Here’s a mini-compendium of research surrounding leadership, safety leadership and followership.

NOT systematic – there’s way too much to cover in this space. Focus is on the links between leadership attributes / interventions on indices of performance.

The other focus is on studies I’ve either summarised or could locate a full-text link for.

** For some reason, the formatting and images have broken or become janky. You may find the LinkedIn version easier (will post it at the end of this article) **

Feel free to shout a coffee if you’d like to support the growth of my site:

Critical Works / Discussions

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2023.101770

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2024.115036

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.104568

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.104534

Leadership/CEO/Boards & Accidents

SafetyInsights.org

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgDoes CEO overconfidence affect workplace safety?

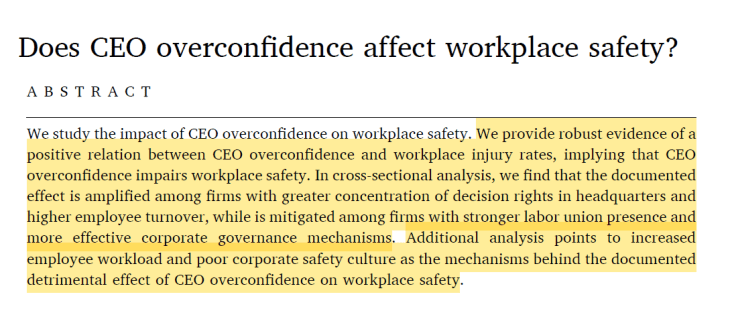

Does CEO overconfidence affect workplace safety?

This studied the relationship between CEO overconfidence and workplace safety.

Data was drawn from OSHA and firm financial performance and CEO compensation.

For background:

- “Overconfidence reflects the tendency of individuals to think they are better than they really are on relevant characteristics, such as ability, judgment, or prospects for successful outcomes (Hirshleifer et al., 2012)”

- “Individuals exhibit higher levels of overconfidence when they are (or perceive to be) in control and are committed to or emotionally invested in the outcome (Weinstein, 1980)—settings that characterize CEOs as the key corporate decision makers, implying that overconfidence bias is reinforced among CEOs”

- “Consistent with this, CEO overconfidence has been shown to influence a wide range of corporate decisions including investments, capital structure, and innovations”

- “prior literature suggests that CEOs influence corporate policies by “setting the tone at the top”, which results in their personality traits becoming imprinted on the firm”

- “Consistent with this notion, a growing stream of research highlights that CEOs play a critical role in developing a climate of organizational safety by role modelling their workplace safety-related values and behaviours to lower-level managers and supervisors”

- “the above insights cast CEO overconfidence as a potentially important antecedent of a firm’s workplace safety policies”

- “overconfident CEOs are likely to underestimate the probability of workplace accidents in their firms and, consequently, expected costs related to such incidents”

- “When making decisions regarding workplace safety policies, companies must weigh investments in costly safety measures (such as investing in equipment with better safety features, automating dangerous tasks, and training of employees) versus the costs related to safety incidents (Bradley et al., 2022)”

- “Accordingly, firms led by overconfident CEOs may be less prone to undertake activities that reduce the risk of on-the-job injury and, thus, are more likely to have poor corporate safety culture”

- “prior research documents that overconfident CEOs tend to issue overoptimistic earnings forecasts (Hribar and Yang, 2016) and that managers may be willing to increase employees’ workload to meet overoptimistic earnings targets to the detriment of employees’ safety”

- “overconfident managers tend to systematically underestimate the probability of negative events … It follows that an overconfident CEO may perceive a lower likelihood of a firm becoming financially constrained in the future, which in turn could facilitate a firm’s investments in workplace safety”

Key findings were:

- “positive relation between CEO overconfidence and workplace injury rates, implying that CEO

- overconfidence impairs workplace safety”

- “In cross-sectional analysis, we find that the documented effect is amplified among firms with greater concentration of decision rights in headquarters and higher employee turnover, while is mitigated among firms with stronger labor union presence and more effective corporate governance mechanisms”

