This discussion paper from de Vos, Dekker and others discusses applying Just Culture and Safety-II to improving from healthcare sentinel events.

I think it’s based on de Vos’s PhD.

They start showing some evidence that among hospitals convinced that they have a “blame-free” culture also “reported that culpability was of primary concern in their investigations of sentinel events”.

Crucial aspects of Just Culture (JC) is creating a safe, blame-free environment as a essential precondition.

Just Culture: victims first

JC balances safety and accountability, particularly after events.

JC approaches are said to emphasise learning from mistakes “without a focus on blame” and focusing on systems improvement “ instead of individual punishment”

Following a sentinel event a natural tendency is to “hold someone accountable for the situation (retribution), while there is also a great need to work on recovery for the future (restoration)”.

It’s argued that JC theory “stipulates that learning and punishment are not a good match”. If learning is a key objective then the focus shouldn’t be on retrospective culpability or retribution “but rather on forward-looking accountability”.

Shifting focus from retribution to restoration

Traditional approaches for JC are said to be focused on being clear about ‘the line’ between acceptable and unacceptable behaviour. These logics suggest that culpability remains acceptable for “reckless behavior”.

But recklessness and negligence are judicial terms and not necessarily suitable for this purpose.

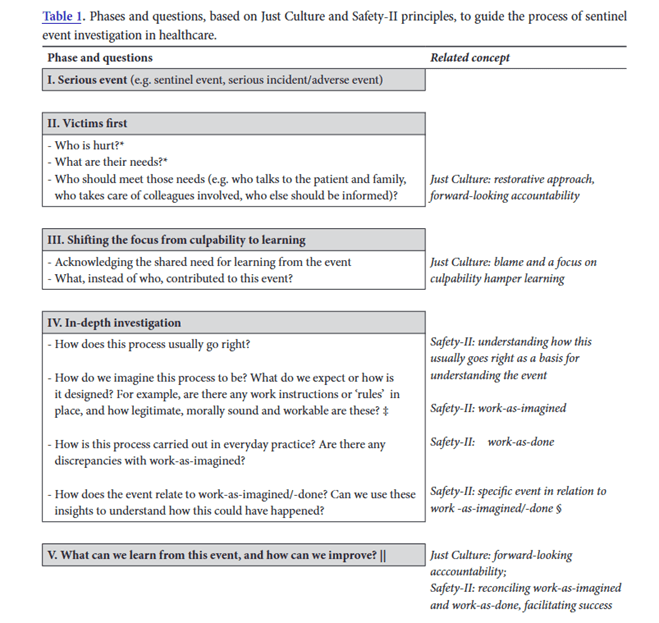

They provide several prompts for guiding a restorative approach below:

They argue that it’s “difficult, disputable and context-dependent” to be able to differentiate between unacceptable and acceptable behaviour, and the “The line between tolerable and culpable behavior is not fixed a priori”.

The ‘line’ must be drawn repeatedly by those “with the position, capacity and responsibility to do so”. It also tends to be based on several subjective judgements “about supposedly ‘normal’ clinical standards”.

Retributive approaches are characterised by questions like these:

· Which rule is broken?

· Who did that?

· How severe is the breach?

Judgements about these questions will be affected by knowledge of the severity of the outcome (outcome bias), and “the distortive effects of hindsight bias”.

The perspective of external parties, separate to the situation will be different from perspectives of clinicians facing these dilemmas.

Retribution is a process

They say retribution occurs removed from the rest of the community and victims. Creating an openness to different accounts of what happened is “easily sacrificed in an adversarial setting”, which favours one account over the other. Patients and other professionals may feel left out of the process “without much of a voice”.

It’s said that “Retributive approaches can also encourage ‘offenders’ to look out for themselves”

Restoration and looking after all victims

Restorative approaches are said to emphasise looking after victim needs. The focus is on what clinicians, patients and all consider serious and important, focus on their hurt and what’s needed to restore the damage, trust and relationships. Also, clarity around who has the obligations to meet those needs.

As per the above image, restorative approaches ask these sorts of questions:

· Who is hurt?

· What are their needs?

· Who should meet those needs?

They cite an example that patients and families resulting from a sentinel event felt left out of the process, and were told to wait for the official formal investigation “with too little attention to their needs, such as early disclosure and apology”.

A focus on recovery should be the first response and should precede in-depth investigations, ‘witness statements’ etc.

