This study, including Amy Edmondson, studied psychological safety over time, based on a sample >10,000 US healthcare workers.

Background:

- “Today’s organizations rely on employees’ ability to learn and collaborate to succeed…[Yet] To maintain a positive image at work, people often hold back ideas, concerns, and questions, thereby negatively affecting performance”

- “Psychological safety”—a shared state of reduced interpersonal risk—describes a work environment where people believe that timely and candid sharing is possible and expected”

- “substantial research demonstrates relationships between psychological safety and learning behaviors like speaking up and sharing knowledge, the quality of one’s experience at work, and performance at the individual, group, and organizational levels”

- “Although psychological safety is most often conceptualized as an emergent property of a group … ample research indicates the importance of an individual’s belief that it is safe to take interpersonal risks”

- “studies show that psychological safety is related to initial perceptions of coworker trustworthiness … and subsequent team identification and satisfaction”

Findings:

- In this study they found that “newcomers enjoyed higher psychological safety than their more-tenured colleagues but that it was soon lost”

- “The negative effect of time on newcomers’ psychological safety makes sense given the inevitable change to their a priori understanding of what a new role entails—what Van Maanen and Schein (1979) called “reality shocks.”

- “It follows that newcomers’ initially high, then declining, psychological safety could reflect the revision of faulty a priori assumptions and inaccurate perceptions; if so, psychological safety could be especially fragile at a time when it is most needed because even a rare negative experience could dramatically skew newcomers’ belief that it is safe to take interpersonal risks given their necessarily limited experience in the organization”

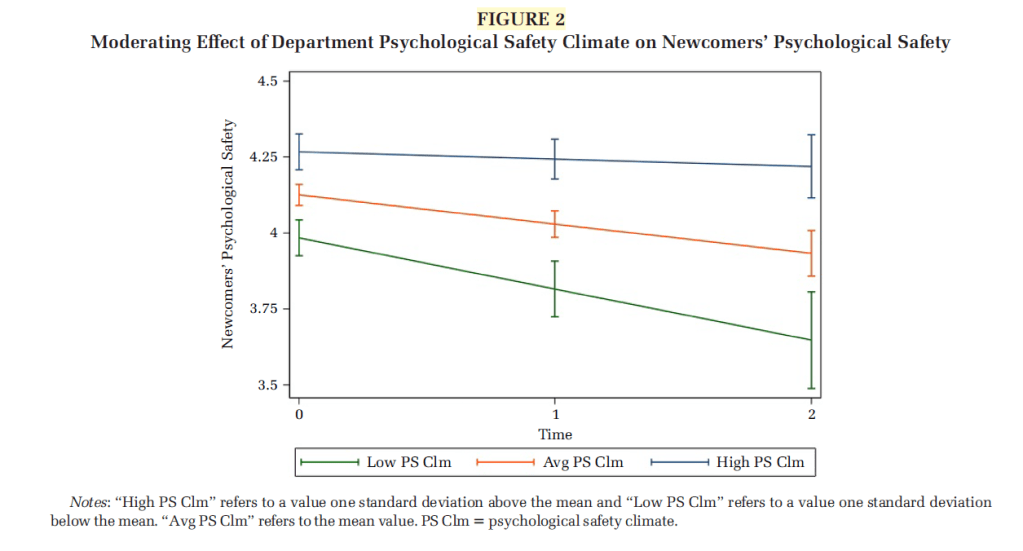

- They “also discovered that a department’s psychological safety climate influenced the trajectory of newcomers’ psychological safety. Our results revealed that high psychological safety at the department level dampened the downward trajectory of newcomers’ beliefs about whether the work environment is safe for interpersonal risk-taking”

- The findings also suggest “that individual differences could play an increasingly important role in shaping individuals’ beliefs about interpersonal risk-taking as they accrue tenure in an organization”

