A 2001 article from Sid Dekker discussing a contemporary view of human performance and organisational failure.

You may recognise parts of this from Dekker’s later article ‘Is it 1947 yet?’.

Too much to cover. And I’m relying heavily on quotes.

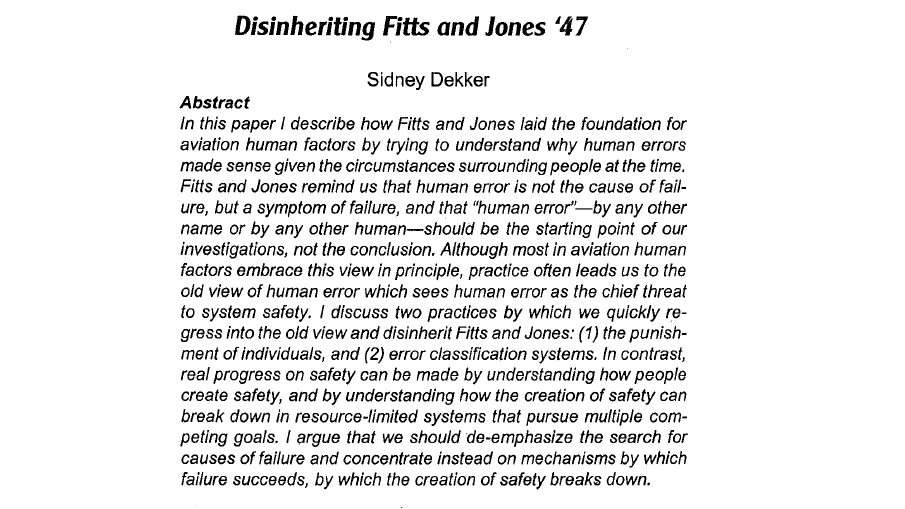

Dekker reverts back to Fitts and Jones’ 1947 article which “laid the foundation for aviation human factors by trying to understand why human errors made sense given the circumstances surrounding people at the time”

Tl;dr:

· error isn’t the cause of failure but rather a symptom;

· error, however it’s titled, should be the start of the investigation and not the conclusion;

· we need to move beyond blame; and

· we should “de-emphasize the search for causes of failure and concentrate instead on mechanisms by which failure succeeds, by which the creation of safety breaks down”.

Fitts and Jones aviation report unpacked how WW2 airplane cockpits “systematically influenced the way in which pilots made errors”, like where pilots confused the flap and gear handles, mixed up throttles and other controls and other factors.

For these authors, “Human error was the starting point … [and] The label “pilot error” was deemed unsatisfactory, and used as a pointer to hunt for deeper, more systemic conditions that led to consistent trouble”.

When we dig deeper, “mistakes actually make sense once we understand features of the engineered world that surrounds people”. Moreover, error is “systematically connected to features of people’s tools and tasks”.

That insight, profound back then as it still is now, highlights that: “the world is not unchangeable; systems are not static, not simply given”.

We can thus change the environment to influence the way people work; being the basis of human factors so we can understand “why people do what they do so we can tweak, change the world in which they work and shape their assessments and actions accordingly”.

Aerospace HF was said to later extend Fitts and Jones’ work, recognising how “trade-offs by people at the sharp end are influenced by what happens at the blunt end of their operating worlds”.

Organisations create a continual tension: they make available resources for people to use in their workplaces (e.g. tools, training, teammates”, but at the same time “put constraints on what goes on there … (time pressures, economic considerations), which in turn influences the way in which people decide and act in context”.

Two Views Of Human Error

Next Dekker covers two views on human error.

The first sees human error as a cause of failure, the second sees error as a symptom of deeper failure.

These two views had been previously referred to as the old view of human error versus the new view.

