This conference paper briefly discussed the follies of lower order controls in the context of human performance.

Nicely, it took a really empathetic view of people and their limits in perception and attention: it’s not a bug that needs to be blamed or feared, but just a biological feature which needs to be considered.

First they provide a brief background on the hierarchy of control (HoC), including its history and various guises. Some sources describe it via 5 levels, whereas other sources have 9 levels.

In any case, they all share the principle that, independent of the number of controls, approaches to eliminate or reduce risk in design, and redesigning the work environment is more effective than “measures dependent on human behavior to recognize hazards and comply with safe work practices”.

A strength on elimination, substitution and engineering controls is that they “reduce dependence on controls that rely on real time knowledge and action of employees in management and supervisory roles, as well the workers that are exposed to the hazards”.

Lower order controls often depend on “workers’ attention to recognizing hazards and doing the right thing at the right time to avoid injury”. However, research suggests that “it is simply not possible for a human being to focus attention at all times and sustain attention for long periods of time”

Importantly, the authors argue that these:

“limitations of attention are not flaws in human behavior; it is a natural process of being human. To think otherwise is a misunderstanding of human nature that puts workers at risk”

Different global / regulatory approaches to risk management

Next they cover some different regulatory approaches in managing risk. For instance, some research has found that the occupational fatality rate in the US is three times higher than the UK, and the US construction industry fatality rate four times the UK’s rate.

Fatality rates due to contact with electricity is 3.8 times higher in the US than the UK.

[** Note there’s a lot of depth to these sorts of comparisons – including differences in industries, demographics, regulatory frameworks, climates, cultures etc.]

Some work has argued that one key difference in the UK and Europe, compared to the US, is the “regulatory emphasis on risk assessment and rigorous application of a hierarchy of controls as a likely significant factor”.

It’s argued that the US strategy for improving workplace safety has focused more on product standards, codes, safe work practice, regulations and standards. As such, this approach “has placed greater dependence on Lower Order Controls”.

According to the author, there is increasing awareness in the US that their fatality rate is significantly higher compared to countries which regulations place greater focus on risk assessment. This includes use of the HoC.

Example of the HoC

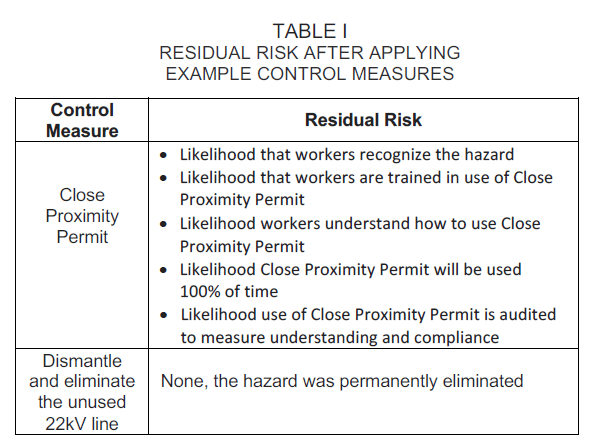

The authors give an example of managing electrical risks. I’ve skipped a lot of this example and can’t even remember what the point of this section was. But briefly: an electrical substation is located along the perimeter fence of an equipment storage yard. This yard has fork trucks and plant operating within the yard, with a risk of contacting the overhead line connecting with the substation.

The yard contacted the electrical entity and had a redundant 22 kV line removed. Hence, risk of contacting this line was now eliminated.

However, removal of the 22 kV line by the linespeople did involve risks. However, “the risk associated with the removal were assumed by the utility organization and their employees”.

This risk treatment option—eliminating the overhead line—therefore transferred risk to another party.

This risk transfer was seen to be acceptable, for several reasons: 1) once the hazard was removed, the associated risk was permanently eliminated, 2) the risk associated with removing the line was transferred to another party with more experience in managing the electrical hazard.

The authors says that just as the yard owner’s workers used lower order controls to manage the risk of overhead contact (procedures and the like), the electrical entity’s workers likely used lower-order controls to remove the electrical hazard. However, it could be argued that the linespeople, even though using lower order controls, are far more experienced and accustomed to this specific hazard.

