A 2002 paper from Andrew Hale talking about fatal vs non-fatal, minor vs major incidents, and the (then-known) links between them, if any.

A lot of this paper focuses on Heinrich’s work and the jank interpretations and myths that have developed over time, inconsistent with Heinrich’s intentions.

There’s newer and more thorough discussions of these interpretations, so I’m not covering Hale’s arguments too deeply, and will focus on other stuff in the paper.

In any case, Heinrich was said to be the “first proponent of the similarity of causes of minor and major accidents and summarised his conclusions in his triangle”, which has been “endlessly copied ever since”.

Hale argues that an interpretation of the triangles are that:

1. “There were many precursors to disabling accidents, if one looked closely enough at an activity” and it’s therefore “not necessary to wait until that accident … in order to start on prevention”. No disagreements from Hale on this

2. There’s many more minor than major incidents

3. The causes of major and minor incidents (damage, injury) are the same. This third point is that which Hale covers the most in this paper.

Interestingly, on point 3 he observes that “It is not so much Heinrich himself as his followers who drew this conclusion in a black and white way”.

I’ve skipped a lot of the reasoning and argumentation around the jank interpretation of Heinrich’s work. But one conclusion for Hale is the “strength of the belief in identical causes of major and minor accidents which, subsequent to Heinrichs original work, grew up among safety practitioners, and apparently also among researchers”.

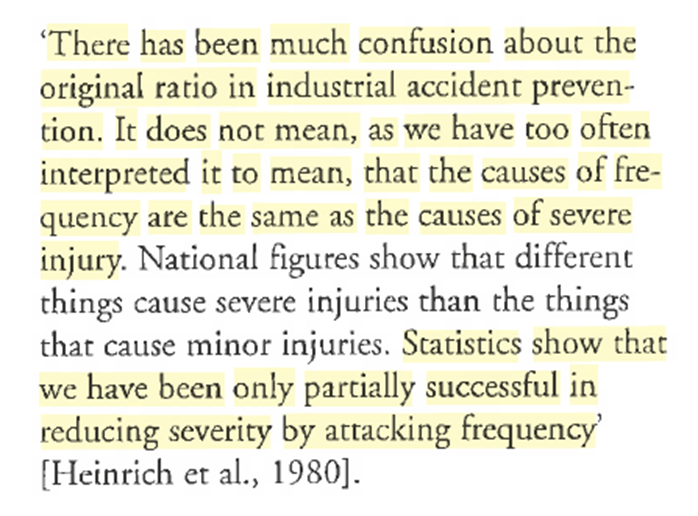

Furthermore, in the 1980 5th ed of Heinrich’s book, it was even remarked that:

Hale argues that it’s a persistent urban myth that seems plausible and commands “immediate acceptance without proof”.

One factor may be because minor incidents occur frequently, so efforts to reduce them are visible, whereas major events are statistically rare.

Hale covers the then-current research on the links between minor and major. This part has aged of course, since we have a lot newer research. But as of 2002:

1. One study in Salminen 1992 argued for identical causes of minor vs major, and two others for different causes

2. Finnish research in 1998 showed that fatal accident and lost time injury rates at company and national levels “showed opposing trends over time”, e.g. as one goes up, the other goes down

3. A 1993 study found little correlation between loss of containment chemical incidents and the frequencies of occurrence of incidents. They also concluded that “lost time injuries (LTIs) could not be used in any way as indicators of major hazard safety for a plant”

4. One of my favourite quotes comes from this paper, where Hale states “We are not going to get very far in preventing major chemical industry disasters by encouraging people to hold the handrail when walking down stairs”

Hale covers a few more studies arguing in both favour of or against a connection between minor and major. There’s newer work here (recommend reading Bayona’s 2024 article ‘The things that hurt people are not the same as the things that kill people’, which covers newer research – link to my summary in comments).

Lessons from Major Accident Investigations

Hale briefly touches upon some major accidents like Piper, Challenger, Bhopal, Three Mile Island.