Per their words, “victims first, analysis second”.

Can somebody, or some act, be beyond restoration?

Next they explore whether some acts can truly be beyond restoration? I’ve skipped a bit of this, but briefly, retributive counter hurt with more hurt (blame and punishment), hoping this will “somehow equalize or even eliminate the injustice that has been inflicted”.

Restorative approaches believe that pain requires healing.

They say that regarding accountability and responsibility, it’s difficult to cleanly and objectively ascribe personal responsibility to people when “more system-level problems are in play,

such as when admitting a patient to a ward that is understaffed”

They say that the important question in these instances is: “who gets to decide whether a case is beyond the reach of restorative approaches, and what are their stakes (if any) in saying it is so?”.

[** Although it’s not discussed in this paper, this reflects the importance of power and politics]

Importantly – “Restorative theory should not be interpreted as a means to provide with immunity from prosecution of criminal behavior of professionals”.

Separate processes should remain in place to enable investigations of suspected criminal acts or misconduct. They say that these investigations are set up for answering questions from criminal law. In contrast, sentinel event investigations should be about learning and improvement.

Hence, “these judicial questions do not have a place in the learning reviews” following sentinel events.

Promote restorative practices internally

JC approaches are said to restore relationships that have been disturbed by the event. They find solutions to meet the needs of all involved parties.

Research shows that patients who experience harmful events or errors “want apologies, explanations and assurances that lessons are learned from their experience”, rather than necessarily punishments.

All of these assurances can be achieved with a restorative approach, but this involves “active effort to resist a natural tendency to search for a cause and to hold someone accountable”.

This involves asking who is hurt, giving a voice to everybody, and identifying the responsibilities and obligations, what needs to be done, and how the organisation and community can achieve these solutions and feel part of the solution.

Safety-II: everyday practice as the basis for investigations

An in-depth investigation came commence once “the hurts and needs of those involved have been identified in a way that is respectful to all the parties involved, an in-depth investigation can be initiated using the Safety-II approach”.

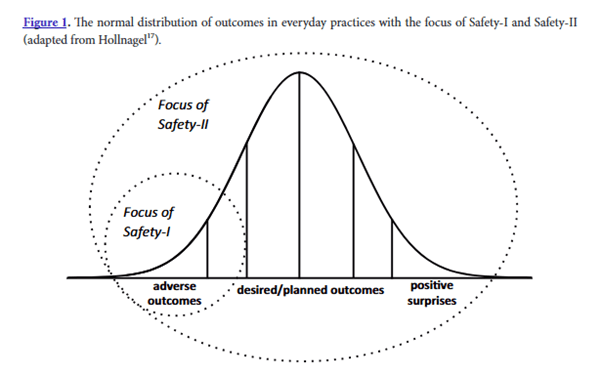

This approach is a “natural extension” to Safety-I approaches. S-II “expands the focus of learning because it aims to understand the ability to ensure safety, by examining how work processes in everyday practice usually go right, thus situations in which safety is present or ‘created’”.

S-II is based on the notion that greater learning comes from understanding how a process normally functions in everyday practice, and finding ways to support the ability to achieve success.

S-II views that the same processes underlie when things go right or wrong, due to the natural variability in complex adaptive systems.

Further, “When we identify a ‘human factor’ as root cause for a sentinel event, we fail to appreciate that this same factor more often has positive contributions, and has essential adaptive capacities in many other situations”.

Hence, to understand how ‘safety’ is created, we need to look beyond unsafe situations or absence of safety but also to how our people and systems create safe and reliable performance.

Performance variability is shown below:

S-II approaches can help to reveal the “messy reality’ of everyday practice”, representing a more realistic and representative starting point for learning.

This approach allows us to also look at how to ensure successful performance, which “also entails that such negative events do not emerge”

Quoting the paper, some questions that result from this approach include:

· How does this process usually go right?

· How do we imagine this process to be? (i.e. work-as-imagined)

· How is this process carried out in everyday practice? (i.e. work-as-done)

They talk about some ways to apply these ideas but I’ve skipped this.

Ref: de Vos, M. S., Dekker, S. W. A., den Dijker, L., & Hamming, J. F. (2017). A perspective on applying Just Culture and Safety-II principles to improve learning from sentinel events in healthcare. Healthcare improvement based on learning from adverse outcomes, 161, 179.

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/perspective-applying-just-culture-safety-ii-improve-from-hutchinson-hdopc