- “increased employee workload and poor corporate safety culture as the mechanisms behind the documented detrimental effect of CEO overconfidence on workplace safety … consistent with the notion that overconfident CEOs tend to allocate more workload to employees”

- Next they compare CEO overconfidence on corporate safety culture scores, saying “firms led by overconfident CEOs tend to have a poorer corporate safety culture”

- “Our study extends the literature on both CEO overconfidence and workplace safety by casting CEO overconfidence as an important antecedent of a firm’s workplace safety policies”

- “corporate board members should be mindful of the adverse effect of CEO overconfidence on workplace safety when assessing the cost-benefit balance of employing overconfident CEOs”

Ref: Chen, Y., Ofosu, E., Veeraraghavan, M., & Zolotoy, L. (2023). Does CEO overconfidence affect workplace safety?. Journal of Corporate Finance, 82, 102430.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2023.102430

My site with more reviews: https://safety177496371.wordpress.com

SafetyInsights.org

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgSafety First – Overconfident CEOs and Reduced Workplace Accidents

This was really interesting. It studied CEO investment style on workplace safety.

Two styles were included: underconfident and overconfident CEOS. Underconfident CEOs are those that are less certain about future company value or performance and thus underinvest in order to maximise short-term value.

Underinvestment has been shown to contribute to workplace accidents. Underinvestment can involve too little investment in CAPEX which can result in old machinery, poor maintenance, and lack of safety features.

Conversely, overconfident CEOs – those CEOs that overinvest in CAPEX and R&D to maximise future performance, since they’re confident the investment will pay off, are hypothesised to inadvertently have a positive impact on workplace safety. This is because while trying to maximise future earnings, the newer equipment introduces new safety protocols and features.

Note that an interesting feature of this study isn’t about CEOs that prioritise safety or not but rather how CEOs inadvertently create safer environments by investing to enhance the financial performance of the company.

There’s way too much to cover in this paper both for the methodology and findings. But data was based on all CEO compensation data from 1992 – 2015 for that region and a host of other data.

Results

As expected, overconfidence (again, CEOs that overinvest in CAPEX & R&D, which creates asset growth and PP&E growth) is associated negatively and statistically significantly with accidents after controlling for a host of factors (negative association as in, as overconfidence investment goes up, accidents go down).

This effect was also economically significant. Quoting the paper, “a one standard deviation increase in CEO confidence is associated with a 2.1 percentage point reduction in the number of accidents per year” (p3). Further, they found that “overconfident CEOs [were] associated with a 14 percentage point reduction in the number of accidents for firms with internal capital constraints, and a 19 percentage point reduction for those with borrowing constraints” (p4).

In all, overconfident CEOs experience around 2.4% fewer accidents compared to underconfident CEOs and 1.3% fewer accidents per employee.

For other findings:

· R&D intensive firms had fewer accidents compared to non-R&D heavy firms

· Longer tenured CEOs experienced fewer accidents, hypothesised due to CEOs becoming more familiar with their companies and cognisant of how to prevent those failures

· The effect was stronger in more accident prone industries compared to less accident prone industries such that overconfident CEOs had 4.4% fewer accidents overall and 2.17% fewer accidents per employees

· Overconfident CEOs had a greater impact on safety in states with relatively lax labour laws compared to states with more strict labour laws. According to the paper, this finding “implies that in states with strict labor laws, all CEOs are forced to invest more in worker safety. However, in states with weaker labor laws, where CEOs might otherwise underinvest, overconfident CEOs’ investment activities have the greatest impact” (p4).

· On the above, firms operating in strict labour law states experienced around 2.1% fewer accidents compared to firms in more lax labour law states (which highlights the impact of legislation).

Additionally, when firms were divided into groupings of being cash constrained or not cash constrained, overconfidence only reduced accidents in the cash constrained sample. Overconfidence in non-cash constrained firms had no statistically significant impact, being unsurprising since those CEOS could engage in significant CAPEX.

It’s said that even with cash constraints, overconfident CEOs continue to invest in CAPEX; further indirectly improving safety.

Moreover, unionisation was found to improve safety – more unionised states had 4.8% lower accidents compared to lower unionised states. Unionisation was found to offset the impact of overconfidence, possibly suggesting that unionisation forces non-overconfident CEOs to invest in safety enhancing actions.