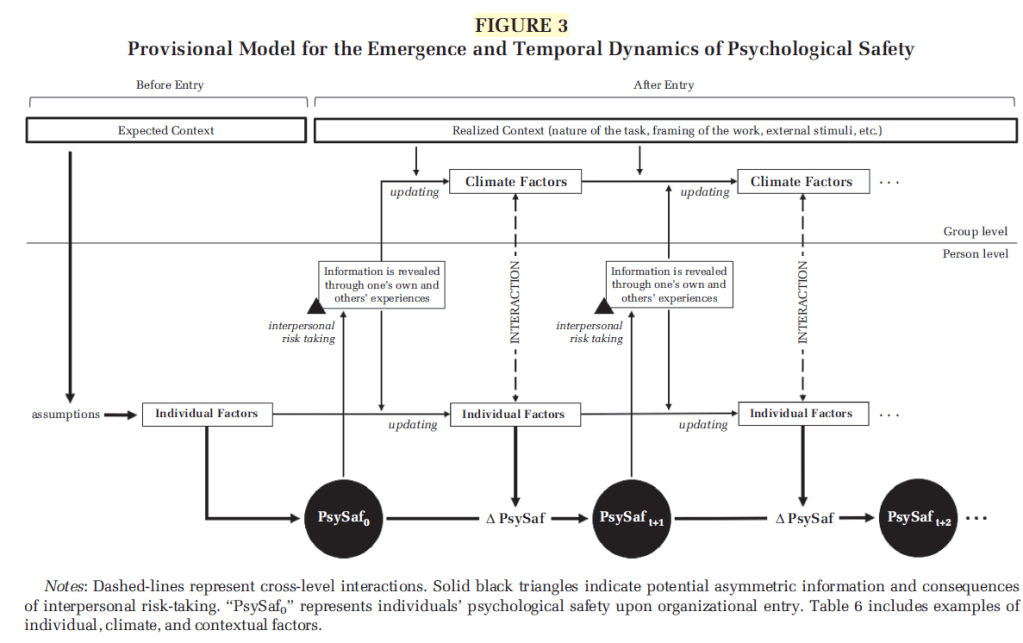

- The findings “imply that individual differences interact with group-level and contextual factors to shape and constrain the emergence and dynamics of psychological safety

- This research helps reconcile individual vs group/team level analyses of PS “pointing to a dynamic process in which individual beliefs about whether it is safe to take interpersonal risks are shaped and constrained by collective beliefs, which emerge from individual beliefs through social interactions in a group”

- “building on this insight, we propose that the influence of individual and group factors might change over time”

- The results illuminate PS as an emergent property in units larger than a team but smaller than a unit, where PS in departments “meaningfully influenced newcomers’ psychological safety”

- They “propose that change in psychological safety is jointly determined by ongoing interactions between individual and group-level factors reflecting a pattern of emergence whereby newcomers’ initial beliefs about interpersonal risk—formed quickly based on limited experience—are recalibrated over time as they engage with others in the group”

- “At the individual level, traits, perceptions, attitudes, and

- assumptions help answer the question: “How risky is this behavior for someone like me?” They pertain to competence, experience, and expectations (of oneself and others) and vary across individuals. At the group level, situational constraints, group norms, shared beliefs, and emergent states help answer the question”

- “individual, climate, and contextual factors may vary over time. Before entry, newcomers may rely on individually held assumptions to form beliefs about the risks of speaking up, sharing ideas, and asking questions in the organization. They appraise interpersonal risk based individual factors with limited appreciation of the context and little or no insight into their new group”

- “However, soon after starting their new position, they learn about their context through interactions with others and personal experiences of interpersonal risk-taking, which leads them to update their perceptions while gaining exposure to climate factors”

- “Over time, the interaction between individual and climate factors shapes psychological safety in ways that increasingly rely on climate factors and context”

- Another explanation besides a person’s initially misplaced assumptions about the interpersonal risks is a change in accountability

- E.g. “newcomers may arrive believing that others expect them to have limited knowledge, which reduces the interpersonal risk of speaking up, as they can preface interactions with the phrase “Sorry, I’m new here, but…” But, if group members’ expectations shift as time goes on—perhaps more rapidly than newcomers’ capacity to carry out the work—then newcomers may experience a new (lower) level of psychological safety”

- And “we observed the smallest difference in psychological safety, on average, between newcomers and veteran employees with more than 20 years of service—a surprising discovery that suggested it could take decades to recover the psychological safety lost in one’s first year in an organization”

- “the journey of “paradise lost and restored” could be one of shedding misconceptions, admitting fallibility, and coming to understand how to take risks in service of learning and collaboration”

- “Another powerful, if subtle, explanation for the downward trajectory of newcomers’ psychological safety involves the asymmetry between positive and negative experiences related to interpersonal risks. A positive outcome—such as an inquiry met

- with sincere interest and curiosity by a supervisor (Thompson & Klotz, 2022)—may increase (and certainly does not harm) psychological safety; positive experiences reinforce the belief that interpersonal risks can be taken, allowing future risks”

Shout me a coffee (one-off or monthly recurring)

Ref: Bransby, D. P., Kerrissey, M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2023). Paradise Lost (and Restored?): A Study of Psychological Safety over Time. Academy of Management Discoveries.