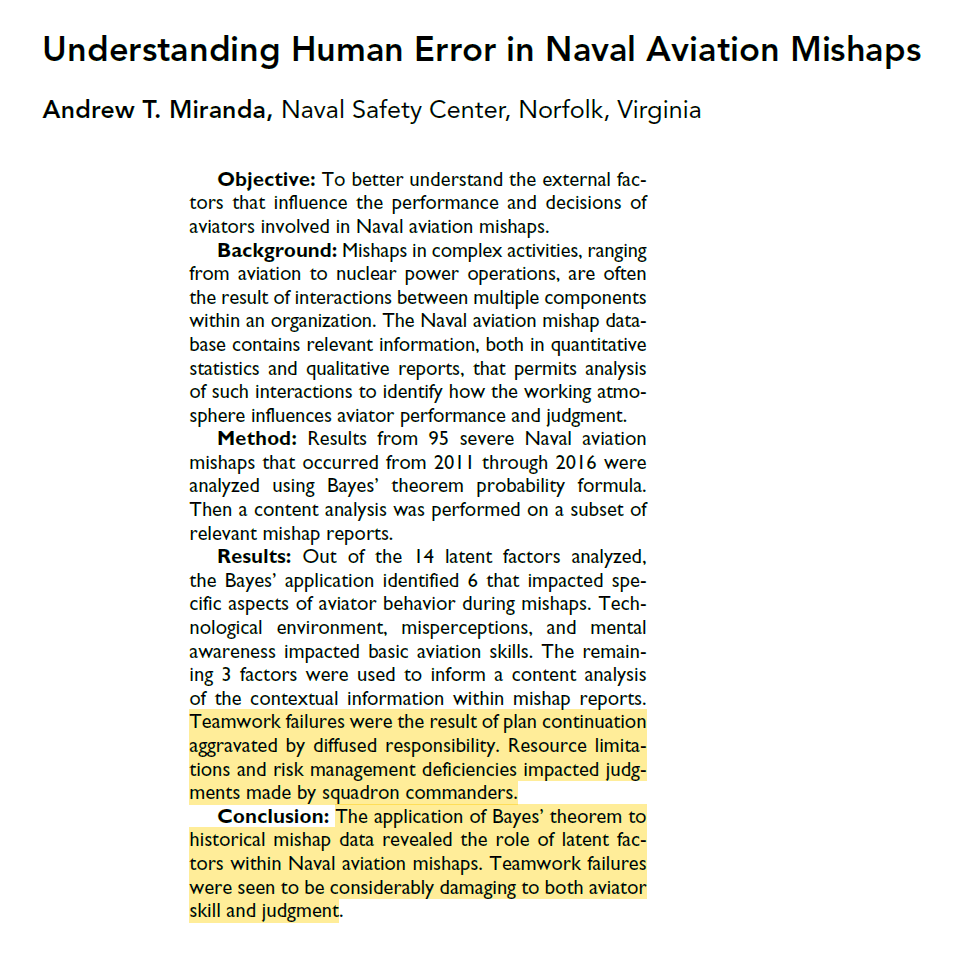

This was interesting – it studied 95 severe naval aviation mishaps.

The incidents were evaluated using the DoD HFACS model, the applicability of HFACS was then evaluated , and then a sample of events thematically evaluated a sample of events.

They drew on the delineation of errors into performance-based (PBE) and judgement/decision-making (JDME), as per the DoD HFACS model.

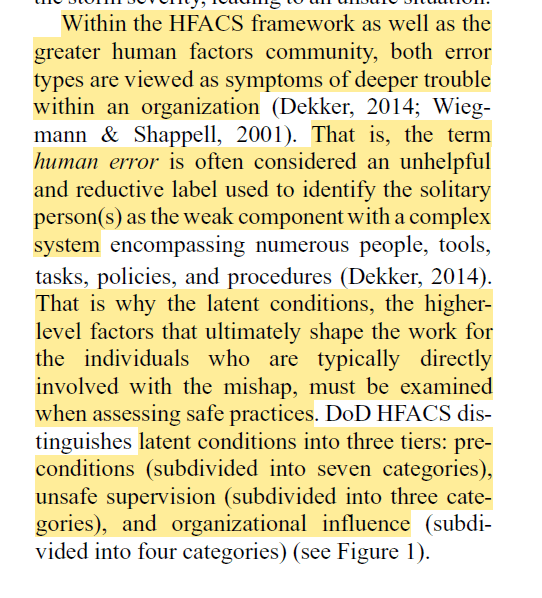

It’s argued “error types are viewed as symptoms of deeper trouble within an organization …That is, the term human error is often considered an unhelpful and reductive label used to identify the solitary person(s) as the weak component with a complex system”.