Next they looked at the relationship that reduced accident risk has on higher labour productivity and thus higher firm value. It’s said that “accidents are negatively related to firm value and operating performance. This supports the notion that reducing accidents benefits both workers and shareholders due to the significant costs that those accidents can impose on firms” (p24).

Finally, authors address the question about what happens when CEOs change? They focus specifically on a non-confident CEO changing to an overconfident CEO rather than the reverse (since an overconfident CEO will have a lasting impact for months to years after they leave which will mask the true effect). A statistically significant reduction on accidents was found when a firm replaced a non-overconfident CEO with an overconfident CEO – reducing accidents by 6.35%.

Authors: Banerjee, Suman, Mark Humphery-Jenner, Pawan Jain, and Vikram Nanda,

Study link: https://acfr.aut.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/578752/Mark-HumphreyJenner-Environmental,-Soc-and-Gov.pdf

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/safety-first-overconfident-ceos-reduced-workplace-ben-hutchinson

SafetyInsights.org

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgRuthless Exploiters or Ethical Guardians of the Workforce? Powerful CEOs and their Impact on Workplace Safety and Health

This explored the association between CEO power and workplace injuries and illnesses.

Power was modelled via 1) structural power (whether the CEO has a dual role as chairperson and president) and their pay proportional to the five highest paid executives, 2) expertise, 3) ownership, 4) prestige. They also looked at geographical proximity of the CEO to employee injuries, since previous research has found favouritism towards employees in proximate locations.

It’s stated that powerful CEOs behave differently than non-powerful CEOs. CEOs gain utility by paying employees high wages which can create a better work environment and more loyal employees. They may also invest more in training, equipment and staff which may contribute to better safety performance. Rather than being solely for “truly altruistic reasons”, better safety performance may carry higher private benefits for CEOs for incentives and prestige and protect against takeover. Thus, “powerful CEOs can derive private benefits from behaving ethically” (p2).

They also argue and/or cite research highlighting:

- Powerful CEOs may have a poorer influence on safety since they create greater internal pressures to exceed earning targets (p2) and “firms that marginally beat analyst forecasts experience greater workplace injuries and illnesses, an increase in employee workload, and abnormal decreases in discretionary expenses” (p2)

- Powerful CEOS compared to nonpowerful CEOs may have compensation contracts less aligned with shareholder interest. They may thus be a liability for shareholders, but an asset to other stakeholders (like employees, who they may pay better)

- Research is mixed on the effects between the power of a CEO and corporate social responsibility (CSR). Some research shows that powerful CEOs engage in fewer CSR activities and may be more concerned with extending their own interests rather than other stakeholders, whereas other data found damaging effects of power on CSR was only found at the very high levels of CEO power. Another study found higher power was associated with better environmental activities.

- CEO power may enable the CEO to obtain private benefits at the expense of others (higher compensation), and higher compensation may be less linked to the performance of the firm. They may also be more likely to “rig incentive contracts” (p4), and less likely to be challenged after poor performance. Firms also may have higher variability in stock returns, suggesting that these CEOs act more unilaterally and involve other executives less often compared to less powerful CEOs

- However, firms with powerful CEOs may have higher relative valuation in industries operating in high-demand markets. This suggests “that powerful CEOs are particularly valued in firms that require rapid decision-making” (p4)

Results

Key findings in this study were:

- Firms with structurally more powerful CEOs have fewer employee workplace injuries and illnesses and fewer days away from work.

- Firms governed by a CEO also serving as chairperson have 1.75 fewer injuries and illnesses per 100 fulltime employees. Each 10% increase in CEO compensation in relation to the top 5 executives is linked to 0.40 fewer injuries per 100 FTE.

- Employees at firms where the CEO serves as the chairperson have fewer days away from work due to injuries/illnesses.

- However, firms governed by a company founder (ownership power) have a higher rate of employee injuries/illnesses (2.63 higher rate per 100 FTE compared to firms not led by a founder).

