This article discusses some of the mistakes or assumptions about human performance in complex environments.

Extracts:

· “Humans are not great at assessing risk. Engineers tend to be an optimistic lot, ready to solve any problem by relying on their technical skills and experience”

· And while it’s “incredibly tempting, in the relative calm of process hazard analysis (PHA) discussions … to assign near-superhero qualities to operations personnel for their ability to respond to upset conditions … the reality of … is almost always much messier and more complex”

· “There are several lies that we may tell ourselves when confronted with the need to identify and respond to worst-case scenarios”, like “I have never seen it, so it will not happen” or “This is just like that other time when …”

· “People are bombarded with information every minute of the day. There is a strong tendency to use individual experiences and knowledge as a short-cut in processing all this information—in other words, to interpret information in the context of what we expect to happen”

· “Risk assessment in the process industries is inherently an emotional activity. People are tasked with brainstorming the worst-case consequences within a process—the same process in which they spend a significant amount of their time every working day”

· Moreover, the team members usually do this task “in a conference room away from the hazards that they are discussing [in all] making it an even more sterile environment”

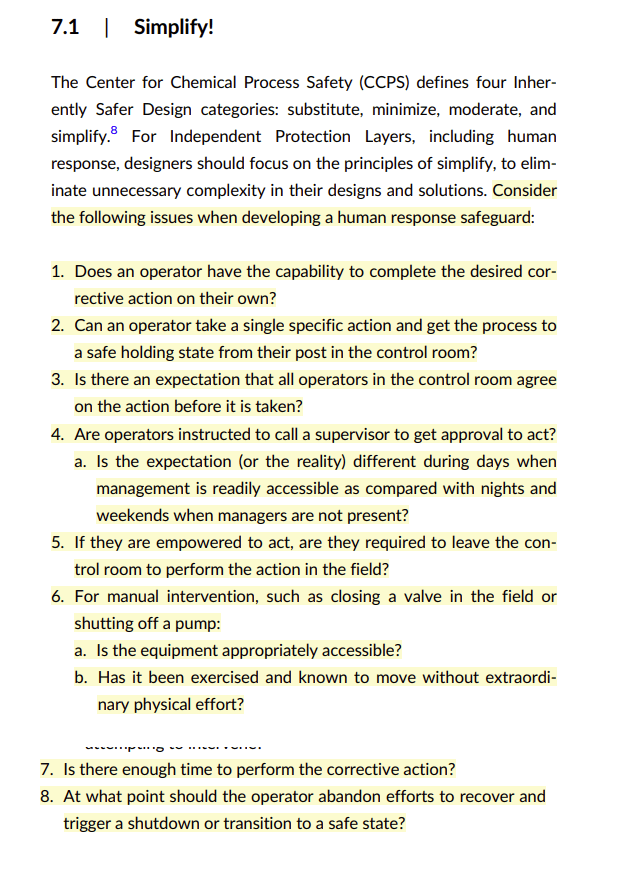

· They discuss the often robust layers of protection analysis for barriers, and argue that we should also apply this thinking to human safeguards, e.g. people “must be able to receive the information indicating an abnormal condition, decide on the best corrective action, and perform that action safely before the identified consequence occurs”

· “Are critical safety alarms different from quality or reliability alarms to prompt a more urgent response from personnel?”

· “will it be clear and unambiguous as to what specific action the operator should take?“

· “A best practice for alarm management is for all alarms to prompt an action by the operator. Information-only alarms contribute to the flood of alarms and potential confusion during upset conditions”

· “Set safety alarms outside the normal operation range so that they will clearly indicate that an abnormal situation is occurring, and operator intervention is needed”

· We should be “extremely wary about proceeding with human response as the only IPL [Independent Protection Layer] … even if all process safety time calculations and qualitative risk assessment do not eliminate it as an effective IPL”

· And “critical human response IPLs should not be buried within the operating procedure in the Safe Operating Limits (SOLs)”

Ref: Moyer, L. D., & Mize, J. F. (2025). Process Safety Progress.

Shout me a coffee (one-off or monthly recurring)

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1002/prs.70024