This brief paper examined “how the design of railroad systems and the organisational processes that create positive outcomes also produce the adverse safety outcomes associated with SPADs” (p1). They draw on sociotechnical lenses.

A SPAD is a signal passed at danger (when rail traffic passes a stop signal when not authorised to do so).

I believe it’s a conference paper from a much larger DOT report the authors published. As such, there’s larger, newer and more extensive investigations of SPADs, but I really liked the accessibility of this paper.

Providing background:

- Prior work for mitigating SPADs “revolved around investigating and disciplining locomotive engineers” (p2)

- However, these investigations “did not deeply explore the factors that contributed to the train crew proceeding past a stop signal. If the signal system worked as designed (e.g. it displayed a stop signal), the investigation stopped at demonstrating that the locomotive engineer passed the signal. The locomotive engineer had to defend [his or her] actions to avoid decertification” (p2)

- An earlier list of SPAD categories from RSSB listed factors like personal, attention/distraction, visibility, perception, read aspect, interpretation and action performance – primarily individual-level factors rather than upstream

- A sociotechnical system “integrates social systems and technology in a way that creates successful or unsuccessful performance … Outcomes reflect the complex interplay between social systems and technology” (p2)

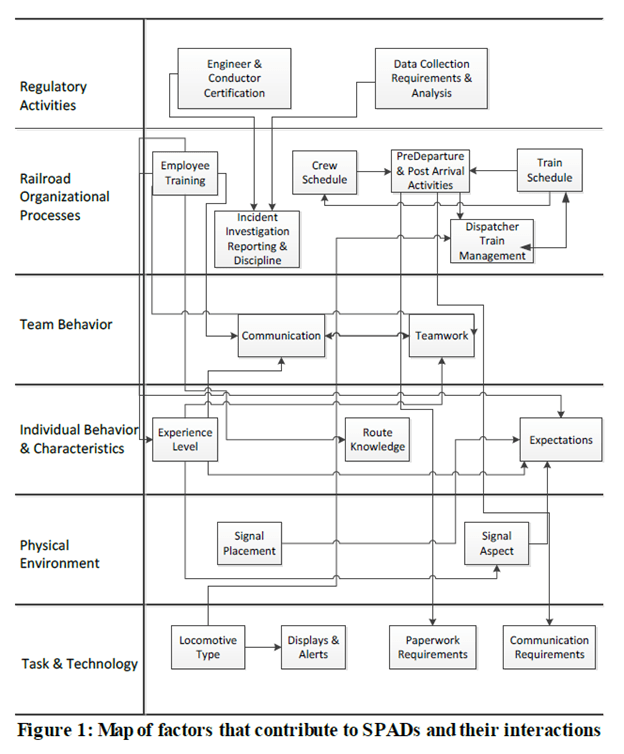

- They draw on Rasmussen’s approach, mapping how factors from across the sociotechnical system interact with each other to produce SPADs – image below.

The rest of the paper then discusses three changes (out of many) that took place over time in a rail organisation that impacted organisational performance in different ways to create “new opportunities for SPADs to occur”.

These changes included:

- Changes to the layout and structure of the terminal environment;

- Changes to policies and practices;

- And generational turnover.

1. Physical design and layout

The terminal environment was located in an urban area and evolved over time. Increases in population and infrastructure surrounding the terminal increased the demand for services while “simultaneously constraining the space available to meet that demand” (p5).

The physical rail infrastructure changed to accommodate additional train traffic into and out of the terminal, but was constrained by physical space. Over time these constraints coupled with increased train demands created a “complex web of tracks” and switches and signals.

Because of space limitations, signals were sometimes placed around curves, imbedded in walls, or placed low to the ground and obstructed by dirt. Placement of signals was dictated by track layout. Moreover, close proximity of tracks made it difficult to determine which signal belonged to which track.

On the passenger platform, signals were sometimes located behind the train because of growth of train length to accommodate larger populations. Hence, train engineers couldn’t always see the signal controlling the train’s movement from the cab.