- Firms with structurally powerful CEOs mitigate differences in injury/illnesses rates in relation to geographical proximity to corporate headquarters (that is, less bias towards their own headquarter/home state).

- CEO compensation for health and safety was connected to better safety performance, but not solely due to compensation benefits.

Although more structurally powerful CEOs was linked to better injury/illness data in general – this wasn’t statistically linked to fewer fatalities.

Also, importantly, it’s noted that “improved” health and safety performance with more structurally powerful CEOs may also be confounded by underreporting; such that an alternative explanation “could be that powerful CEOs are using their influence to underreport workplace injuries and illnesses” (p19).

Overall, it’s suggested that “In contrast to the contemporary view that powerful CEOs are ruthless exploiters … we find, on average, that powerful CEOs are ethical guardians of the workforce” (p17).

Further, this study “suggests that powerful CEOs are better positioned to foster safe workplaces, and we thus inform practice of the bright side of powerful leaders” (p17). It’s reasoned that CEOs “derive a private benefit from low injury and illness rates”, and because of this, powerful CEOs are better at influencing organisational conditions to maximise benefit from this.

Authors: Jesper Haga, Fredrik Huhtamäki, Dennis Sundvik, 2021, Journal of Business Ethics.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04740-4

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ruthless-exploiters-ethical-guardians-workforce-ceos-ben-hutchinson

SafetyInsights.org

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgCEO speeches and safety culture: British Petroleum before the Deepwater Horizon disaster

This paper explored the relationship between CEO leadership language and safety at BP prior to the April 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion. Their main lenses are those of ideology and metaphor (via ‘CEO-speak’).

This paper is really detailed and dense, so I can’t do it justice.

Key data was the then CEO Tony Hayward’s Annual General Meeting (AGM) speech prior to the accident, and 18 other speeches from Heyward prior to the accident.

Note. This paper focuses on ‘safety culture’. Many like this concept, others struggle, but whatever. The paper is what it is.

Providing background:

- A focus on a unitary, organisation-wide ‘safety culture’ at BP, as promoted by leaders, was “rendered problematic” due to BP having numerous groups in heterogeneous work, with widely different safety risks, across already-existing legacy cultures from the broader societies and groups in which those people operate.

- Hayward’s replacement after the accident acknowledged that BP’s “safety culture” needed a shakeup. The Baker report (one group investigating the accident), for instance, mentioned safety culture 387 times.

- CEO-speak is “potentially a central formative element in developing a safety culture”, and CEO-speak can be conceptualised as anthropological because of “its importance in propagating and enabling ‘shared beliefs and values’ (an ideology) relating to safety” (p6).

- This view is said to be consistent with Schein’s view that “Culture is created by shared experience, but it is the leader who initiates this process by imposing his or her beliefs, values, and assumptions” (p6).

Results

· Overall, by analysing the CEO-speak, the authors identified that “the language used contributed rhetorically to an ideology of economic efficiency and cost control, in a manner that was inconsistent with an enduring safety culture”.

· Specifically, the CEO speeches emphasised particular accounting-related aspects in the narrative, like the tension between economic efficiency (including cost control) with a desire for a strong safety culture

· Moreover, while Hayward claimed that his “number one priority’ was safety, perversely ‘safety’ is hardly mentioned at all, while costcutting, financial matters, and organizational efficiency dominate”

· Hence, the CEO-speak tokenistically mentioned safety while focusing primarily on cost cutting, financial matters and organisational efficiency

For specific findings, the word ‘safety’ appeared only 17 times in Hayward’s 18 prior speeches to the 2010 AGM speech.

The authors state that the incidence of the word ‘safety’ appears to be low, considering “BP’s longstanding poor safety culture history”. Thus, they found little evidence for the notion that “the tone at the top was engaged actively in a normative discourse to promote a safety culture”.

When Hayward mentioned safety, it was coupled with:

· Referring to safety in a corporate project

· Safety of oil supplies

· And the title of a BP report

The word ‘culture’ appeared just four times and each “use is bereft of any link to safety”. The CEO prior to Hayward mentioned safety just 56 times, and ‘safe’ only 15 times across 125 publicly available speeches.

