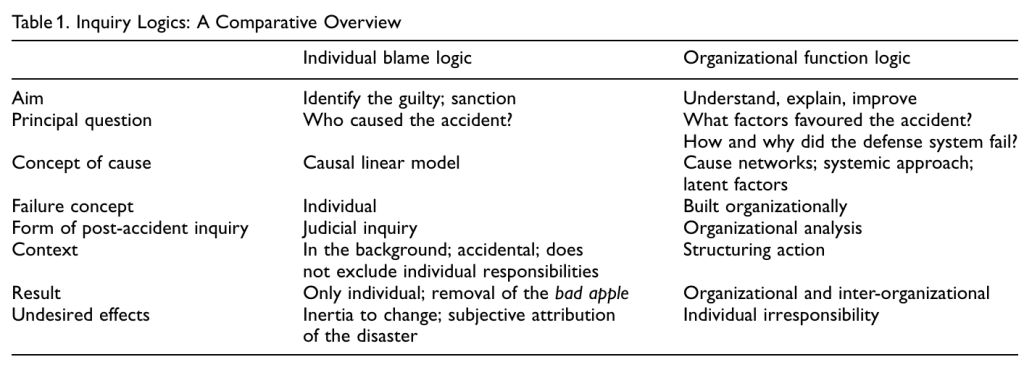

This study explored two different approaches to explain failure in an organisation:

· The first is an individual blame logic – this seeks to find a guilty individual

· The second is an organisational function logic – this aims to identify org. factors that favoured the event.

The paper discusses both logics and their consequences and draws on accidents involving unintentional actions for reference.

The individual blame logic (IBL) is said to often beat out the organisational function logic (OFL). IBL is an accusatory approach, aiming to identify guilty individuals. It’s typical of criminal law, but “is also prominent in organizations based on a punitive culture”.

The approach also fits snuggly with the societal need to identify clear causes for accidents.

OFL in contrast is an organisational approach intending to identify system factors which contributed to the event.

The paper presents a medical accident resulting in the death of a patient. I’ve skipped most of it, but in short a 65 year old man was hospitalised for an emergency. The first treating Dr goes on vacation, with a new doctor taking over care. The second doctor copies the prescription from the first doctor.

The patient’s condition rapidly worsens. Several causes are considered – like infection, but nobody considers the dosage of one of the prescribed medications.

The authors argue that the quest for the explanation can be, at first, straightforward: one of the prescribed drugs is normally prescribed at 5mg, not 50mg as was prescribed. If administered in the latter (for other conditions), it has to be co-administered with a vitamin (which reduces the harmful effects).

The patient was treated with a drug dosage 100 times what was necessary, and the dosage error wasn’t noticed by:

1. by Dr. First,

2. by Dr. Second,

3. by the doctors on duty in the afternoon,

4. by the anaesthetist,

5. by the intern,

6. by the pharmacy.

From the IBL perspective – who made mistakes, and who made has made the most prominent mistake? From the OFL perspective, what org. factors favoured this mistake?

They argue that based on the reported facts in the paper, we can’t actually answer the latter.

IBL perspective

The IBL view starts with the assumption that people make mistakes because they aren’t paying attention. It constructs a linear model of causality, leaving the organisational factors “mostly in the background”.

Efforts towards blame are directed towards the frontline. By attributing blame, “the ‘bad apple’ will be removed or prosecuted”.

The IBL, ostensibly, seems to be based on some valid logics:

1. People’s actions are voluntary. They’re free agents choosing between safe and unsafe behaviour. This is highlighted by research indicating 80-90% of accidents being the result of human actions. Hence, “because human actions are perceived as subject to voluntary control, then accidents must be caused by negligence, inattention, inaccuracy, incompetence, etc.”

2. Responsibility is individual; it lies with people

3. Sense of justice is strengthened. The IBL is emotionally satisfying

4. Convenience. Targeting individuals “undoubtedly has advantages for organizations from the legal and economic point of view”. It also lets organisations maintain their structures, rules, and power systems with alteration

The IBL approach targets individuals and their actions and errors. It’s easier to find frontline operators in complex human-machine systems, since they’re directly interfacing with the proximal factors of the event. Conversely, “hidden factors of the organizational and managerial aspects”, being products of collective actions, are “diffused in time”.