Because of mismatches between train lengths and platform size, there was a lack of cues for engineers to know where to stop the train (depending on car lengths). Thus, opportunities were created for the train to stop in a poor position where the engineer couldn’t see the signal.

They also found that SPADs occurred more frequently in certain types of locomotives. Electric power locos were more prone to SPADs than diesel-electric (likely because signallers were more likely to give clear routes to diesel-electric locos, to avoid losing power in terminals).

Changes in loco design also impacted SPADs. Differences in where the engineer sat, controls and displays, location of the front window and more influenced how the engineer could see signals. They note that some seats were designed to encourage the engineer to sit forward, whereas other seats had the engineer more reclined – the latter making it more difficult to see dwarf signals.

Electric locos also provided simpler interfaces that “ locomotive engineers described as visually compelling and more responsive than the diesel-electric locomotives controls and displays” (p6). However, these visually compelling interfaces may have “led the engineer to attend more to the locomotive displays than to the signals displayed outside the cab and/ or take longer to respond to unexpected conditions” (p6, emphasis added).

2. Policies and Practices

Changes/aggravations in the “cognitive complexity” of signals also contributed to SPADs, with more combinations of signals for engineers to identify, interpret and respond to.

Importantly, permissive signals provided look-ahead information via different indications (e.g. a signal at location A provides a look-ahead on what signal B up ahead is showing). A “double-bind” is potentially created, where engineers are instructed to treat all signals (other than stop) identically, e.g. max speed of 10 mph, but then providing reliable look-ahead info but effectively instructing the drivers to ignore it and still maintain 10 mph.

This plays out in the environment of engineers trying to maintain schedule, creating a conflict between schedule and safety. Moreover, this “ambiguity created confusion among the locomotive engineers and variable responses to the signal aspects” (p6).

Changes in practices associated with the increase in the number of permissive signals was an increase in schedule pressure. During peak hours, nearly all platforms were occupied and trains constantly moving in and out of the terminal “with little slack”.

Production pressure came about as managers pressured dispatchers to keep trains on time, who instead of holding trains for all signals to clear, would send trains out or to wait in the terminal. This dispatching practice was suboptimal and increased the engineer’s exposure to stop signals.

3. Generational Turnover

Generational turnover also impacted the occurrence of SPADs. A large cohort of employees joined the railroads 30 years prior and retired around the same time. However, the rail operator hadn’t created an effective transition plan, nor how to upskill the new generation of workers (many without prior rail experience).

In the past, loco engineers, conductors and dispatchers would start out in other positions and work their way up. In the new world, people would be more likely placed in positions without that prior rail exposure. And thus, lack the domain expertise.

This large turnover created new opportunities for failure, like SPADs, “since much of the tacit information about how to operate safely remained in the heads of the retiring employees and was not documented anywhere” (p8).

Other typical issues were found where the training department was hampered by resource constraints and outdated materials. Moreover, new workers received less hours of training.

All of these factors combined, such as with inexperienced dispatchers, to “[create] traps for the locomotive engineers by routing trains in a way that increased the number of stop signals or taking away a permissive signal without giving the locomotive engineer enough time to react” (p9).

In discussing the findings, they note that “a complex interaction in the normal behavior by employees at different levels of the organisation that can contribute in multiple ways to SPADs” and this is driven by things like the “[design] of the infrastructure, decisions, equipment design, organisational policies, communication and coordination among teams and between departments and the day-to-day adjustments and accommodations made at all levels of the organisation” (pp9-10).

Authors: Multer, J., Safar, H., & Roth, E. (2015). In 5th International rail human factors meeting (London, UK).

Study link: https://rhf2015.exordo.com/files/papers/24/final_draft/024.pdf

My site with more reviews: https://safety177496371.wordpress.com

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/understanding-how-signals-passed-danger-occur-through-ben-hutchinson