They also found use of language that seemed to separate safety, people and performance, such that “apparently regards safety as a separate, perhaps compartmentalised construct” – which is inconsistent with the view that safety culture is an integral constituent of an organisation’s culture.

While building core capabilities of people was mentioned, it was causally linked with safe and reliable operations, the focus on efficiency, and hence, “safety is made rhetorically subservient to” improved operational performance.

“Safety remains our number one priority” was also mentioned. However, this was measured almost solely by output measures, particularly financial. Of 24 performance measures mentioned in Hayward’s speech, just one involved safety (recordable injuries…meh). This is said to “sit oddly with the foundation concepts of safety culture”.

Further to the “number one priority” rhetoric, the word ‘safety’ is used only twice in the entire 2,323-word AGM speech. The text is rather dominated by financial and organisational efficiency.

Near the end of the speech, the first mention of the OMS (operating management system) is mentioned to be ‘fully implemented’. Hayward also “refers casually” to establishing a new culture at BP. It is unclear what this means, nor how this ‘new culture’ differs from the previous culture(s). It also lacks an appreciation of just how monumental trying to shift cultures can be.

The one-word metaphor ‘drive’ was used multiple times, highlighting the drive for efficiency. However, the authors argue that it is unlikely BP can “simultaneously drive down costs and improve safety, especially without acknowledging the complexity of constructing a safety culture in which every one in the company would have a common focus on greater safety at reduced risk”.

This view of culture presumes a “unitary, mechanical …organizational culture of a type that is unrealistic in a large global, high-risk company”. This draws parallel to the NASA ‘faster, better, cheaper’ organisational ideology – seen to be central in the Columbia shuttle accident.

Further, Hayward’s speech doesn’t draw on a “vocabulary of safety leading’ words, e.g. words like risk, hazard, maintenance, repair, prevent or accident.

As mentioned, the AGM speech is “dominated by a financial focus”, and there is “little genuine concern for ‘people issues’”.

Discussing the findings, the authors ponder on the leadership sensemaking that occurred prior to the AGM speech. Did the leaders believe they could genuinely achieve a focused drive on cost cutting and efficiency while prioritising safe and reliable operations?

Or, was this CEO-speak – that is, was Hayward “simply telling ostensibly gullible shareholders what he thinks they want to hear?”

Or, maybe this speech is an example of “corporate jingoism: a deliberately ‘upbeat account’”.

Frequency of spoken keywords are shown below:

Authors: Amernic, J., & Craig, R. (2017). Critical perspectives on accounting, 47, 61-80.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2016.11.004

Full version: https://pure.port.ac.uk/ws/files/6106863/CEO_speeches_and_safety_culture.pdf

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ceo-speeches-safety-culture-british-petroleum-before-ben-hutchinson

https://eprajournals.com/IJMR/article/6212

https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12432

https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/aaaj-04-2020-4519/full/pdf

