Really interesting discussion paper on the premise of ‘botshit’: the AI version of bullshit.

I can’t do this paper justice – it’s 16 pages, so I can only cover a few extracts. Recommend reading the full paper.

Tl;dr: generative chatbots predict responses rather than knowing the meaning of their responses, and hence, “produce coherent-sounding but inaccurate or fabricated content, referred to as hallucinations”. When used uncriticually by people, this untruthful content becomes botshit.

They cover some prior research showing some benefits of chatboys, like improving colleague students’ writing productivity and quality. The initial excitement of such a technology in our own consumer hands led “ChatGPT [to] become the fastest-growing consumer application ever, achieving 100 million users within 2 months”.

This rapid uncritical adoption has its risks. Like:

· “LLMs are great at mimicry and bad at facts, making them a beguiling and amoral technology for bullshitting”.

· Chatbots “predict responses rather than know the meaning of these responses”, where chatbots are likened to “stochastic parrots … as they excel at regurgitating learned content without comprehending context or significance”.

· These LLMs predict patterns but “lack inherent knowledge systems like the scientific method to evaluate truthfulness”. They can also hallucinate responses that are unsupported by their training data.

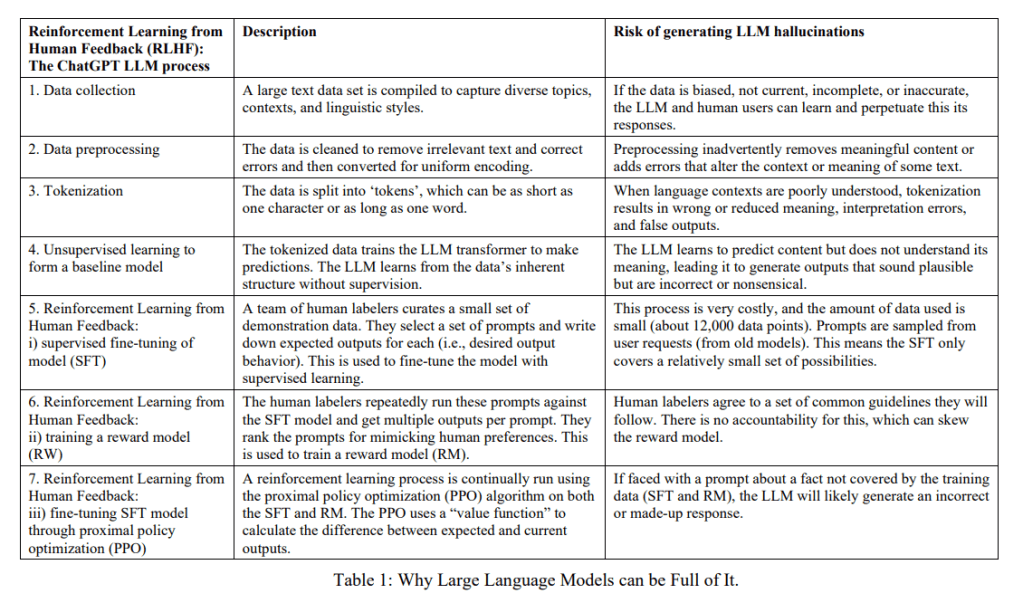

They discuss how LLMs can generate botshit – I’ve skipped all of this, but it’s captured in the below table:

In any case, chatbots are “powerful content generation and analysis tools”. They can as a research assistant, data analyst or co-author, in a “conjoined agency approach”. This approach leverages chatbots with careful precision. However, chatbots in and of themselves have no sense of truth or reality “beyond the words that tend to co-occur in their training data and processes”.

In their view, to use LLMs responsibility, we need to understand the epistemic risks introduced by this tech. “Epistemic risk is the likelihood that one’s claims inaccurately represent the world”.

They provide several insights at different steps of the LLM processing chain where inaccurate content can be generated.

Ideally, LLMs would have some way to baseline against “ground truths”, in their words which are “actual, definitive, and accurate data against which the LLM’s predictions or outputs are compared”. But this isn’t always possible.

Like, who invented product X could have a clear and definitive response, whereas who is the leading practitioner in domain X likely doesn’t.

In all, they argue that “generative chatbots are not concerned with intelligent knowing but with prediction”. In saying that, they recognise that LLMs can be trained to predict content that will be useful and credible.

However, this isn’t based on an “intelligent context-based response”, but is rather a “technical word salad based on patterns of words in training datad which is itself a black box”.

Therefore, chatbots excel at “predicting how to make stuff up to prompts, which sometimes turn out to be correct”.

