This study explored procedure use via their Interactive Behavior Triad model (IBT), based on logics of the Model 1 / Model 2 concept.

Individuals were recruited from primarily oil & gas and chemical companies (n = 174 people surveyed).

Note. Model 1 / 2 isn’t Safety-I / II.

Providing background:

· They note that while procedures are designed to support safe work, incidents are commonly attributed to procedural issues

· One possible reason why is that organisations “continue to approach procedural systems with a focus on formal and rigorous social control that does not support decision-making when aspects of the task and context vary from what is written in the procedure”

· Model 1 conceptualises procedures as a means of standardising and controlling behaviour, and thus reducing unwanted variability and accident risk. This approach is argued by some to focus more on “fixing the human” [** which is a bit of an unfair characterisation, but whatever]

· Model 2 conceptualises procedures as ‘resources for action’, forming a type of cognitive resource, among other resources, for operators to draw on to make skilled judgements about adapting procedures to circumstances

· Model 2 is seen to align more with findings from some recent major accidents like Macondo and Montara, where factors outside of the individual’s characteristics influenced procedure use (e.g. climate and other system variables)

· Model 2 is said to focus more on the dynamic relationships among individuals and the systems which they work

· Prior research demonstrated that “system-level variables uniquely explained variance in procedure-related variables and outcomes” and that “system-level variables not typically associated with Model 1 (e.g., procedure quality) explained more variance than those (e.g., compliance attitudes) typically associated with Model 1”

· Leveraging a model 1 / 2 philosophy may help to better understand the dynamic relationships about how work is done versus how it’s imagined/prescribed by management

· Moreover based on prior research, workers’ use of procedures (by looking at the procedures as they perform their tasks) was typically dependent on: worker experience (more experience = less use), perceived procedure accuracy (more accuracy = more use), and task frequency (higher frequency = less use)

· Prior research, however, hasn’t deeply explored how many of these factors interact with each other to predict subsequent behaviour/procedure use in practice

· Hence, this study explored whether workers’ reported behaviours were linked with attributes of the workers, the task and the context where work is performed, and how these attributes interact with each other to predict behaviour

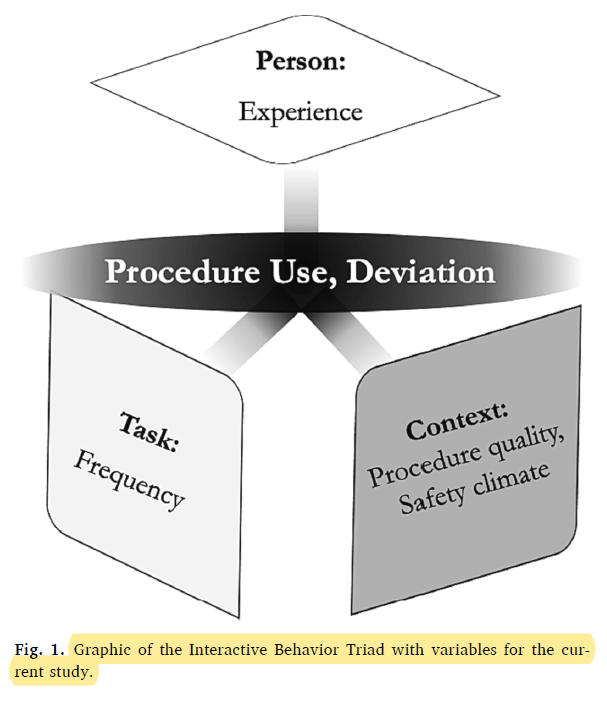

· They created the Interactive Behavior Triad (IBT) framework, which draws on a prior work of embodied cognition, task and artifact triad (I’ve skipped the description).

· IBT includes person-level characteristics, task characteristics, and contextual characteristics; see below

Results

Key findings included:

· No 2-way interactions between task frequency and either job position or industry experience was found on predicting procedure use

· However, a significant 3-way interactions between task frequency, industry experience and safety climate was found on predicting procedure use

· With poorer safety climate performance, both levels of industry experience (less and more) have similar impaired effects on procedure use

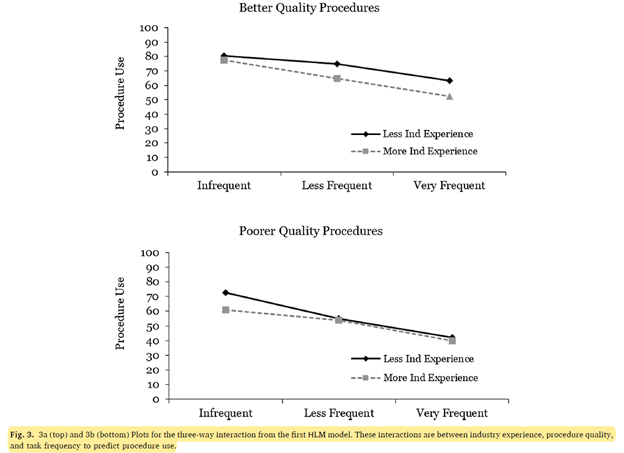

· A significant 3-way interaction between industry experience, procedure quality and task frequency was found