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2024.101447

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/joom.1370

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2025.101056

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5231138

Meta-Analyses / Systematic Reviews / Interventions

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.827694/pdf

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2024.04.001

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09617353.2022.2035627

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2016.02.015

https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci14090212

SafetyInsights.org

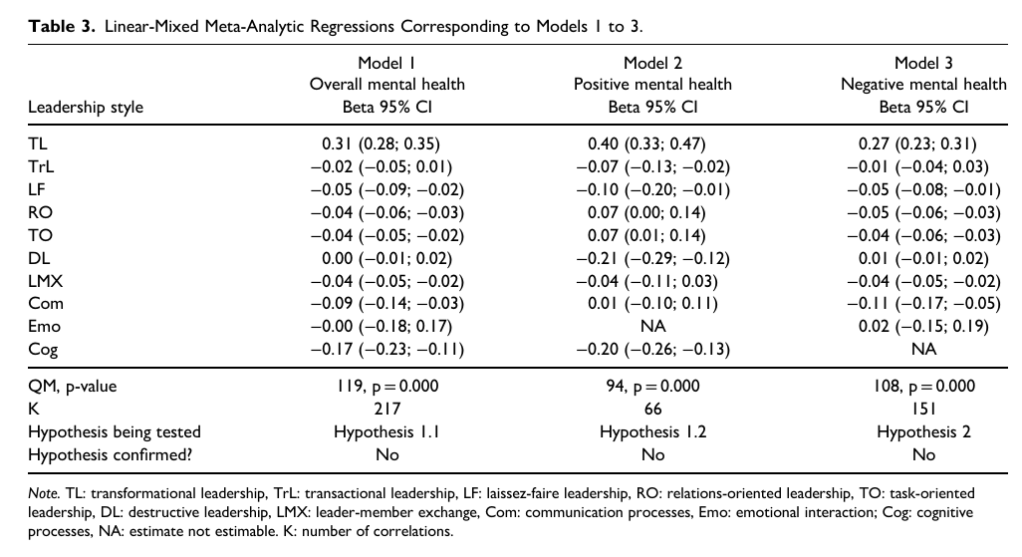

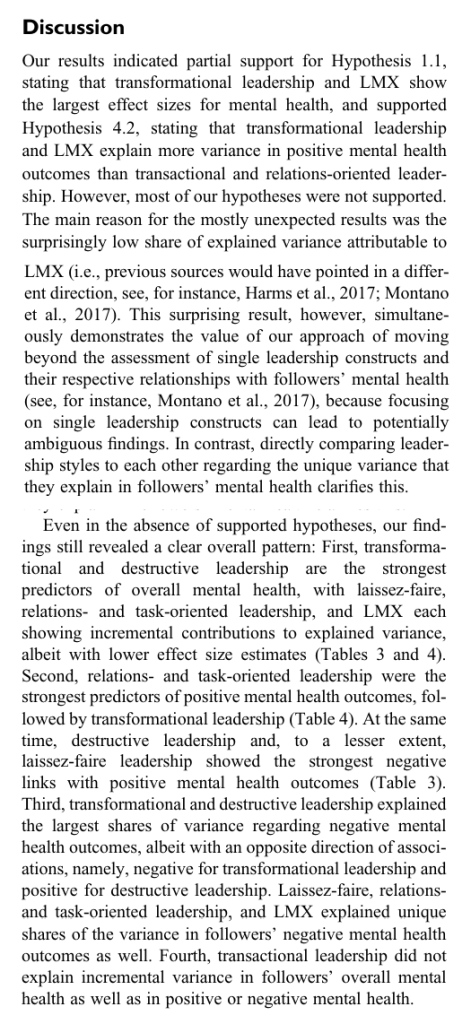

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgA Meta-Analysis of the Relative Contribution of Leadership Styles to Followers’ Mental Health

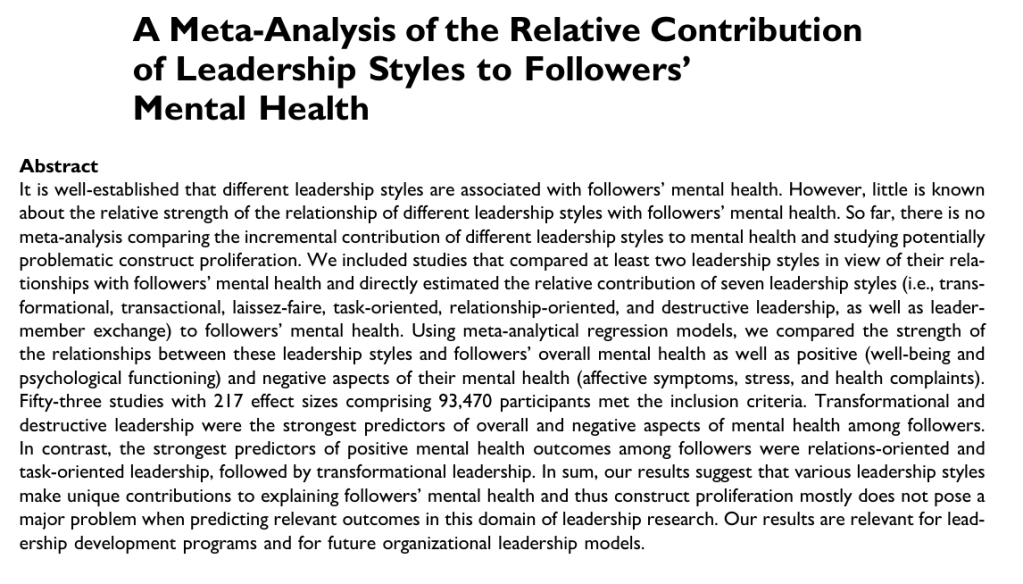

This meta-analysis of evidence on the contribution of leadership styles to followers’ mental health indices may interest you.

