Another post on SIFs, this time the High Energy Control Assessments (HECA) from Oguz Erkal & Hallowell.

Link to article below, plus to a HECA guide, and to the SIF compendium.

Extracts:

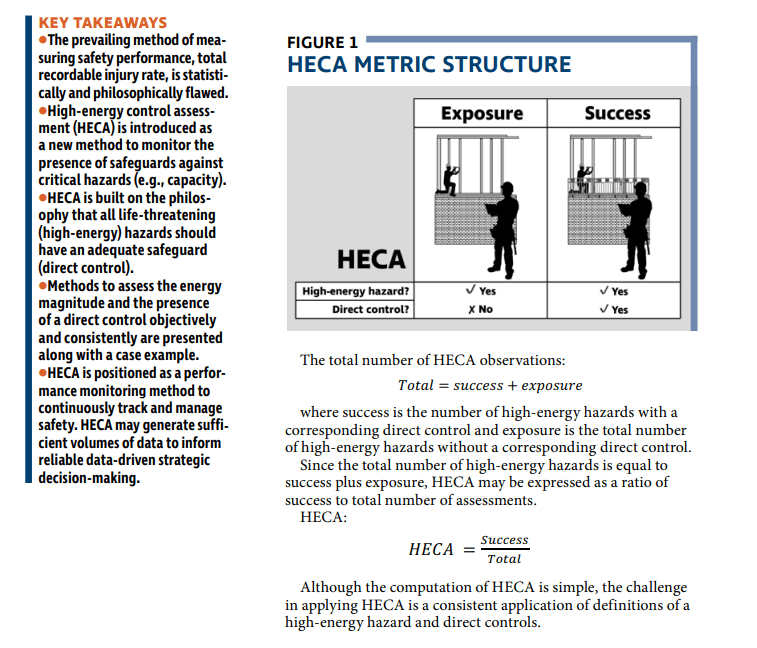

· HECA is “the percentage of high-energy hazards with a corresponding direct control”

· HECA is binary because “every condition observation is modeled only as success (the high-energy hazard has a corresponding direct control) or exposure (the high-energy hazard does not have a corresponding direct control)”

· HECA is simply calculated as – total number of HECA observations: Total = success + exposure, with success being the # of high energy hazards with a direct control, and exposure the total # of high energy hazards

· HECA can then be expressed as a ratio – HECA = Success / Total

· High energy is based on research showing that injury severity is directly related to the magnitude of physical energy with a hazard

· “Hallowell et al. (2017) found that hazards with fewer than 500 joules of energy are most likely to cause a first aid injury; hazards with between 500 and 1,500 joules of energy are most likely to cause a medical case injury; and hazards with more than 1,500 joules of physical energy are most likely to cause a serious injury or fatality”

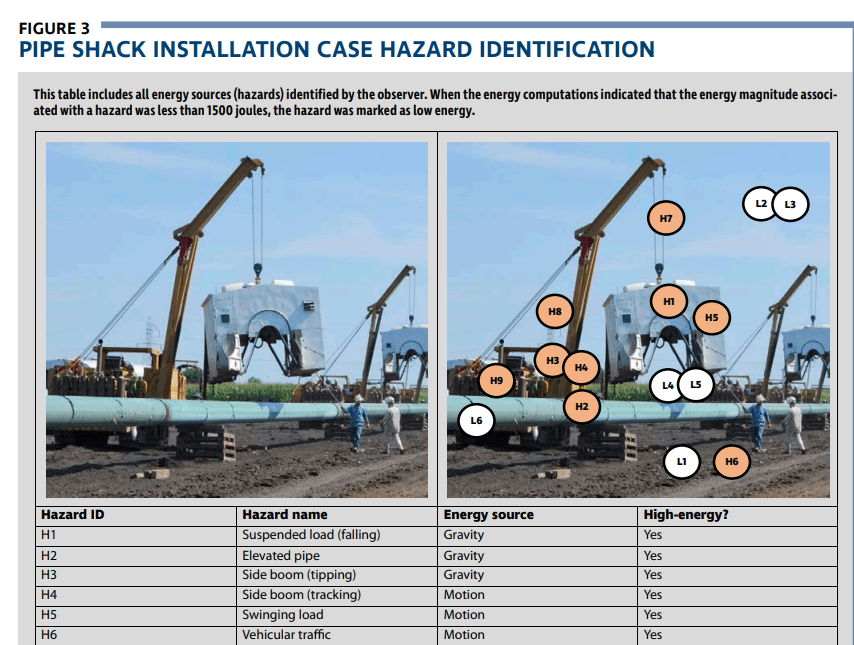

· Thus, “high energy” is hazards with 1,500 J of energy, as these interactions are most likely to be a SIF

