An interesting paper from Mark Cannon & Amy Edmondson about failing intelligently.

Opening the paper they argue that while the idea of organisations learning from their failures is obvious – “yet organizations that systematically learn from failure are rare”.

They’ve also found that few organisations effectively experiment to learn, which requires by necessity generating failures while discovering success.

They argue that learning from failure involves skilful management of: identifying failure, analysing failure and deliberate experimentation.

They also argue that many managers “underestimate the power of both technical and social barriers to organizational learning from failure” which leads to an “overly simplistic criticism of organizations and managers for not exploiting learning opportunities”.

The existing modus operandi of learning from failure is more directed about post-incident of highly visible failures. These approaches, while still useful, are said to come too late for learning from failure and the “multiple causes of large failures are usually deeply embedded in the organizations where the failures occurred, have been ignored or taken for granted for years, and rarely are simple to correct”.

A key reason why organistions do not effectively learn from failure is their lack of focus on learning from small everyday failures – with a bias towards the big higher profile failures. They say that the little everyday failures are the early warning signs of impending disaster.

(** You can see the overlaps with the adaptive philosophies of learning from everyday/normal work)

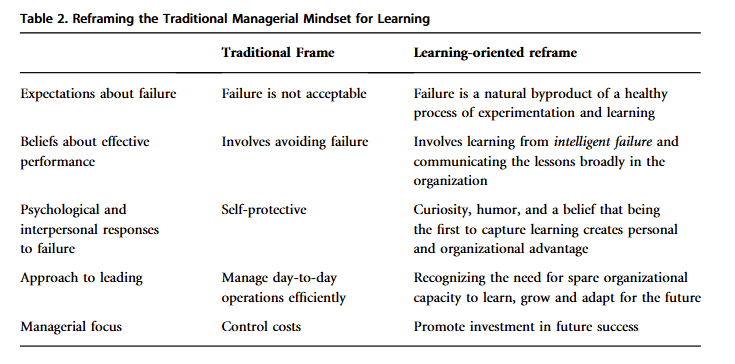

They’ve found that failing intelligently requires proactive identification and learning from small failures, and this requires different approaches, worldviews, structures and resources to achieve because they’re often overlooked as insignificant or isolated anomalies.

Hence, they’ve found “that when small failures are not widely identified, discussed and analyzed, it is very difficult for larger failures to be prevented”.

Barriers to organizational learning from failure

They say that learning from failure is a “hallmark of innovative companies”, but is “more common in exhortation than in practice”.

Most organisations are said to do a poor job of learning from failures – both big and small. They found that even when companies invested substantial resources into becoming ‘learning organisations’, they still struggled in the day-to-day mindset and activities of learning from failure.

Working against the learning organisation are “organizations’ fundamental attributes usually conspire to make a rational process of diagnosing and correcting causes of failures difficult to execute”.

Barriers Embedded in Technical Systems

Learning is said to be hampered by limitations in human intuition and sensemaking, since this leads to false conclusions. Factors include:

· A lack of scientific basis and know how in order to draw inferences from experiences systematically (e.g. how do we know something has had an actual observable effect)

· The opacity from complex systems, which obscure clear cause-effect relationships

Barriers embedded in social systems

Social barriers also make learning from failures challenging – as people naturally have a psychological reaction to the “reality of failure”. Social factors include:

· Being held in high esteem by others, is a strong human desire and “most people tacitly believe that revealing failure will jeopardize this esteem”

· Even though most people want to learn from failure and appreciate others’ disclosure of failure, pressures to maintain a positive public image provides a natural aversion to disclosing failure

· People also have an “instinctive tendency to deny, distort, ignore, or disassociate themselves from their own failures, a tendency that appears to have deep psychological roots”

· Also “Managers have an added incentive to disassociate themselves from failure because most organizations reward success and penalize failure”

· They argue that as a source of irony, the higher people are in the management hierarchy, the “more they tend to supplement their perfectionism with blanket excuses, with CEOs usually being the worst of all”

Quoting directly from the paper as they expressed this far more beautifully than I can:

· “Even outside the presence of others, people have an instinctive tendency to deny, distort, ignore, or disassociate themselves from their own failures, a tendency that appears to have deep psychological roots”

· “The fundamental human desire to maintain high self-esteem is accompanied by a desire to believe that we have a reasonable amount of control over important personal and organizational outcomes”

· “the positive illusions that boost our self-esteem and sense of control and efficacy may be incompatible with an honest acknowledgement of failure, and thus, while promoting happiness, can inhibit learning”

· “Managers have an added incentive to disassociate themselves from failure because most organizations reward success and penalize failure”

· And “holding an executive or leadership position in an organization does not imply an ability to acknowledge one’s own failures”

· “Ironically enough, the higher people are in the management hierarchy, the more they tend to supplement their perfectionism with blanket excuses, with CEOs usually being the worst of all”

· “Organizational structures, policies and procedures, along with senior management behavior, can discourage people from identifying and analyzing failures and from experimenting”

· “Many organizational cultures have little tolerance for – and punish – failure”

· “A natural consequence of punishing failures is that employees learn not to identify them, let alone analyze them, or to experiment if the outcome might be uncertain”

Even when failures are disclosed, “Most managers do not have strong skills for handling the hot emotions that often surface – in themselves or others – in such sessions”. These attempts to learn from failure can descend into scolding, finger-pointing or name-calling, where public or private embarrassment can leave people feeling sour.

