This paper explores Rio Tinto’s evolving approach and adaptation of their Critical Control Framework.

They integrated the most useful parts from ICMM, Energy Institute, & CCPS.

The paper was motivated by an ‘uplift program’ at Rio, involving a complete review and alignment of their approach to controls and critical control management, including definitions and improved clarity on applied use.

Note: I’ve skipped a lot. It’s an interesting paper and recommend you track down the full-text if you can.

For some context, they note the value of better defining the bow tie top event. Top events are useful for shifting focus to proactivity and away from reactivity, since it’s the point where control of the process/scenario is lost. An example was reclassifying a top event as ‘unplanned slope instability’ rather than the actual loss of stability/collapse, since this captures opportunities to address instability before collapse.

Control / Critical Control Definitions

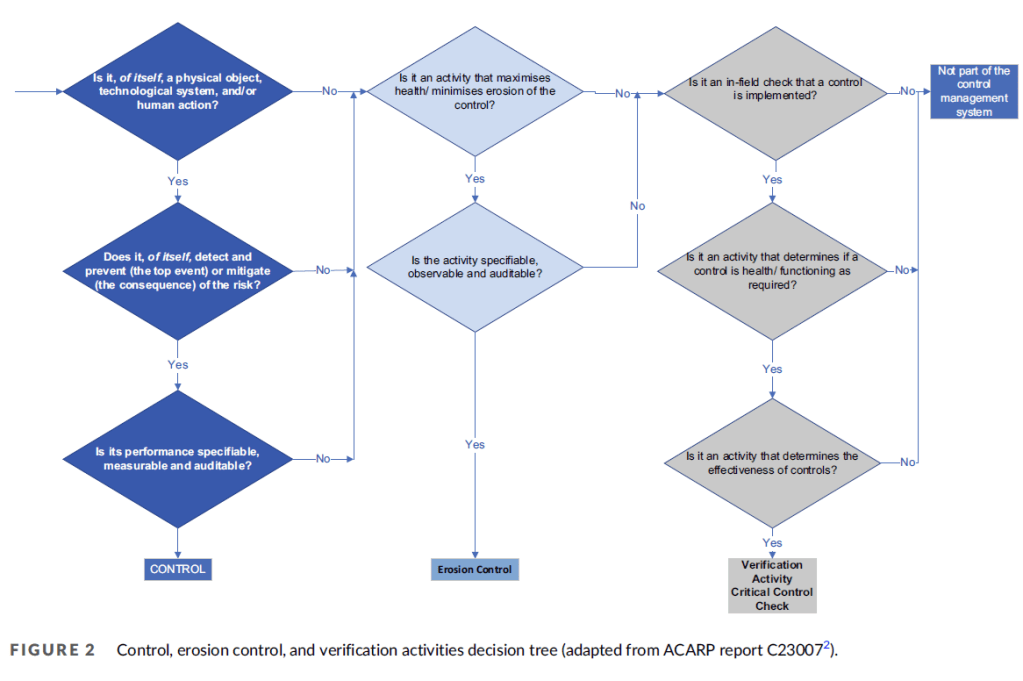

They talk about their definitions. A previous definition of control was a “measure that prevents or mitigates a threat, or maximizes positive outcomes to achieve objectives”. The control’s performance must be specifiable, measurable and verifiable/auditable.

They revised this definition to:

“Controls are any measure that prevents or mitigates a risk to achieve its objectives”.

In the bow tie context, controls include preventative or mitigative measures to manage identified hazards. This includes physical objects, technological systems, and/or human action.

They note that each control “must have the ability of itself to detect and prevent, or mitigate the risks associated with a hazardous event”.

Of itself meaning that the control can directly prevent or mitigate the unwanted event sequence. In order to be reliable and effective, and hence achieve its specifiable performance (as outlined earlier), there must be “clear metrics in place to evaluate its effectiveness regularly”.

Next they cover things that are not controls. Activities that help maintain the health of the control, or prevent the erosion of the control effectiveness aren’t of themselves control, but they’re erosion controls. They give examples like maintenance of safety instrumented functions, critical procedure training and design reviews.

Such activities help maintain the dependability of the control to achieve its function but do not directly prevent or mitigate the unwanted event.

Moreover, “Plans are typically not considered a control because, of itself, they do not prevent or mitigate the unwanted event”. As such, consider what specific activities within the plan achieve the definition of a control.

Further, activities that are in-field checks that the control is implemented and functioning aren’t controls, either, but, obviously, verification activities.

With application of these tightened definitions they observed “many disciplines, particularly in the major hazard of tailings, slopes, and underground, found that many previously group-defined controls were identified as erosion controls”.

