A really interesting paper exploring performance measurement and management (PMM) systems in construction.

They looked at:

· How do clients measure WHS performance in the delivery of construction projects?

· How do clients use this measurement to manage WHS performance? and

· How do performance measurement and management practices adopted by construction clients influence contractors’ WHS behaviour and outcomes?

Can’t do this justice – for a 13-pager, it is packed with data and insights.

Providing background:

· “As the initiators of construction projects, clients have the ability to influence work health and safety (WHS) in the projects they procure”

· One way this is achieved is via implementing measurement regimes to manage contractor performance

· However, “the validity of widely utilised WHS performance indicators has been questioned and the effectiveness of measurement and management regimes in influencing WHS performance across the client-contractor boundary is not well understood”

· Depending on how one defines and measures, “issues may arise if measurement focuses on the absence of particular types of incidents (e.g. those resulting in recordable injuries), without considering other factors relevant to WHS (e.g. the effectiveness with which significant risks controlled within a workplace)”

· “That is, peoples’ understanding of what constitutes safety is determined by the way that it is measured, i.e. the absence of reportable injury, rather than the presence of protection against harm”

· Frequently used lag indicators of safety are “underpinned by an assumption that WHS is a state or condition that is free from harm or risk”, and is a relatively simple measure to collect and compare against

· Such measures have “been widely criticised for being: reactive (Arezes & Miguel, 2003; Stricoff, 2000); statistically invalid (Hallowell et al., 2021); and failing to reflect the level of safety in a work system”

· Moreover, “Frequency rates based on lost time or total recordable injuries are also criticised for failing to differentiate between severe and minor incidents (Kjell´en, 2009)

· And “It is argued that grouping all injury events together in a single indicator diverts prevention efforts away from critical WHS risks that could produce serious consequences, such as fatal or life-changing injuries”

· Drawing on Hallowell et al.’s work, they note that “variation in the total recordable injury frequency is unrelated to the incidence of fatalities”

· In contrast, some organisations are adopting performance indicators which aim to measure the level of effectiveness of how WHS is being managed in the workplace

They also observe that prior research:

“have focused on the how best to measure WHS performance without paying sufficient attention to how measurement is used to manage performance”, and this gap is important because “using measurement to manage performance carelessly can produce undesirable outcomes, e.g., gaming or manipulation of data (Bevan & Hood, 2006) or create intra- or inter-organisational conflict”

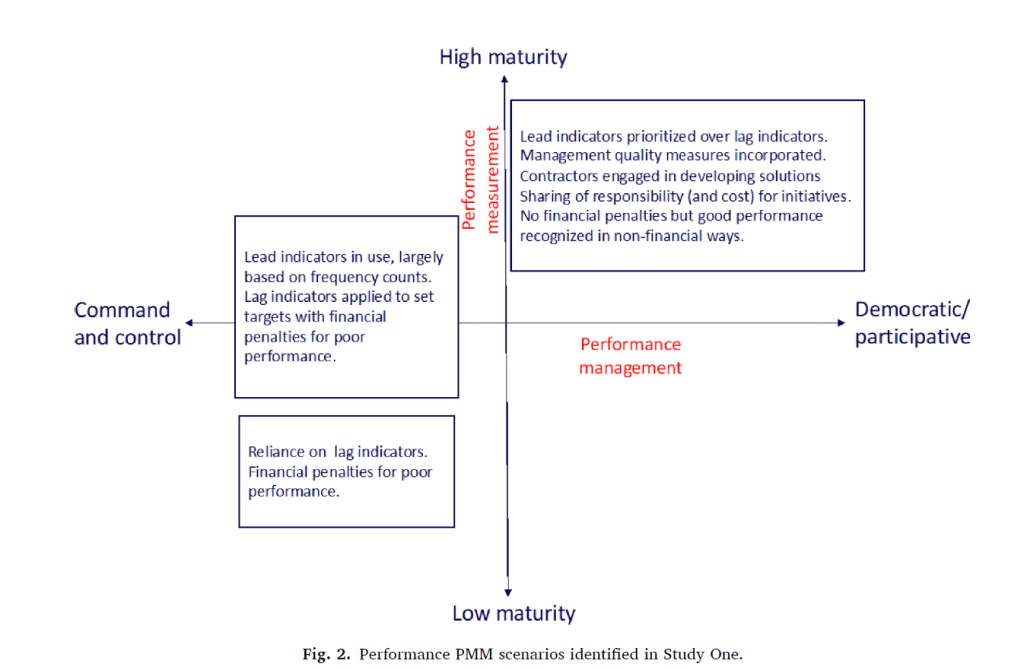

Results were divided into the below performance and measurement management regimes:

Results

Key findings were that:

· Automatic and bureaucratic PMMs produced “counterproductive behaviours, including manipulation of information, the promulgation of safety ‘clutter,’ poor quality client-contractor relationships and low levels of trust”

· In contrast, collaborative regimes led to higher levels of trust, open and honest reporting and problem-solving that was collaborative

Some informed the low maturity of their project PMM approaches – with a heavy reliance on lag indicators. Some were critical that LTIFR and the like were “not valid measures of WHS performance”.

