This brief conference study explored gaps between work-as-imagined (WAI) versus work-as-done in the field during real work tasks.

Six workers at a petrochemical facility wore helmet mounted cameras and recorded undertaking filling operations. The video was then used to compare work practices against written process and coded using the WAI / WAD framework shown below:

As shown above, the key elements are:

- Skip: was the task step skipped or performed as intended

- Order: was the step completed in the order specified by the procedure

- Action: Was the step performed as prescribed by the procedure

Providing context, the authors briefly cover perspectives of work and procedural “deviation” from a Safety-I and Safety-II perspective. Of main note is that this study explored “deviation” more as process variability.

That is, “organizations need to recognize that performance variability is inevitable and necessary for a system to remain functional”. Variability is a normal and sometimes essential facet of maintaining reliable and safe performance but can also introduce unintended failure modes and the like.

RESULTS

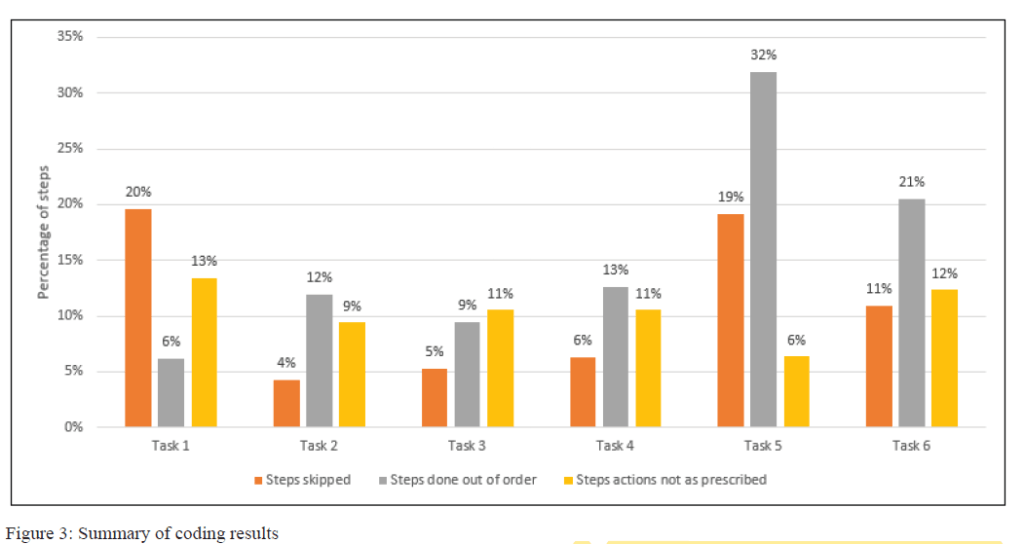

524 steps were analysed from the six filling tasks.

Key findings were:

- Most (66%) of the steps were carried out as prescribed by the procedure

- In about a third (34%) of the steps, WAD didn’t equal WAI

- Most differences between WAI and WAD were due to steps being conducted out of the prescribed or described order (11% on average)

- This was followed by steps not being conducted as prescribed (10%)

Findings are shown below:

They argue that differences between WAI and WAD could broadly be classified as being due to:

1. Safety-critical: Steps inconsistent between WAI/WAD because they were completely skipped or partially completed or completed differently or out of order and these steps were considered to be critical to safe operations.

Most steps classified as safety-critical (the types that, theoretically, should be most consistent with WAI), were also those steps that most workers skipped. Two of the workers overlooked similar types of safety-critical steps.

The authors note that organisations should invest time and resources to learning more about safety critical steps, how workers complete them, and find ways to improve adherence [* not just via the workers but also the design of the work, plant, conditions etc.]

2. Routine: These steps were coded inconsistent between WAI/WAD because a particular step was completely skipped, partially completed or completed differently. These inconsistencies weren’t considered any threat to the safety of operations.

These modifications occurred largely due to norms of that particular facility or workgroups.

Numerous factors could help explain these norms, including misperceptions or misunderstandings of the process or a lack of clarity on the importance of steps. They cite a study indicating that experienced workers create inaccurate mental models of the perceived importance of some steps in a task.

More interesting from an organisational and human factors perspective is whether the procedure is inadequate or “does not entirely represent how the task is done” (p1808).

3. Efficiency: Steps coded here where WAI didn’t equal WAD resulted from steps being completed as prescribed but not in the correct order.

These steps were generally done to be more efficient. They argue that while “Safety I principles would consider this a violation, under the Safety II philosophy, these adaptations at work are inevitable” (p1808).

Irrespective of the perspective taken, the inconsistencies between WAI and WAD provide intel for learning about work.

Moreover, these activities may permit more depth to learning, where inconsistencies aren’t purely seen as worker-related issues (complacency or lack of training) but considered as joint systems of analysis where the context and environment are also seen as strong contributing factors (poor work design, support, resources, trade-offs etc.).

In my view – I think this study and similar ones highlight just how much unity and consistency there is between different safety camps (S-II/new view vs behavioural and BBS and the like). We’re all interested in work and context but have different ways to express it.

Authors: Ashraf, A. M., Peres, S. C., & Sasangohar, F. (2022, September). In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting (Vol. 66, No. 1, pp. 1805-1808). Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1177/1071181322661310

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/investigating-new-classification-describe-differences-ben-hutchinson

2 thoughts on “Investigating a new classification to describe the differences between Work-As-Imagined and Work-As-Done”