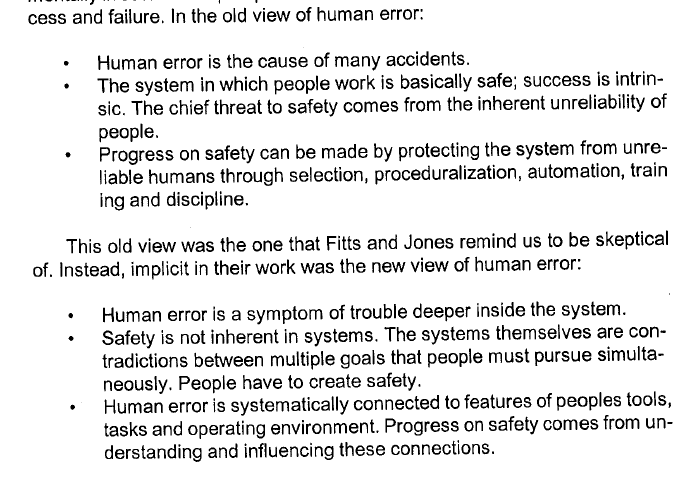

Quoting the paper, in the old view of human error:

· “Human error is the cause of many accidents”

· “The system in which people work is basically safe; success is intrinsic. The chief threat to safety comes from the inherent unreliability of people”

· “Progress on safety can be made by protecting the system from unreliable humans through selection, proceduralization, automation, training and discipline”

Dekker argues that this old view of human error is the type that Fitts and Jones “remind us to be skeptical of”.

Instead, Dekker argues that their work advocated for the new view of human error, again quoting the paper:

· “Human error is a symptom of trouble deeper inside the system”

· “Safety is not inherent in systems. The systems themselves are contradictions between multiple goals that people must pursue simultaneously. People have to create safety”

· “Human error is systematically connected to features of peoples tools, tasks and operating environment. Progress on safety comes from understanding and influencing these connections”

It’s argued that while pursuing the new view, we can often retread the old view. For instance, Dekker argues that replacing the tendency to blame with explaining “turns out to be difficult”. We also can’t easily avoid the fundamental attribution error; and tend to “blame the man-in-the-loop”.

Most people probably don’t intend to blame and indeed want the opposite. However, “roads that lead to the old view in aviation human factors are paved with intentions to follow the new view”.

The Bad Apple Theory

Next the bad apple theory of human performance is discussed. This is aligned with the old view of human error, where we try to weed out the pesky unreliable human performance, use of training, and “tweaking the nature of human attributes in complex systems that themselves are basically safe and immutable”.

Hence, the inherently safe system contains bad apples, and we need to control or remove the bad apples to maintain safety.

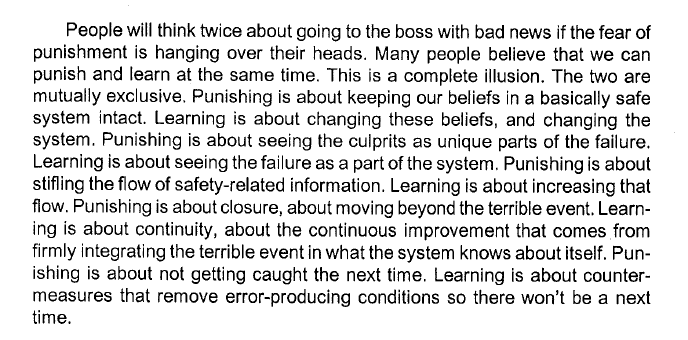

This also leads to blame and punishment. Dekker argues that “Fear as investment in safety” is a “bizarre notion”. The scientific opinion is pretty clear on how to learn from failure: “fear doesn’t work”.

Instead, fear “corrupts opportunities to learn”. Fear “does the opposite of what a system concerned with safety really needs”, which is learning before accidents occur. Therefore, fear stifles safety intel, ensuring it doesn’t reach senior leaders. For example, people will think twice before taking bad news to their boss if they think they’ll be punished.

Moreover, “Many people believe that we can punish and learn at the same time”, but in Dekker’s opinion “This is a complete illusion”.

Learning and punishment are “mutually exclusive”, since:

· Punishing focuses on maintain our beliefs of a basically safe system, whereas learning is about changing these beliefs and improving the system

· Punishing focuses on identifying culprits as part of failure whereas learning sees “failure as a part of the system”

· Punishment stifles the flow of safety intel whereas “Learning is about increasing that flow”

The Construction Of Cause

Next Dekker talks about whether incident causes are found or constructed. The old view of human error believes that causes can be found out there in the world “neatly and objectively, in the rubble”.

In Dekker’s view, the opposite is true: “We don’t find causes. We construct cause”. If we were to trace “the cause” of failure, the “causal network would fan out immediately”.

