Another interesting study which explored some of the limits of psychological safety (PS).

This study looked at the role of PS, felt accountability and other factors on New York school performance over 3 years, based on surveys of 170k teachers from 545 schools.

Providing background:

· Prior PS research has highlighted how it likely best works as a team construction, but evidence is less certain about when there is less interdependencies between individuals

· Even less research has evaluated PS at the organisational level, such at the level of a school as this study evaluates

· Some contexts don’t revolve tightly around teamwork like in hospitals, for instance in schools “the focal workers, teachers, do not perform the bulk of their daily work in teams; rather, teachers generally work behind classroom doors and carry out their work independently rather than interdependently”

· Despite the various benefits of higher PS that has been demonstrated, some exceptions exist. Some research has shown that higher PS may result in higher team unethical behaviour, in other work PS may have an indirect effect on team-level outcomes rather than direct effects

· Other works highlights that PS may serve as a mediator between team structure and team learning

· Another relevant concept is felt accountability, said to operate alongside PS. Felt accountability is “an implicit or explicit expectation that one’s decisions or actions will be subject to evaluation by some salient audience(s) (including oneself)”

· Felt accountability may “help explain the conditions under which psychological safety has a positive versus negative impact on various outcomes (Deng et al., 2019). In other words, psychological safety may be more complicated than originally conceived, in that its effects are not always positive”

· Other research suggests that PS may have positive or negative effects on performance depending on which underlying mechanisms are at play. For instance, “psychological safety may reduce group members’ fear of failure that can naturally arise when faced with learning tasks, and thus positively affect a group’s risking-taking behaviors” whereas conversely “psychological safety may reduce worker motivation such that group members exert less effort, yielding a negative effect on a group’s risk-taking behaviors”

Overall, they evaluate the following questions:

· How does psychological safety impact organizational performance over time?

· Regarding felt accountability, How does felt accountability impact organizational performance over time?

· How do psychological safety and felt accountability together impact organizational performance over time?

· What is the best combination of psychological safety and felt accountability for organizational performance over time?

This paper is pretty long and dense, so I can only scratch the surface.

Results

Key findings:

· Multi-level analyses showed that “psychological safety is not on its own, nor necessarily, “helpful” with regards to organizational performance over time”

· Rather, “the best conditions for fostering organizational performance occurred when psychological safety was relatively low and felt accountability was relatively high” (emphasis added)

· When PS is considered on its own “all else held constant, psychological safety had a negative effect on performance over time” (emphasis added) whereas in contrast “we found the opposite to be the case for organization-level felt accountability: it had a positive impact on schools’ likelihood of reaching their performance targets over time, all else held constant”

· Best performance over time wasn’t when both PS and felt accountability were high or even balanced, but the best performing schools were those “with relatively low psychological safety and relatively high felt accountability”

These perhaps counter-intuitive findings suggest that “psychological safety’s effect on performance is more nuanced than found in prior research, with higher psychological safety not simply or directly enabling better performance—and perhaps even hindering performance—when considered on its own”.

Indeed, while one may expect schools with higher employee perceived PS to have a better chance of achieving annual education targets, they found the opposite. Schools with higher perceived PS performed worse.

In contrast, schools with higher felt accountability had a higher likelihood of achieving their annual targets.

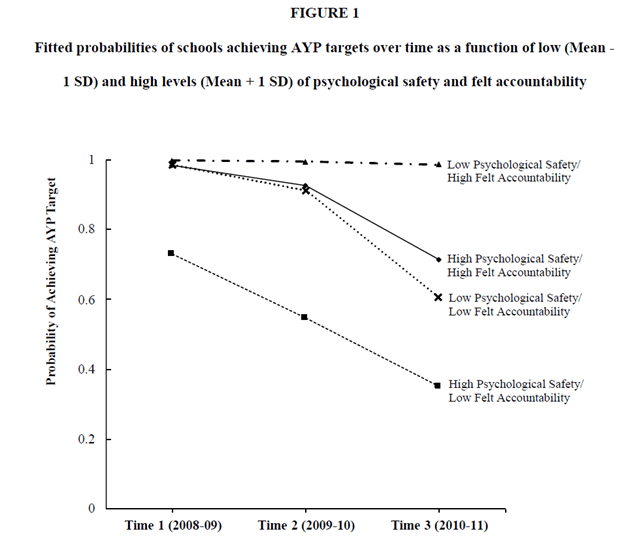

Further they note that based on their three-way interaction statistical model, the likelihood of schools achieving their targets “suggests the impact of psychological safety on schools’ likelihood of achieving their AYP target varied by the amount of felt accountability present in the school and over time”.

Schools that started with high PS and low felt accountability performed worse over time – performing worse at the start and then declining more rapidly than other combinations. Schools with low PS and high felt accountability started off well and declined only very slightly (such that they nearly achieved 100% of targets over time).

Thus, for the “best combination”, they note that “the combination of relatively low psychological safety with relatively high felt accountability was the undisputed, yet unexpected, winner”.

For explanations, they have a few speculations and evidence-based predictions. Based on a previous study which found that PS was a double edged sword, they say that “people tend to exert less effort when they do not feel accountable”, speculating that schools with higher perceived PS were coupled with little felt accountability.

Moreover, without appropriate controls and management around psychological safety and voice behaviour, a type of “complaining zone or spiral when workers feel frustrated about their jobs” but have little perceived accountability or power to change things.

In contrast, the authors argue that “Teachers who felt accountable, particularly in environments with relatively low psychological safety, may simply have been putting their heads down and focusing on the task at hand—improving instruction, which then yielded positive benefits in terms of student achievement”.

They provide other possible explanations for their findings which I’ve skipped. However, importantly, simply creating free or open dialogue with the intention of higher PS may not produce expected goals. That is, “Simply opening up this kind of space to create a high psychological safety workplace might make individuals feel too “comfortable”.

In sum, managers need to be thoughtful about how “psychological safety might also have a dark side if it is not well managed”. Managers should thoughtfully open up the inquiry space for open dialogue but also recognise “possible tripwires that could emerge”.

Here, managers could offer “scaffolding to support that inquiry space through vehicles such as thoughtful agenda-setting, creating collective incentives, and/or designing meetings around problems of practice identified by those closest to the work itself”.

Authors: Higgins, M. C., Dobrow, S. R., Weiner, J. M., & Liu, H. (2022). Academy of Management Discoveries, 8(1), 77-102.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2018.0242

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/when-psychological-safety-helpful-organizations-study-ben-hutchinson-edsic

2 thoughts on “When is Psychological Safety Helpful in Organizations? A Longitudinal Study”