Hence, they were able to reduce the number of controls, and critical controls, down to the important few. And shift support activities to erosion controls.

Critical Controls

For CC, Rio had been exclusively using the ICMM’s definition. Interestingly they note that because they’re not just mining, but have extensive processing facilities and mineral businesses, they felt the need to incorporate best practices from other domains in process safety and oil & gas.

The prior definition of a CC was:

“A critical control is a control that is relied upon to enable an opportunity, or prevent or mitigate a threat, such that the absence or failure of the critical control would substantially impact the risk, despite the existence of other controls”

They revised the CC definition to:

“Critical controls can either independently stop the cause initiation to the top event or reduce the magn-tude of the consequence, or the absence or failure of this control would significantly increase the risk of the unwanted event [backed up by data/evidence]”

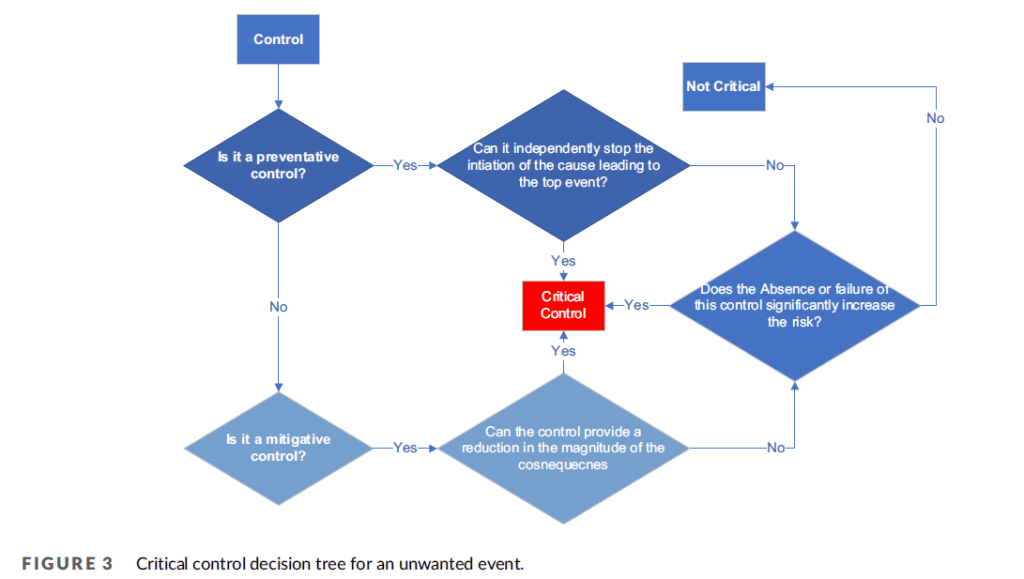

To be critical, it must meet one of the specific criteria:

1. If it’s preventative, then must independently stop the cause initiation

2. If it’s mitigative, must independently provide a reduction in the consequence magnitude of a fatality or injury

3. If independence can’t be determined, the absence or failure of this control would significantly increase the risk [backed by some data or evidence]

They note that a key change in definition was removing the positive opportunities in the prior definition, and focusing purely on the threat management. They also note that the new focus on independence was taken from LOPA (Layers of Protection Analysis). [** Independence is also common within oil & gas barrier approaches]

Curiously, they state that the ICMM question ‘‘Does the absence of failure of the control significantly increase the risk’ was clarified to have to include evidence and not just based on subjective decision-making. Evidence can be internal and external incident and near-miss info, and this is used to “determine controls, that may not meet the requirement of independence, but that data would show that their failure has contributed significantly to incidents”.

[** I write curiously since, while I think I understand the intent, some caution is also needed when trying to blunt people’s heuristics and instead rely on codified data since not everything important can be clearly and ‘objectively’ quantified. Paraphrasing Charles Perrow, sometimes we need more possibilistic thinking than probabilistic thinking.]

They also revised the control definition incorporating the Detect, Decide and Act framework (abbreviated sometimes as DDA, or IDDA, or IDDR (respond instead of act)). This is also common in oil & gas barrier approaches (and likely in process industry applications).

They again note how these revisions helped fine tune the selection of the most critical controls, and build a body of support activities (erosion controls) that support the control reliability, but are of themselves not controls.

The paper then discusses how they implemented these approaches and the barriers they faced. I’ve skipped these sections.

Ref: Anato, L., & Morar, C. Enhancing critical control management using bowties for high consequence risks at Rio Tinto. Process Safety Progress.

Shout me a coffee (one-off or monthly recurring)

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1002/prs.70008

Safe AS LinkedIn group: https://www.linkedin.com/groups/14717868/

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/enhancing-critical-control-management-using-bowties-high-hutchinson-yjvoc