors noting “this predictive power indicates that fatalities may not exist in a vacuum but can be anticipated through patterns of lower severity incidents before the event” (p5).

For permanently disabling injuries, each addition resulted in a higher likelihood for a fatality within the same mine a year later. For uncontrolled hours, there was a 6.63 times (663%) greater likelihood for a fatality in a mine in a given year for each additional permanent disabling injury. With controlled hours, there was a 1.37 times (37%) greater probability.

For each additional days lost injury, there was a 10% increased probability for uncontrolled and for each additional reportable injury a 19% increase when uncontrolled. In both cases when controlled for hours, both dropped to 1% and were not significant. Each additional non-injury event, e.g. a near miss, resulted in an 8% increased probability for a mine to experience a fatal event in a subsequent year in the unadjusted model. When controlled for hours, there was a significant 2% increase in the probability of a fatal event.

For total lost and restricted days, compared to mines that had zero total lost and restricted, mines that experienced >100 in a given year were 17.34 times more likely to experience a fatal event when uncontrolled, and 2.69 times when controlled. For average lost and restricted days per injury, mines with >10 average days were 3.2 times more likely to have a fatality uncontrolled and 1.64 controlled.

Overall, as injury severity increases, a “systematic increase in the effect on predicting future fatal events is experienced, with caveats based on the severity delineation approach used” (p5). For uncontrolled, it would require approx. 83 near misses to equal the same effect on probability of fatality as one permanent disabling injury.

It’s said that total days lost and restricted provided the strongest predictive ability for a subsequent fatality (17.34 times), followed by permanently disabling injuries.

The authors state that “the triangular formulation does exist, but it is dependent upon the manner in which severity levels are defined” (p6). However, people must exercise caution when applying these predictive models because the strength of prediction is “directly dependent upon the severity delineation approach used” (p6).

Using three severity delineations in this work, the injury delineation with the strongest fatality prediction relationship in the subsequent year–irrespective of whether work hours are controlled for–was the total lost or restricted days delineation, including: 1) 0 lost or restricted days, 2) 1 to 16 total lost or restricted days, 3) 17 to 100 total lost or restricted days, 4) more than 100 total lost or restricted days.

For explaining some non-significant findings, the authors suggest that certain injury classifications, like days lost and reportable injuries may have less in common with the factors associated with fatal events compared to disabling injuries category.

Importantly, the authors state that these findings don’t suggest that reducing the number of near misses and lower severity safety incidents “produces a known/fixed decline in high severity events, they suggest that a decline of an unknown proportion can be expected” (p7).

Further, they say that even without establishing that events with different severity levels have a common cause, near miss and lower severity events were demonstrated to be significant predictors of future fatalities; and thus, according to authors, reducing those near misses and lower severity events should be expected to reduce the chance of future fatalities regardless of whether a common cause is shared.

They suggest that perhaps this comes about due to other factors, like cultural changes, leadership, risk management etc.

All the usual caveats exist around use of injury data, incident reporting/underreporting etc.

Authors: Moore, S. M., Yorio, P. L., Haas, E. J., Bell, J. L., & Greenawald, L. A. (2020).. Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration, 37(6), 1857-1863.

Study link: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42461-020-00263-0

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/heinrich-revisited-new-data-driven-examination-safety-ben-hutchinson