Findings were:

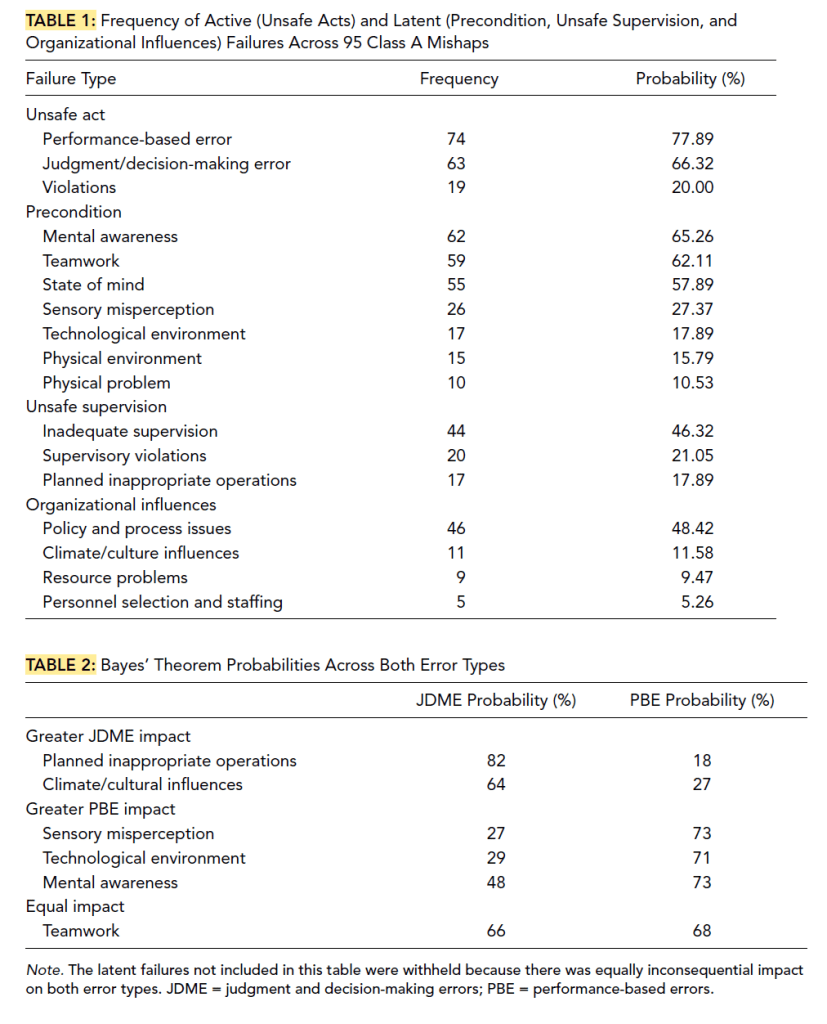

· The first findings – the accidents mapped against HFACS, were largely uninteresting (see attached image)

· The Bayes theorem analysis was a bit more interesting – they note that five total latent failures produced different levels of impact on the two types of errors

· Planned inappropriate operations and climate/cultural influences were heavily influenced JDME

· Sensory misperception, technological environment and mental awareness more heavily influenced PBE

· Teamwork “was the only latent failure that provided equal substantial impact on both types of errors”

· They note that the technological environment connects with the overall workplace design, e.g cockpit and display designs, controls etc

· Although just 17 mishaps cited the technological environment “the current findings demonstrate the profound impact it plays in disrupting basic aviator skill principles”

· Moreover, prior research highlights that factors of aviator awareness and perception “

· have emphasized the necessity of well-designed technology for effectively displaying information to the aviator for maintaining safe performance”

· Also, the latent failure “planned inappropriate operations” may suggest that “aviators are put into unfamiliar situations and therefore situations with increased risk”