Therefore, learning from failure “requires substantial interpersonal skill”.

Nevertheless, the barriers described above are “hard wired into social systems”, and therefore face almost every organisation to some degree.

Three processes for organizational learning from failure

They propose three activities to learn from failure: 1) identifying failure, 2) analyzing failure, and 3) deliberate experimentation.

Identifying failure

First organisations must identify the opportunities to lean from. However “one of the tragedies in organizational learning is that catastrophic failures are often preceded by smaller failures that were not identified as being worthy of examination and learning”.

Small failures are at risk of being denied, distorted or covered up.

Ways to improve here is leaders taking the initiative to develop systems and processes to bring the data to people so the failures can be identified.

They provide some suggestions (like from healthcare and interpreting mammograms), which I’ve skipped. But feedback seeking is another way of learning, with formal and informal mechanisms to receive feedback from clients, customers, suppliers, staff etc. They provide an example that just 5-10% of dissatisfied customers choose to complain about service failure in some areas, and most just switch providers.

Failing to identify failures

They provide the example of the Columbia shuttle accident. NASA managers “spent 16 days downplaying the possibility that foam strikes on the left side of the shuttle represented a serious problem – a true failure – and so did not view the events as a trigger for conducting detailed analyses of the situation”.

In hindsight, the strikes were “deemed ordinary events, within the boundaries of past experience”, and hence the opportunity to lean was lost. It’s argued that these psychological and organisational factors “conspire to reduce failure identification” and requires a reorientation and emotional task of seeking out failures.

Cultures that promote failure identification

They argue that organisations should create an environment where people have an incentive to identify and reveal failure to leadership, or at least, “do not have a disincentive”.

They provide another healthcare example about a blameless reporting system.

Analyzing failure

After identifying failure, organisations need to test ways to analyse them for learning opportunities.

Lots of means exist here. They provide examples, like after-action reviews and the like. A challenge here is that undertaking an analysis/investigation takes a “spirit of inquiry and openness”, and also patience and tolerance for ambiguity. Yet, “most managers admire and are rewarded for decisiveness”, of which these competing logics can impact a deep reflection of failure.

Moreover, “People tend to be more comfortable attending to evidence that enables them to believe what they want to believe, denying responsibility for failures, and attributing the problem to others or to ‘the system”.

They cite evidence from a large European telecoms company. This study found that “very little learning occurred from a set of large and small failures over a period of twenty years”.

Instead of learning and thorough analysis, “managers tended to offer ready rationalizations for the failures”. These failures were attributed to things outside of their control, like the economy, or influence of outsiders. Small failures were seen as flukes.

They argue for the need for formal processes or forums for unpacking failures and how these can be applied elsewhere. These groups need a mixture of skills, including technical skills, expertise in analysis and people skilled in conflict resolution and interpersonal skills more.

They provide examples of systematically analysing failure, which I’ve skipped.

Deliberate experimentation

Finally they talk about deliberate experimentation. Some organisations “not only seek to identify and analyze failures, they actively increase their chances of experiencing failure by experimenting”.

These organisations recognise failure as a necessary byproduct of experimentation – said to be “experiments carried out for the express purpose of learning and innovating”.

However, deliberate experimentation is said to be hampered by social systems, since success is normally rewarded and not failure.

They provide examples but I’ve skipped these.

In sum, they conclude:

· Although many technical and social barriers exist hampering learning, organisations can overcome these barriers to some degree with thoughtful action

· They can also break down learning into constituent activities and then track how they learn

· “While catastrophic failures will always, and rightly, command attention, we suggest that focusing on the learning opportunities of small failures can allow organizations and their managers”

· Failure shouldn’t be viewed as a problematic aberration that must always be avoided but instead as an inevitable aspect of operating in a complex world

· However, this doesn’t mean aiming for major failure, nor avoiding holding people accountable “but for failing intelligently, and for how much they learn from their failures”

· One can identify intelligent failures by: 1) they result from thoughtfully planned actions, 2) have uncertain outcomes, 3) are of modest scale, 4) are identified or responded to with alacrity, 5) are facilitated by mechanisms of effective learning

· In contrast, examples of unintelligent failures include making the same mistake over and over, failing due to carelessness, or not properly conducting experimental learning

Cannon, M. D., & Edmondson, A. C. (2005). Failing to learn and learning to fail (intelligently): How great organizations put failure to work to innovate and improve. Long range planning, 38(3), 299-319.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2005.04.005

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/failing-learn-learning-fail-intelligently-how-great-put-hutchinson-y2n1c