With OFL, there’s an increasing recognition that mishaps are “inextricably linked to the functioning of surrounding organizations and institutions”. OFL operates under the logics that performance variability is inherent to the human condition and we can change the conditions under which people work more readily than the human condition.

While OFL recognises the proximal connection between events and human action, it also acknowledges “these mistakes …are socially organized and systematically produced (Vaughan, 1996)”

OFL recognises active and proximal factors by people, but also upstream latent factors which incubated the event via “temporal pressures, equivocal technology with ambiguous man–machine interfaces, insufficient training, insufficient support structures” and more.

They cite Chernobyl and Bhopal as examples that “were not caused by the coincidence of technological failures and human errors, but by the systematic ‘migration’ of the organizational behaviour towards the accident”.

OFL challenges the logics of linear causality. They note that accidents can thus appear to be “objectively different under the two logics”. This is because people/groups select from “the abundance of facts what is relevant for inquiry” based on their goals and worldviews. Findings are therefore constructed, more than being found. Hence, “the search for a cause is inevitably tied to the point of view and interest of who is making the inquiry”.

By identifying people at fault, the IBL increases the chance that the “organizational system will continue to function with the same organizational conditions” that contributed to the failure.

Moreover, via an IBL logic, the organisation is unable to understand it’s own vulnerabilities, creating a type of organisational change inertia. The identification of scapegoats following disasters and blame of individuals allows individual responsibility to be split from the organisation.

The OFL logic changes the questions following accidents from “who caused the accident”, to what were the conditions and mechanisms that allowed the event to occur. This is important since decades of research suggests that major accidents “are not generated by a single cause but by a number of interrelated events which taken singularly can appear to be totally insignificant and not influential in the origin of the accident”.

Limits of learning from accidents

The paper then talks about organisational learning, relating to Argyris & Schon’s concept of single loop and double loop learning. They also delineate passive and active learning approaches.

Passive learning in this context is said to be the type by acquiring and sharing accident reports and the like. The active learning approach requires a wider awareness of the event and an understanding on the daily activities and risks of work.

Here, “Active learning from accidents proves to be very difficult in real life”; usually represented instead by superficial learning.

They talk about other challenges of learning. One is a type of organisational myopia, which “which inhibits the analysis of signs, as well as reports and complaints by people”; which is accompanied by instances of signs which are intentionally hidden.

Drawing on Sagan’s work, they discuss four barriers to learning:

(1) highly ambiguous feedback for organizations

(2) politicised environments which shape what is considered hazardous, what is found, and what is fixed; ultimately protecting the interests of those with power

(3) information related to an event is incomplete and inaccurate

(4) the non-disclosure, intended as compartmentalization inside the complex organizations, is the disincentive to share information

Concluding their arguments, they note that:

· Given the emphasis on avoiding individual blame, there is also a potential danger of overlooking valid individual responsibility

· In their view, “Arguably, there are positive aspects to blaming. It is difficult to deny the deterrence aspect of blame particularly with legal processes” [** I’m not sure how well this argument holds up in H&S prosecutions and deterrence, though]

· Substitution tests are also problematic, since, “people who are substituted will be subject to the effects of the same culture and structure. In fact, every remedy which is limited only to individuals leaves the structural origin of the problem unvaried”

· Reorganisation and change efforts that “ignore the networks of power and interest are destined to failure and therefore remain without consequence”

Authors: Catino, M. (2008). A review of literature: individual blame vs. organizational function logics in accident analysis. Journal of contingencies and crisis management, 16(1), 53-62.

My site with more reviews: https://safety177496371.wordpress.com

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/review-literature-individual-blame-vs-organizational-ben-hutchinson-eqy1c

2 thoughts on “A Review of Literature: Individual Blame vs. Organizational Function Logics in Accident Analysis”