· “Put simply, high-energy hazards are the life-threatening hazards”

· They suggest focusing on the “most likely outcome associated with a hazard” rather than the worst case

· They discuss the use of 13 energy icons for undertaking the field assessments – these cover ~85% “of all high-energy hazards documented in the literature as primary causes of SIFs”

· These are designed for practical analysis, but don’t cover every high-energy hazard

· Next they discuss direct controls, which have three criteria:

1) Targets the high-energy hazard

2) Effectively mitigates the high-energy hazard when installed, verified and used properly (e.g. must either eliminate the energy or reduce energy exposure to <1,500 J)

3) “Effective even if there is unintentional human error during the work (unrelated to the installation of the control”

· On the 3rd point, they note “Controls are not considered adequate to protect against life-threatening hazards if they require workers to be perfect when using them. Given enough time, the probability that a worker will make an unintentional error is 100%”

· And these controls “must be functional even when someone makes a mistake during work”

HECA as a measure:

- “HECA Is Neither Leading nor Lagging; It Is a Method of Monitoring”

- It’s not leading because it doesn’t measure safety activity, and although its an output metric it “represents a consequence of the safety system, but precedes the occurrence of a serious safety incident”

- It rather sits “in the middle from a timeline perspective as a monitoring variable that may moderate or explain the relationship between leading and lagging variables”

- They provide an example of how to apply it, with one suggestion for the observation: 1) list the high energy hazards, 2) assess and describe whether a direct control was observed, 3) for those without a direct control, what was missing?

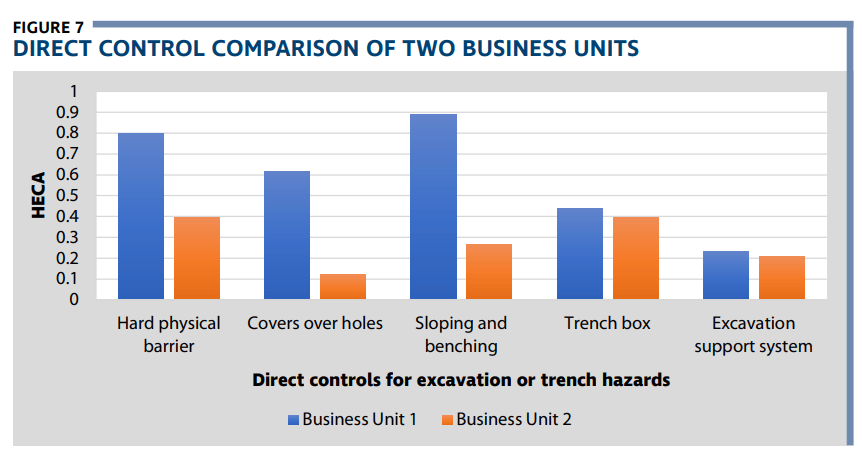

- They say HECA can be reduced to a single number, it “could be used to summarize historical safety performance as a metric that tracks the percentage of high-energy hazards that have corresponding direct controls”

- But, importantly, HECA should be used for learning and improvement over measurement and comparison

- Metrics used for comparisons have “the potential to directly or indirectly be incentivized” and HECA is no exception, and “When incentivized, any metric can encourage poor behavior such as underreporting, misreporting .. and other forms of data manipulation”

Report 1: https://www.safetyfunction.com/_files/ugd/3b3562_a424fd76598143e78b4580176e674ac4.pdf

SIF compendium: https://safety177496371.wordpress.com/2025/04/15/compendium-sifs-major-hazards-fatal-traumatic-hazards-risks/