Indeed, it would be more like cracks in a window, with only the investigator “determining when to stop looking because the evidence will not do it for him or her. There is no single cause. Neither for success, nor for failure”.

Next Dekker talks of local rationality – and how Fitts and Jones’ insights were “right all along”. Local rationality highlights how “People do reasonable, or locally rational things given their tools, their multiple goals and pressures, their knowledge and their limited resources”.

Therefore, “human error” is a symptom of “irreconcilable constraints and pressures deeper inside a system”, a signal of systemic trouble upstream. For Dekker, therefore, “Human error is uninteresting in itself”. Rather than being a separable category of unexpected sub-standard behaviour, it’s a post-hoc label applied to “fragments of empirically neutral, locally rational assessments and actions”.

Human Error and Classification

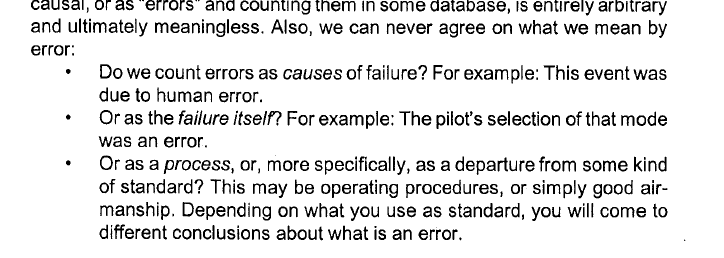

Next Dekker takes aim at error classification approaches. I’ve skipped heaps, but he says one trap in studying errors is confusing classification with analysis. Classification systems, in his view, tend to “risk trotting down a garden path toward judgments of people instead of explanations of their performance”.

Error classification approaches also assume that we can make meaningful sense of count and tabulated data on errors. In his view, error “in the wild’ … occurs in natural complex settings-resists tabulation because of the complex interactions, the long and twisted pathways to breakdown and the context-dependency and diversity of human intention and action”.

Also, we rarely clarify what we mean by error. Is it the cause of failure, is it the failure itself, is it the process or departure from some standard? Hence, in Dekker’s view, “Counting and coarsely classifying surface variabilities is protoscientific at best”.

The old view of human error also highlights the problems of counterfactual reasoning for making sense of the decisions and actions of people caught up in an event. That is, “it is counterproductive to say what people failed to do or should have done, since none of that explains why people did what they did”.

Error classification approaches instead of explaining why people did what they did instead capture insights as “poor decisions” or “failures to adhere to…” sorts of statements. These “are not explanations, they are judgments”.

He takes aim at judgements like loss of crew resource management or complacency, which are post-hoc judgments that masquerade as explanations. Per Fitts and Jones’ legacy, we “must try to see how people-supervisors and others-interpreted the world from their position on the inside; why it made sense for them to continue certain practices given their knowledge, focus of attention and competing goals”.

People Create Safety and When Failure Succeeds

We can “make progress on safety once we acknowledge that people themselves create it, and we begin to understand how”.

That is, safety isn’t an inherent part of systems, nor is it introduced in isolation via technical or procedural fixes. Instead, Dekker argues that it’s people that create safety across all levels of an operational system. So, “Safety (and failure) is the emergent property of entire systems of people and technologies”.

Conversely, a problem occurs “when failure succeeds”. That is, “People are not perfect creators of safety”. Therefore, there are “patterns, or mechanisms, by which their creation of safety can break down-mechanisms, in other words, by which failure succeeds”.

So how does failure succeed? Dekker covers a few areas of major complex failures, mostly high-level concepts like normalisation of deviance, going sour, practical drift, and plan continuation bias.

In any case, Dekker argues that there’s “no quick safety fix” for understanding human performance, and always the risk of a “retread of the old view”. Punishing culprits doesn’t help unpack the multiple competing goals in our resource-constrained organisations.

In saying that, though, Dekker argues more optimistically:

“There is, however, percentage in opening the black box of human performance-understanding how people make the systems they operate so successful, and capturing the patterns by which their successes are defeated”.

Ref: Dekker, S. (2001). Disinheriting Fitts and Jones’ 47. International Journal of Aviation Research and Development, 1(1), p7-18.

Shout me a coffee (one-off or monthly recurring)

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2022.105986

Safe As LinkedIn group: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/14717868/

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/disinheriting-fitts-jones-47-ben-hutchinson-3tppc