A brief article from Hollnagel on the ‘arbitrariness’ of accident analyses.

Relying on a lot of direct quotes.

First it’s argued that one of the many myths within safety is that accident analysis / investigation “is a rational search for (root) causes”.

By this logic, the purpose of an investigation is to found out what happened so as to prevent its reoccurrence. We assume the process of finding out how something happened is a rational process of pursuing causes.

To Be Safe

We typically rely on ‘accident models’ to make sense of adverse events. This isn’t necessarily the specific tool we use, but model in the sense of a mental model or belief system of accident causation.

“All accident models share the unspoken assumption that outcomes can be understood

in terms of cause-effect relations”. Hollnagel refers to this as the causality credo – which is itself a safety myth. The causality credo is:

· An accident is an effect and therefore has a preceding cause. There is “an evenness between causes and effects, which means that an accident happens because something has failed or malfunctioned”

· Causes can be found if enough evidence is collected, and once identified, can be eliminate or mitigated

· “Since all accidents have causes, and since all causes can be found, it follows that all accidents can be prevented”

The latter is said to be a seductive allure within zero harm approaches.

Using these logics, safety management seeks to ensure nothing goes wrong, and “We can therefore be safe if we can ensure that nothing goes wrong”.

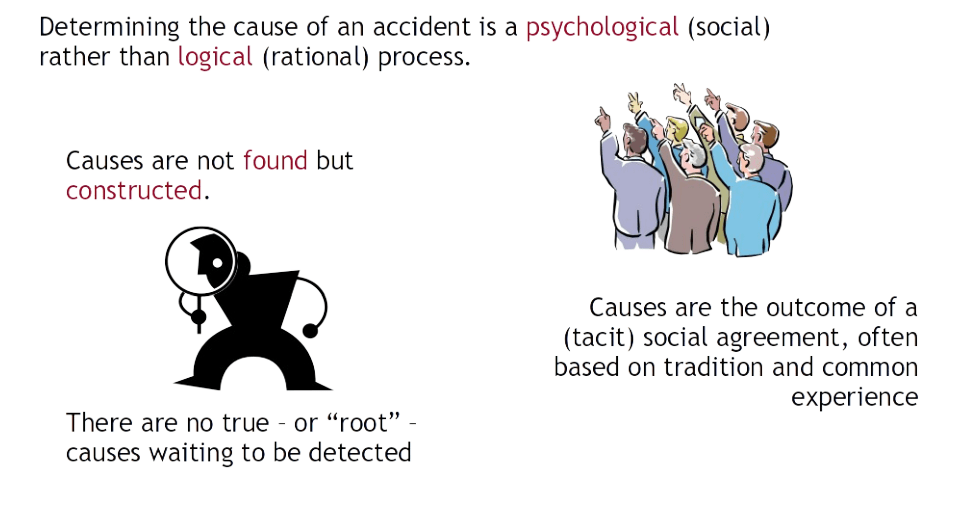

We believe that investigations are logical and rational processes of finding causes ‘out there’ in the world. Yet, they’re influenced heavily by the underlying cultures, mental models (accident models), tools, time and political pressures and more.

Investigations are also shaped by the What-You-Look-For-Is-What-You-Find (WYLFIWYF) principle. It is “a consequence of the WYLFIWYF principle that the assumptions about the nature of accidents, the causality credo in particular, constrain the analysis”.

That is, if your accident model is the belief that most accidents are due to human error or agency, then you’ll inevitably find (** construct **) human agency in investigation causality.

To Feel Safe

Accidents are said to be “unexpected, even when they are imaginable”.

Because we’re taken by surprise, “they are psychologically unpleasant”. Since humans have a basic need to feel safe, we need to “restore our feeling of safety” in response to incidents.

Hence, ‘finding’ causes has practical value, “because knowledge of the cause is seen as necessary to prevent that the accident is repeated”. But it also has psychological value for relieving the anxiety that results from the unknown and lack of perceived control.

Since a cause is “the identification, after the fact, of a limited set of aspects of the situation that are seen as the necessary and sufficient conditions for the effect(s) to have occurred”, we can reduce anxiety and feel safe by thinking of an “acceptable explanation for the unexpected”.

To Really Be Safe

Here it’s argued that safety has conventionally been defined as “a condition where the number of unwanted outcomes (accidents / incidents / near misses) is as low as possible (Safety-I)”.

But, this “deceptively simple definition is however problematic because it defines safety by its opposite, by what happens when it is missing”.

That is, the conventional view of what safety ‘is’ defines the presence of safety by its absence, and means that safety is therefore measured indirectly, “not as a quality in itself, but by the consequences of its absence”.

[*** Others have called this focus and measurement on the absence as ‘unsafety’, e.g. measuring the absence of safety capacities]

While it’s understandable why we’d focus on what goes wrong, when something goes wrong it can’t also be going right at the same time. And “We could therefore also look at how things go right, and define safety as a condition where as much as possible goes right (Safety-II)”.

From the S-II perspective, safety is about ensuring everyday work succeeds sufficiently. This also includes learning proactively from daily work in conjunction with what goes wrong.

[** My view: I think it’s misleading when some practitioners suggest that ‘traditional’ approaches doesn’t have a proactive focus, since it does; though FYI Hollnagel isn’t actually arguing this.]

Learning about how to create safe and effective work “requires an understanding of the nature of successful work, of how the work environment develops and changes, and of how functions may depend on and affect each other”.

This involves searching for patterns and interrelations across events rather than solely on that individual event.

Finally, it’s “more important really to be safe making sure that everything works as it should, than to feel safe by clinging to socially acceptable causes”.

Shout me a coffee (one-off or monthly recurring)

Ref: Hollnagel, E. (2015). ErikHollnagel.com

Study link: https://erikhollnagel.com/onewebmedia/Arbitrariness_of_accident_analysis.pdf

Safe AF LinkedIn group: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/14717868/