In any case, they say that in this day and age being able to completely eliminate electrical hazards is rare. So more often the goal should be to modify the design so that the likelihood of human error, severity of consequences, and the need for PPE is “at a practical minimum”.

Human Factor Limitations of Lower Order Controls

Next the paper discusses the folly of relying too heavily on lower order controls, in the context of human performance.

Quoting the paper, “Research by Dekker and others has shown that it is inevitable that people will make mistakes in judgement and behavior that can lead to injury, even though they may be highly competent, qualified and conscientious”.

So even qualified and highly competent people do sometimes get injured, and this can occur in ways that, in hindsight, their expertise could have prevented but didn’t.

Lower order controls, like warnings, admin controls/rules and PPE, require “conscious effort and action on part of administration, supervisors, and workers”. This requires, in part, people to “pay attention for the control to be effective”.

Warnings for example, require people to see the sign, consciously process the information on the sign, and then determine that the sign is worth heeding.

Admin controls require that management take the time and cost to train and instruct workers, and provide them the cognitive bandwidth to heed the controls.

PPE requires that management have provided the right PPE to the right people, at the right time, and that the PPE suits their goals, know how to use it, and be alert and attentive enough during their shifts to recognise when they should use it.

Attention and human performance

A basic definition for attention is a person’s capacity to select and process information. It falls into: 1) focusing – which is selecting what objects to attend to, and 2) concentrating – which is holding that attention for an extended period of time.

While many different models and constructs of attention exist in psychology, most are underpinned by the idea that “our cognitive capacity for attention is limited due to a limited amount of brain resources”

People simply can’t pay attention to everything, all the time, all at once, in their environment. This is why the brain developed means to shed cues and data in order to select objects to pay attention to and to concentrate on.

Sustained attention

Sustained attention is concentrating on one thing for an extended period of time. A 1978 study looked at sustained attention of >1.3k medical students. They found that the medical students’ attention “reached a maximum about 10-15 minutes into a class lecture, and decreased from 15 minutes onward”.

Further, the longer people try to sustain attention on one thing, “the slower they are to respond to changes in their environment”. One review study found that working on tasks for longer than 60 minutes slowed reaction time by several hundred milliseconds. As an example, “a delay as small as 100 milliseconds translates to a stopping difference in 10 feet for a driver traveling 70 miles per hour”.

Inattentional Blindness

Inattentional blindness describes where people can look at something but not see it.

Like, you look for your keys which are right in front of you but you fail to see them.

The authors dispels the myth that people missed something because they simply didn’t look hard enough. Namely, research using eye tracking has found that people can look directly at an object and not process what they are seeing.

Cognitive tunnelling is a related phenomenon, where people can focus so much on one object that they “lose awareness of the broader environment surrounding them”.

Both inattentional blindness and cognitive tunnelling have implications for safety. One study found that 76% of employees at a large state university didn’t know the correct location of their nearest fire extinguisher, even though the employees walked past it on a daily basis (and where the average tenure in that university was 5 years).

Importantly, phenomenon like inattentional blindness and cognitive tunnelling “are not flaws of human attention but are symptomatic of normally functioning cognitive systems”.

Quoting Reisberg on inattentional blindness, it’s said that “these cases of [inattentional blindness] failing-to-see are entirely normal.”

Conclusion

Wrapping up, the authors suggests the following:

· Limits of attention aren’t flaws in human behaviour but are characteristics of normal cognitive functioning [** e.g. you can’t simply will, prescribe or train them away]

· Reaction time slows after long periods of sustained attention

· Inattentional blindness means people can look directly at object but not consciously ‘see’ them

· People can place so much focus on one object that they lose awareness of their larger surroundings

· Understanding human performance can help to design better work environments, prioritising higher order controls and design principles

Ref: Floyd, H. L., & Floyd, A. H. (2017). Residual risk and the psychology of lower order controls. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, 53(6), 6009-6014.

Study link: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8025426

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/residual-risk-psychology-lower-order-controls-ben-hutchinson-rmjtc