· For better quality procedures, the difference between more and less experienced workers’ procedure use is greater when the task is performed either very or less frequently, compared to tasks performed infrequently

· For poorer quality procedures, individual experience impacts procedure use mostly with infrequent tasks

· Workers who are less experienced in their position tended to have similar reported use of procedures in both low and high quality procedure conditions, whereas more experienced people were more influenced by procedure quality

· Procedure use was found to decrease as task frequency increased

Looking at the 3-way interactions, it’s seen that the contextual factors of safety climate and procedure quality interact with industry experience to reduce the negative effects of task frequency.

They note that “positive safety climates and procedure quality both reduce the task frequency effect on procedure use for those with less industry experience—specifically, their use of procedures does not decrease as much as those with more experience”.

For poorer quality procedures and poorer safety climate, people with more experience have lower procedure use for infrequent tasks.

Moreover, better quality procedures have more impact on those with more position experience, e.g. better quality procedures result in less procedural departures in people who are more experienced, whereas less experienced people are less affected by procedure quality.

They say that it is “concerning that those with more industry experience have lower procedure use for infrequent tasks given that these were done 1 – 5 times per year” and that given the infrequency, forgetting a step or not being cognisant of a procedural change would be a risk.

Nevertheless, the finding that procedure use decreases as frequency increases isn’t surprising, and this has been shown in prior work, as steps become automatic. This automaticity due to frequency is more efficient, but in the context of safety-critical work may sometimes be problematic.

Whereas companies may try to encourage workers to always follow a procedure even for frequent tasks, the “results here suggest that this does not always occur”. The findings suggest that instead of beating the drum harder, perhaps more efforts should be placed on improving the quality of the procedures and elements of safety climate to off-set the worker experience and task frequency effects.

Discussing the merits of model 1 and 2, which they state is not to pit one concept against the other – they argue that these findings suggest that “unitarian … [views] of precursors to procedure-related behaviour … cannot represent the complexity of the interdependency among the person, task and context”. That is, simply viewing procedures as something that must be followed irrespective of context and, perhaps by extension, viewing people simply as rule-following robots, doesn’t represent reality and these findings challenge the notion of procedures as always appropriate.

Model 2 thinking is seen as a ‘trinitarian’ view of procedural systems and characteristics. Hence, “Dekker (2003) argued that in Model 2, completing a task is a substantive cognitive activity and the work involved can never be completely prescribed by written procedures”.

Nevertheless, model 1 and 2 both have their places; where model 1 thinking may be more suitable for novice workers, infrequent tasks and possibly more hazardous tasks, providing considerations are given about the actual context. They argue that “Hendricks and Peres (2021) provide evidence that Model 1 is likely necessary but not sufficient for understanding procedural systems” (emphasis added).

For practical implications they state that:

· We must be interested in ensuring that procedures are high quality and worth the time and effort

· High-risk organisations should continuously monitor safety climate as this impacts procedure use (but has varying influence depending on worker experience and task frequency)

· Step-level sign of (signing off as each step is completed in a procedure) “is likely not a reliable method for ensuring procedure use”

· Based on the findings, procedure use wasn’t found to be high for all tasks requiring sign-off. Although workers do use procedures more frequently when sign-off is required for frequent tasks, this effect isn’t found for infrequent tasks

· Hence, “use of procedures when signoff is required is a function of task frequency indicates a tension between the goals of the worker (workers use procedures when they are perceived to be useful) versus the goals of the organization (having workers use the procedure every time for those procedures with signoff)”

· Again quoting the paper, previous research observed workers “signing off on all the steps after the task had been completed (aka,“pencil-whipping” … suggesting that including signoff on procedures is an unreliable method of ensuring that workers use procedures”

· Therefore, this “tension illustrates the fallacy of an exclusive Model 1 approach—one with formal and rigorous social control—and could possibly be resolved if procedures are designed or presented differently based on task frequency—a Model 2 approach that focuses more on developing work practices (e.g., procedure use) based on how work is done”.

Authors: Peres, S. C., & Hendricks, J. W. (2024). Safety Science, 172, 106328.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106328

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/systems-model-procedures-high-risk-work-environments-2-ben-hutchinson-z0psc

One thought on “A systems model of procedures in high-risk work environments: Empirical evidence for the Safety Model 2 approach using the Interactive Behavior Triad”