Namely, “we are always struck by the fact that there were signals of impending disaster long beforehand”, e.g. misuse of permit systems, limited O-ring burn through, failure of sprinklers and more. Though, always clearly evident in hindsight.

Hale argues that many of these examples are more examples of ‘near misses’, or at least, issues with planned defences, rather than incidents.

He argues that it’s not so much the occurrence of the damage that’s interesting, but:

“the fact that the scenario is the same, which teaches us the lesson. The conclusion I wish to draw from all this is that: major accidents can sometimes be predicted by minor accidents, but not always; that there are always near misses and deviations, which are precursors of major accidents; and that not all minor accidents could have been major accidents”.

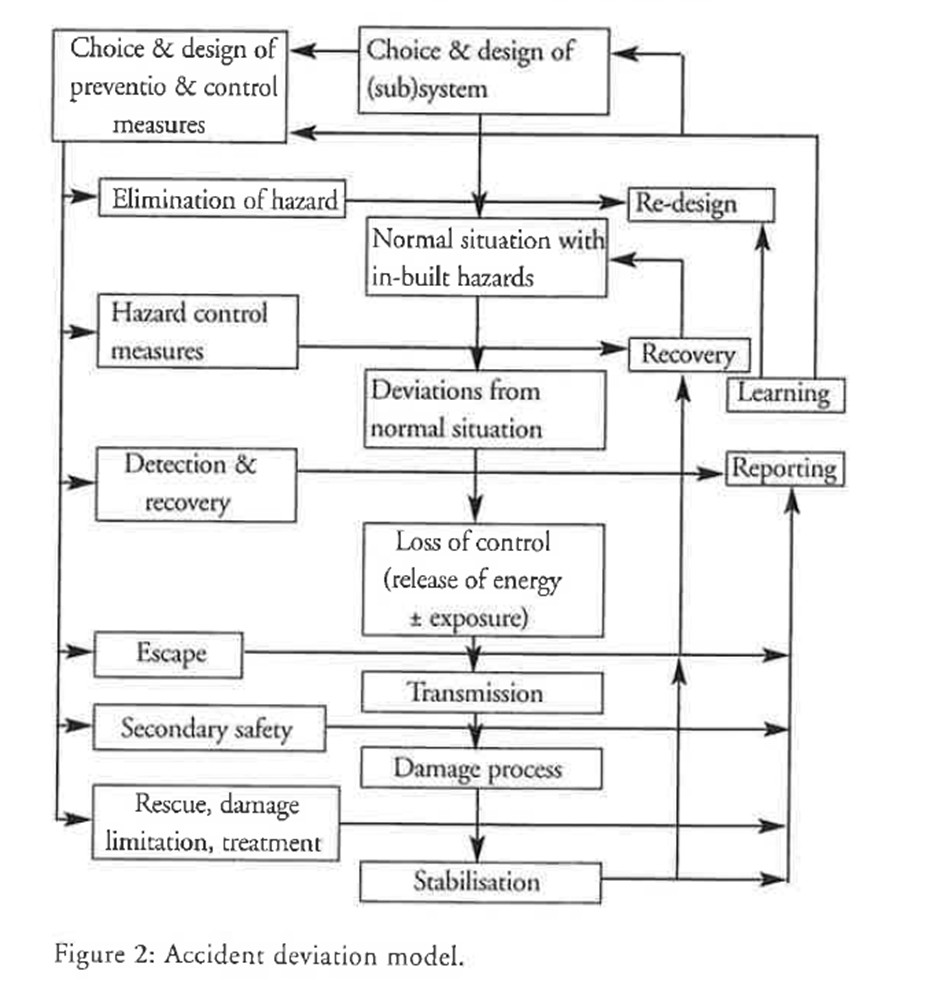

Next Hale talks about a ‘deviation model’. He observes how Heinrich’s work looked back from a single disabling injury, finding it occurred much more frequently on other occasions.

And hence, “There is an important truth in this way of looking at an issue”. That is, incidents result from the culmination of a process [** systems people may argue from the interactions, but whatever], and that the incident trajectory, in theory, could be stopped at a number of points.