One person said that “You can have a fatality on your job and still have an LTIFR of 0”. Another was of the opinion that LTIFR can “mask the occurrence of serious incidents that could result in a fatality or life-changing injury”.

Despite these issues, clients were seen to be hesitant to accept alternative safety performance indicators.

A command-and-control management approach was manifest in some responses as an environment where the client drives the indicators and targets. Financial penalties were seen to be linked to WHS performance in construction contracts, e.g. as one participant said: “If your LTIFR went above two you incurred a penalty…and once it was five you lost all your profit”.

Linking LTIFR with financial penalties was also said to lead to gaming the system, and hampered learning from incidents, e.g. “…whenever you hide a statistic and pretend it’s something else, you’re hiding a problem that potentially needs to be fixed”.

Nevertheless, financial penalties were seen to have little impact on the WHS behaviours of frontline personnel.

In the bureaucratic control PMMs – performance measurement is high in maturity and maintains a command-and-control style. These tended to be slightly more mature in their approach to indicators.

Whereas some believed that the move to TRIFR was more advantageous than LTIFR, in part due to being, apparently, less amenable to manipulation, others held the view that all frequency rates “are no longer considered to be reflective of WHS performance within their own organisations”.

Contractors held the view that financial penalties linked to lag indicators reduce collaboration and innovation, such that “Negative incentives don’t create a collaborative environment to resolve key issues and promote innovative approaches”. In contrast, some maintained that positive incentives would produce better outcomes.

Another thread was around more collaborative PMM approaches. For these, people still tracked lagging injury measures, but placed more focus on the leading indicators. Trust was seen to be integral here, where clients, who were still highly motivated to perform well in WHS, allowed more discretion with the contractors. Hence, clients felt less need to be overly prescriptive in these conditions.

Other findings highlighted how one client intended to maintain high WHS standards by establishing a large, 100+ page document with performance standards; principal contractors had to comply with this. This included a health and safety performance index, comprised of >50 individual performance metrics. Contractors were expected to submit monthly reports for review by the client, and the safety index was used to score each principal contractor.

Contractors informed that a more collaborative approach would involve less focus on statistics, and more client involvement in conversations.

One client representative “acknowledged that a pre- occupation with audits, which were seen to mostly focus on less significant WHS issues, was potentially diverting attention and resources away from more significant WHS issues”.

Contractors viewed these overly prescriptive or onerous monitoring systems as “ an administrative burden that did not necessarily contribute to improved WHS performance”. These were seen as box ticking exercises.

Discussion

Overall, they argue that:

· “WHS performance measurement approaches adopted by clients in the construction industry are often low in maturity”

· Some projects placed “a heavy emphasis on lag indicators indicating that some construction clients view WHS solely as a state in which incidents or injuries are absent”

· Participants recognised that lag indicators, and particularly LTIFR, “are under-reported and manipulated by contractors who seek to cover-up incidents and injuries in order to avoid financial penalties”

· TRIFR is also seen to be problematic because “of concerns that grouping all injury events together in a single indicator can conceal severe injuries and divert prevention efforts away from activities that pose a critical WHS risk”

· Likewise, over-reliance on TRIFR can provide a false sense of safety, as “the absence of incidents or injuries does not mean that a workplace is safe due to the lack of statistical validity of the TRIFR as a measure at project level”

· A strong preoccupation with client audits was also seen as an administrative burden that focused on relatively minor issues, and “created an illusion of control”

· Interestingly, they observed that even when lead indicators are implemented, “these indicators typically measure the frequency of contractor WHS management activities, rather than directly measuring WHS conditions in the workplace”

· Hence, the measures are indirect measures of WHS performance and not direct

· Some maintained that “relying on simple frequency counts of activities in a given period is unhelpful” and that “lead indicators that measure the frequency of management actions can motivate behaviour that produces no material WHS benefits and can even increase risk exposure”

· Finally, the findings suggest that “WHS measurement and management approaches adopted by construction clients in relation to WHS performance interact to produce particular outcomes. Sometimes these outcomes could be described as unintended consequences”

Ref: Lingard, H., & Pirzadeh, P. (2025). Workplace health and safety performance at the client-contractor interface: Measurement, management and behaviour. Safety Science, 184, 106753.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2024.106753

My site with more reviews: https://safety177496371.wordpress.com

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/workplace-health-safety-performance-client-contractor-ben-hutchinson-nk6mc

One thought on “Workplace health and safety performance at the client-contractor interface: Measurement, management and behaviour”