This study explored factors supporting anaesthetists and nurses in managing complex everyday situations.

Cognitive task analysis was used with healthcare personnel following interviews.

Providing background:

· Over decades “the field of safety research has shifted focus from analysing adverse events and errors to understanding how teams and organizations can perform critical tasks and keep processes operational in the face of variations, disruptions and unplanned events”

· Resilience engineering is one approach to enhancing adaptive capacities to improve quality and safety, and how they arise from multiple interacting factors

· “Safety has been described as a dynamic non-event [3] and as something that is constantly present in professionals’ work processes”

· Resilience itself isn’t directly observable, but we can see the capacities for resilience reflected in its emergence in everyday work

· They provide a background on systems theory and complex sociotechnical systems. For one, the “characteristics of a complex task, in contrast to a simple task, derive from a system where its components have multiple and dynamic interdependencies [10, 11], making it difficult to predict how the system components will interact in response to a given situation”

· The above implies “that each system actor’s view is quite limited – and the faster decisions must be made, the more unpredictable consequences of actions are”

· Moreover, many official processes and protocols “reflect the work methods intended to meet the demands at the frontline (WAI – work as imagined), but because of the complex nature of many workplaces, with continuous variations and interdependencies, the actual work performed (work-as-done), is “never completely aligned with WAI”

· Resultingly, “resilient performance is dependent on the adaptive capacity of frontline staff managing both the gap between WAI and reality and the challenges that emerge when everyday work is done in a complex adaptive system”

· And I’ve skipped lots of other interesting stuff

Results

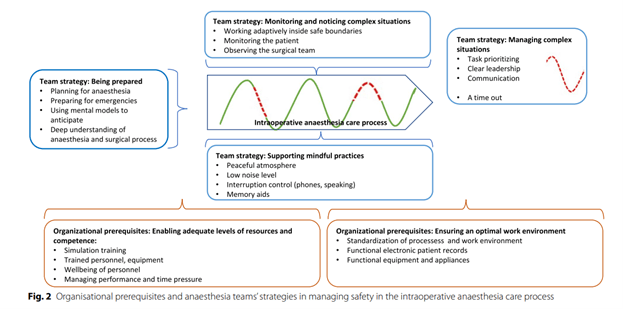

Participants described the preparation phase (relating to resilient potentials) involved anticipating variations etc. in the days prior to the surgery when procedures and team compositions were being selected.

Non-technical skills, involving use of mental models, were mentioned as a strategy here. In a previous study, nurses described the importance of planning for both expected and unexpected, using mental models to plan.

Interruptions are often present during immediate preparations and this may impact safe medications and the like. Use of checklists can help to provide necessary time set aside for sharing mental models and anticipating, although other research has shown variability in how checklists are used.

Participants mentioned mindful practice as an important strategy, like at the beginning of anaesthesia healthcare staff could include patients in sustaining safety by informing them about the procedure and care processes.

Communication was largely directed at the patient but also concomitantly allowed staff to share the process.

The preparations and anaesthesia induction processes were said to be the most task-intensive phases, with multitasking and interruptions. Active management of interruptions is necessary., and silencing sources of noises (phones etc.)

Similar phases are present in industries like aviation, with the “sterile cockpit rule” prohibiting unnecessary activities, like interruptions during critical phases.

However interruptions may sometimes be a type of adaptive capacity since they’re an inherent part of the care process and may trigger the team to communicate. Hence “interruptions should not be categorically prohibited – but the intention and timing should be considered beforehand, possibly by agreeing within the team on when and how interrupting is ok”.

Next they talk about situational awareness and how it is distributed across the system.

Communication came up again, with parties describing the importance of open, timely and honest comms. Here they note “Explicit reasoning in the form of thinking out loud and talking to the room has been shown to support the adaptation of coordination activities to meet the challenges in an emergent situation and is crucial to effective performance”.

Next they discuss leadership. I’ve skipped most of this since I think most appreciate the importance of leadership. They cite research indicating that leadership was positively correlated with team performance during non-routine and non-standardised situations. However, “in routine and highly standardized situations, leadership was negatively correlated with team performance”.

Therefore, “the ability to ascertain situations when care processes occur within safe boundaries, and where an anaesthesia nurse’s independent work can support and sustain high-quality teamwork is important”.

Also seen as important was for all professionals (nurses, anaesthetists and surgeons) to understand the surgical and anaesthetic processes. This allowed the team a shared baseline and shared mental models for working adaptively. Shared mental models allow better anticipation, prioritisation and understanding of future steps, and facilitates collaboration.

They note it could be argued that “one should be acquainted with the other professions’ work processes, in addition to one’s own, in order to anticipate and predict the complexity built into everyday team work”.

Also timeouts after each complex situation were performed in order to walk through and learn about the situation. This could be seen as “a form of in situ learning from both critical incidents and successful management of complex and demanding situations, developing mental models ahead of future challenges and thus adding to the adaptations”.

Next they looked at the organisational prerequisites for successful adaptations. Some of these factors were created well before surgery by “enabling adequate levels of resources and competence and stable teams”.

While sustaining a unit’s capacity for resilience requires “mindful adaptations from the managers” every day, managers are of course balancing demands against capacity in a complex environment. Hence, unexpected variance will require adjustments from workers.

Finally, they discussed the importance of standardisation of work processes for ensuring optimal work and managing complex situations.

SOPs provide a core for shared baselines. A balance is required around the use and updating of SOPs and also staff with deep knowledge and capabilities to adapt.

For guiding safe and efficient adaptations, they argue that “Processes and protocols should be described and documented, because working adaptively was found to be easier when done inside safe boundaries and when clear instructions were given”.

Resilient practices were said to require contextualisation, and concrete strategies for maintaining safety can differ between one clinic to another.

Link in comments.

Authors: Olin, K., Klinga, C., Ekstedt, M., & Pukk-Härenstam, K. (2023). BMC Health Services Research, 23(1), 1-15.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09674-3

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/exploring-everyday-work-dynamic-nonevent-adaptations-care-hutchinson-xvmcc

One thought on “Exploring everyday work as a dynamic non‑event and adaptations to manage safety in intraoperative anaesthesia care: an interview study”