This is shown below:

Hale makes another few arguments which I’ve skipped, but in all he suggests that we can generate specific ‘pyramids per scenario’. He must also focus on precursors.

So, looking at particular scenarios is fruitful, and aligns with Heinrich’s work, and “it is when we combine the pyramids into one great one that the logic goes sour”.

[*** Interestingly, Bellamy’s 2015 study based on >12k serious Dutch accidents came to the same conclusions: there can be a connection between minor and major severity events provided we’re dealing with the same accident scenarios; the connection is the hazard itself. Check out episode 4 of Safe AF podcast]

Hale says there’s another danger if different scenario pyramids aren’t distinguished: measures to control one sequence may adversely impact another sequence. A nuclear facility in Japan introduced new uranium containers to reduce physical workload and back injury, but now concentrated greater radiation dose to the handlers.

Hence, “Recovering from a minor injury scenario opened the way for a deviation path leading to a fatal accident”.

Based on the deviation model, different questions result:

1. Is there enough energy involved that the damage will be great if the sequence progresses to completion?

2. Will the sequence get as far as the damage, or be diverted by a recovery mechanism

a. If diverted, will the mechanism reduce the potential from major to minor

Humans are naturally variable in their performance, and can respond well to deviations (though, not always of course – as several major accidents indicate).

Nevertheless, “we cannot and should not try to prevent all deviations. We should try only to prevent those which will not be detected and recovered” [** Remember, this isn’t talking about procedural deviation or something else, it’s talking about via the process model above]

Defences In Depth

Hale finishes with defences in depth and auditing.

On defences in depth, “The more carefully constructed the barriers which are in place, and maintained, the less chance that the accident sequence will progress to its ultimate damage stage”.

But organisations need to have a clear view of all potential scenarios and be able to distinguish the major from minor ones, in order to better focus resources and efforts.

And here, “The importance of the debate on the similarity of causes between major and minor accidents lies in this danger. If companies think the causes are the same and they are not, they are betting on the wrong horse (and vice versa)”.

Auditing & Complexity

While barrier / defences in depth are well intentioned, a “A danger of a sophisticated defence-in-depth strategy is its complexity”.

Hence, people can “see less and less clearly what aspects contribute to controlling what scenarios, unless this is clearly documented”.

And this is a phenomenon they have observed in high risk organisations which sophisticated safety systems – a lack of clarity on the connections.

It’s argued that this lack of clarity is “particularly dangerous where the company wants to scrap or simplify parts of the system, or to eliminate staff from the company”.

They highlight the false safety from an audit. The audit structure was based on a generic checklist for assessing 8 critical resources for risk management. It was suitable for this task. But, without more precision on the crucial scenarios or tasks of major incidents, it provided little value or substance.

Therefore, “Without this focus it was easy for the company co tell a convincing generic story about management systems which were present, but which were probably only working for minor accident scenarios”.

Conclusion

In all, Hale argues that “Too many people working in safety seem to believe unquestioningly that the causes of major and minor injury are similar”.

For one, while “At a management level the causes may be similar at a generic level of categorisation”, they’re not similar at a detailed level (as of the research in 2002).

In any case, Hale cautions that instead of thinking in terms of comparing minor and major, we should instead better understand accident scenarios.

We should compare completed vs uncompleted accident sequences, and how this informs on what is working or not working.

And finally, “we should understand that, although the broad structure and functioning of management systems for major and minor hazards (and for health, environment and quality) may be the same, what we do in detail under those generic headings must be scenario-specific”.

Ref: Hale, A. R. (2001). Conditions of occurrence of major and minor accidents. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 5(1), 7-20.

Shout me a coffee (one-off or monthly recurring)

Study link: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313141896_Conditions_of_occurrence_of_major_and_minor_accidents

Safe AS LinkedIn group: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/14717868/

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/conditions-occurrence-major-minor-accidents-urban-myths-hutchinson-l8o0c