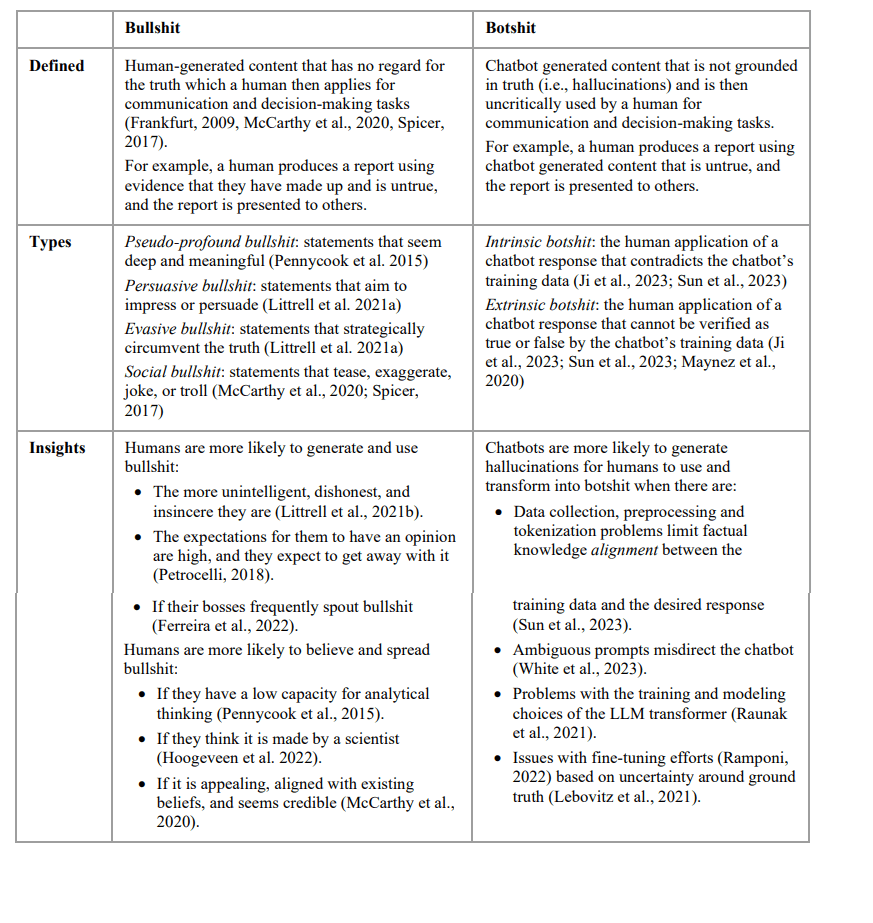

Bullshit and botshit

Next the authors expand on the concept of bullshit, noting there’s different kinds. Bullshitting is when somebody generates content not grounded in truth, and then uses it for a form of social, persuasive or evasive agenda.

BS isn’t lying – since lying implies somebody knows the true state of affairs (** so far as we can make that claim of ‘truth’).

Bullshitting is somebody who has no concern, an indifference, to the truth and isn’t constrained by it.

LLMs hallucinate when they generate “seemingly realistic responses that are untrue, nonsensical, or unfaithful to the provided source input”. LLMs aren’t lying, since they have no intrinsic motive to deceive, nor know the meaning of their responses.

They delineate different kinds of bullshit and botshot:

Pseudo-profound bullshit are statements wrapped in deep or meaningful auras, but lack depth or substance on closer examination. It’s said to rely on “obscure or vague language to create an impression of wisdom or significance”.

They give an example of the Starbuck’s CEO who said they deliver an immersive, ultrapremium coffee-forward experience.

Bullshit can be persuasive or evasive in nature. Persuasive involves embellishing or stretching the truth to persuade, often using vacuous buzz words.

Evasive bullshitting is a “strategic circumvention of the truth”, involving statements to avoid revealing that you don’t know something.

Humans and bots produce BS for different reasons, of course. Humans are often motivated by social or professional motives and when the bullshitter doesn’t except the veracity of their claims to be checked.

LLMs “should not possess intentional motives or deception agendas” but their BS derives from inherent limitations of AI and LLMs.

Bullshit and botshit are likely to be more believable when they satisfy three criteria:

1. If it is useful, beneficial or energising for the audience

2. If it aligns with and flatters the audiences’ interests, beliefs, experiences or attitudes

3. If it is perceived to have some credibility based on how articulate it is – riddled with jargon and all

Number 3 is similar to the Einstein Effect, where we are “more likely to believe a bullshit statement if we think it is made by someone with prestigious, scientific standing”.

A typology of chatbot work modes

The authors suggest practitioners apply two questions for their use of LLMs and similar tech:

1. How important is the chatbot response veracity for the task?

2. How easy is it to verify the veracity of the chatbot response?

Expectedly, when the “When the risk severity of using chatbot content for work is catastrophic, chatbot response veracity is crucial amid high-stakes investment decisions, mission-critical operations activities, and situations with low or zero tolerance for failure (e.g., equipment maintenance, patient well-being”.

When the risk is low of using inaccurate chatbot content, like ideas for brainstorming, then veracity is less important. E.g. “if a chatbot is used for a task that is cheap and easy to reverse, or if the effects of hallucinatory content are trivial”, then the potential costs of false info is low.

There will also be many instances when the chatbot claim veracity can’t be verified.

Using chatbots with integrity

They outline some principles of using chatbots with integrity:

1. users should be aware that each mode comes with a specific epistemic risk: these risks should be matched by processes and practices to manage such risks for critical applications

2. Ignorance is likely the key risk for augmented mode of chatbot work, where users overlook or are unaware of the LLMs harmful outputs

3. The key risk that comes with authenticated chatbot work mode is that users may miscalibrate the value of chatbot responses for their work, e.g. overrelying on the responses or believe that the responses have more veracity and value than human work

4. The key risk of autonomous mode of chatbot work is understanding the extent of the chatbot blackbox (e.g. the inner workings of the chatbot aren’t fully understood or accessible to the user)

a. Users often don’t know or care how the tech does its magic, so let it go about its task uncritically

5. Automated and autonomous chatbot applications requite the most sophisticated, fixed and strongest organisational interventions/guardrails to constrain the LLM performance

They cover a lot more but I’ve skipped this.

Ref: Hannigan, T. R., McCarthy, I. P., & Spicer, A. (2024). Beware of botshit: How to manage the epistemic risks of generative chatbots. Business Horizons, 67(5), 471-486.

Shout me a coffee (one-off or monthly recurring)

Study link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm?abstractid=4678265

Safe As LinkedIn group: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/14717868/

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/beware-botshit-how-manage-epistemic-risks-generative-ben-hutchinson-frfhc