How are barriers/risk control systems undermined by systemic issues?

This 2004 study unpacks a few mechanisms of how barriers are designed without a deep understanding of work constraints etc.

** Parts 2/3 in comments **

Not a summary – but a few cherry-picked extracts:

· “Because engineered systems increasingly incorporate forms of self-protection, operators have to monitor not just the primary function, but also the health of the device performing this function, and the devices that provide indications of the health of this device”

· “with greater automation operators are increasingly unpractised in operating a system – yet are only called on to deal with the system when the automation fails, typically when the system is in its most unpredictable and intractable state”

· “There are particular problems when automated controls attain high degrees of authority and autonomy. Such controls provide highly sophisticated technical functions, yet fail to provide adequate, basic feedback to human operators”

· “Norman’s (1992) work has shown how the design of devices and systems can cause problems more generally for their users – for example in failing to reveal important information about function, and failing to support the natural distribution of tasks among different people”

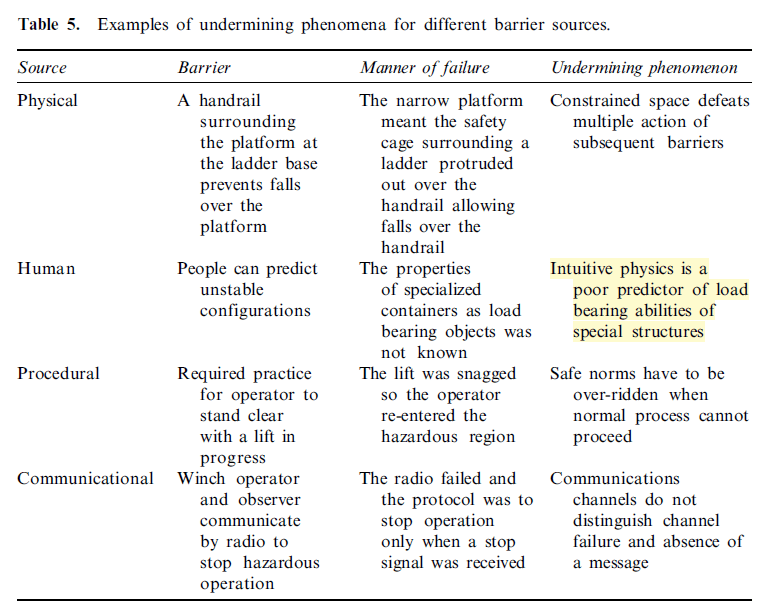

· Interestingly, barrier failures from “intuitive physics” are discussed

· Where operators applied their intuitive physics based in every day life, but “inapplicable to specialized industrial operations”

· But, rather than being a dispositional issue of the operator, it’s argued to see this as situational – “the design was also implicated because people’s failure to correctly assess the physics of equipment that is very different from everyday life experience is predictable”

· Drawing on Don Norman’s work, systems should help the operator to develop accurate mental models, using principles like affordances and signifiers

· “in several cases the barriers had a self-limiting quality, in that it was some characteristic of the barrier itself that led to its undermining”

· In one example, door action was slowed down to provide time for operators to get clear and avoid being crushed

· But, “in practice people found this slow action irksome, so only opened the door partially. Thus the latency intended by the designer did not, in reality, exist – and there was an accident in which an operator was crushed”

· “Wagenaar et al. (1990) refer to ‘escalation’ problems, where increasing barriers seem to be associated with increasing hazards in a kind of spiral. For example, stronger pressure vessels fail more catastrophically (although presumably less often)”

· “The problem seems to be that strong barriers do not signal the early development of failure, whereas weak barriers would provide such a signal because they would begin to fail and adverse effects would be noticed before the hazard became extreme”

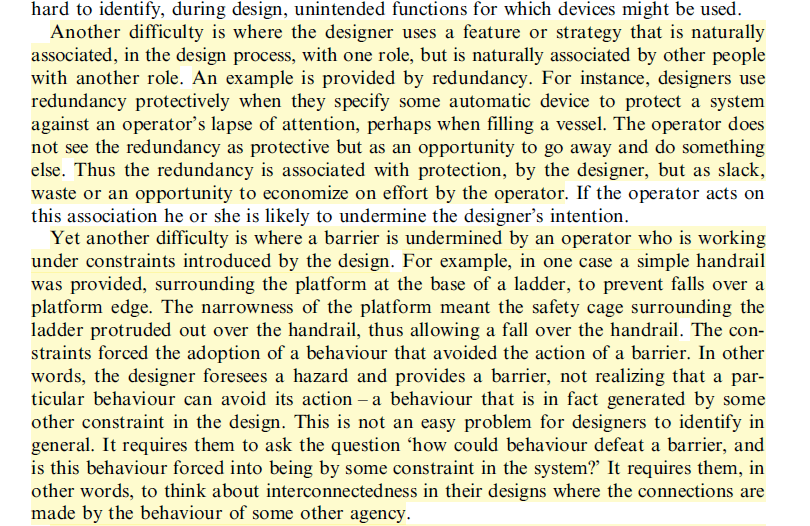

· Another challenge can be redundancy, where “designers use redundancy protectively when they specify some automatic device to protect a system against an operator’s lapse of attention, perhaps when filling a vessel”

· However, “The operator does not see the redundancy as protective but as an opportunity to go away and do something else”

· “Thus the redundancy is associated with protection, by the designer, but as slack, waste or an opportunity to economize on effort by the operator”

· “another difficulty is where a barrier is undermined by an operator who is working

· under constraints introduced by the design. For example, in one case a simple handrail

· was provided, surrounding the platform at the base of a ladder … [but] The narrowness of the platform meant the safety cage surrounding the adder protruded out over the handrail, thus allowing a fall over the handrail”

· “The constraints forced the adoption of a behaviour that avoided the action of a barrier. In other words, the designer foresees a hazard and provides a barrier, not realizing that a particular behaviour can avoid its action – a behaviour that is in fact generated by some other constraint in the design”

· It’s noted that this isn’t an easy issue for designers to address, but requires them to ask “how could behaviour defeat a barrier, and is this behaviour forced into being by some constraint in the system?

· “Engineering models can be highly sophisticated in the analyses they use to predict dynamics, but these models tend to link small numbers of variables in a limited domain (like the movement of solid bodies). They do not typically combine entities that exhibit qualitative complexity, like people’s behaviour in combination with climatic conditions”

· An issue of a failed radio channel was given. Simple in practice, but “the operator had no way of differentiating a channel failure from the absence of messages. This is a problem that is general to all kinds of communication system, such as alarms”

· It’s noted systems should a) provide feedback that they have failed (we found audit systems don’t often have these data – what we called “failing silently”), and b) fail in a safe state

· In rail for instance, signals have a fail-safe where they should have a ‘right-side failure’ (failing in a safe state, e.g. at danger, rather than wrong-side failure, failing in an unsafe state)

Ref: Busby, J. S., Chung, P. W. H., & Wen, Q. (2004). A situational analysis of how barriers to systemic failure are undermined during accident sequences. Journal of Risk Research, 7(7-8), 811-826.

Shout me a coffee (one-off or monthly recurring)

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1080/13669832000081196