· Reflecting on the incident classification systems/taxonomies, “they are not effective at being able to capture information relevant to the context and constraints workers faced when being involved in an accident,

· The systems are too reliant on hindsight bias, which “hinders a deeper understanding of why individuals did what they did and particularly why they considered that their actions (or inactions) would not have led to a mishap at the time”

· Finally, such error systems can “unintentionally direct accident investigations in such a way that provides an arbitrary stop-rule for the investigation

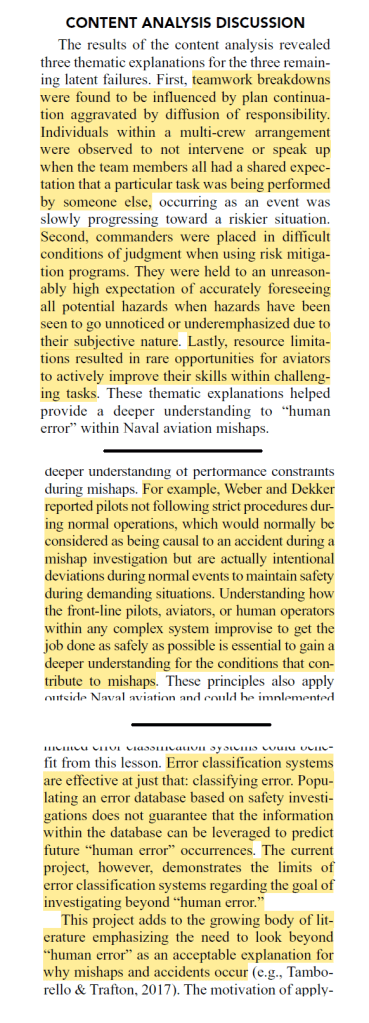

More interesting was their qualitative analysis of the events – seeking a way to overcome the inherent limitations of the taxonomic approach by exploring context and real-world constraints.

They found:

· Plan continuation was found in the data, being “ human operators do not notice that a situation is gradually deteriorating from safe to unsafe”

· People instead first notice clear and unambiguous cues and not necessarily ambiguous and “seemingly harmless” issues

· This issue is exacerbated by “the social dynamics of diffusion of responsibility”

· This is exemplified with the bystander effect, being the social tendency for an onlooker intervention during an emergency to be suppressed by the “mere presence of other onlookers”

· And, “As an unsafe situation is unfolding, an onlooker will observe other onlookers not intervening, thus confirming that this situation must not be an emergency”

· 18 of 22 mishaps revealed teamwork breakdowns, such that the beginning of a mult-crew event appeared at first to be benign and manageable, but progressed to an unstable and unsafe state but “not obvious enough to signal to the aircrew that they should stop”

· These factors “evoked conditions that allowed small, subtle changes and threats to go unnoticed, eventually making it more difficult to recover from error”

· 13 of 23 mishaps “revealed that squadron commanders were given unreasonable expectations to algorithmically identify the exhaustive collection of hazards and risks”

· Said differently, commanders are held to “unreasonably high expectation of accurately foreseeing all potential hazards when hazards have been seen to go unnoticed or underemphasized due to their subjective nature”

· These expectations “are incompatible with human judgment in general, including the ability to assess or anticipate risk”

· Moreover, there was an “expectation that the risk management document and program was expected to identify unusual risks unique to the current event”

· “Like plan continuation previously mentioned, only hindsight would reveal that cues would have been subtle and gone unnoticed by risk assessors”

· They also observed that there was limited opportunities for pilots to undertake deliberate practice of challenging tasks; aggravated by resource limitations

· They talk about how departures from rules are seen to be exceptional, when pilots may not routinely strictly following all rules during normal operations

· And “Understanding how the front-line pilots, aviators, or human operators within any complex system improvise to get the job done as safely as possible is essential”

Ref: Miranda, A. T. (2018). Understanding human error in naval aviation mishaps. Human factors, 60(6), 763-777.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1177/0018720818771904

My site with more reviews: https://safety177496371.wordpress.com

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/understanding-human-error-naval-aviation-mishaps-ben-hutchinson-algfc

3 thoughts on “Understanding Human Error in Naval Aviation Mishaps”