Not a summary – but you can freely read the full study.

53 studies with 217 effect sizes, comprising >93k participants met inclusion criteria.

They found that:

· Transformational and destructive leadership were the strongest predictors of overall and negative aspects of mental health in followers

· Relations-orientated and task-oriented leadership, followed by transformational leadership were the strongest predictors of positive mental health outcomes

· Transformational leadership and LMX had the strongest effect sizes for mental health; explaining more variance in positive mental health outcomes than transactional and relations-oriented leadership

· Laissez-faire, relations- and task-oriented leadership and LMX also showed incremental contributions to variance but with lower effect sizes

· Destructive leadership and to a lesser degree laissez-faire leadership showed the strongest negative links with positive mental health outcomes

· Notably, “Although the findings confirm the importance of transformational leadership for enhancing positive mental health and reducing negative mental health outcomes, destructive leadership is on a par with the predictive power of transformational leadership”

· Nevertheless, regarding all of the leadership constructs, there “is a substantial conceptual overlap with transformational leadership (cf. Judge & Piccolo, 2004). This overlap might also prevent the hypothesized augmentation effect, at least in view of mental health outcomes”

· They argue that the findings suggest that “leadership development programs can be optimized to favorably impact followers’ overall mental health by focusing on the core behavioral characteristics associated with transformational leadership”

· Moreover, “leadership trainings may also address the importance of an adequate balance between a clear definition of goals and work tasks and the building and maintenance of trustful, respectful, and considerate relationships with followers”

· And, “At the same time, given the large influence of destructive leadership or laissez-faire on mental health, leader development programs should also explicitly address potential antecedents and the detrimental consequences of those types of leader behaviors, and provide some guidance on appropriate policies and strategies to hinder or restrain their occurrence”

There’s a number of limitations, of course.

Ref: Montano, D., Schleu, J. E., & Hüffmeier, J. (2023). Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 30(1), 90-107.

SafetyInsights.org

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgExamining the impact of ethical leadership on safety and task performance: a safety-critical context

This studied the impact of ethical leadership on safety & task performance under the effects of two safety-critical factors:

1) perceived accident likelihood,

2) perceived hazard exposure.

Ethical leadership is defined as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement and decision making”.

A cross-sectional design was used collecting data from 397 workers.

Results

Findings indicated that there is a positive effect of supervisor ethical leadership, where “that workers who receive more ethical leadership produce higher safety performance and task performance than those who receives less or no ethical leadership”.

Specifically, supervisor ethical leadership had a positive correlation with safety participation, safety compliance & safety attitude; but only a relatively modest link with task performance.

Transformational leadership was positively correlated with ethical leadership & workers’ safety & task performance.

However, supervisor ethical leadership “did not moderate the ethical leadership–task performance linkage, which suggests that ethical leaders do not prioritize task performance (over safety performance) under high accident likelihood”. That is, the presence of ethical leadership isn’t effective in enhancing task performance under the presence of high perceived accident likelihood.

For high perceived hazard exposure, ethical leadership was more positively linked with safety attitude & task performance.

Practically speaking, the authors highlight the importance of leader behaviour on safety & task performance within firms. Further, focusing on “workers’ personality, awareness and knowledge of safety practices are not enough to achieve safety outcomes effectively”.

Specifically, in safety-critical environments workers seek direction, feedback & support from ethical leaders – such that ethical leaders can foster safety performance in environments of high perceived accident probability, and if job designs are less safety-critical, can also positively influence task performance.

Authors suggest that firms should promote ethical leadership behaviours among managers & supervisors.

Authors: Shafique, I., Kalyar, M. N., & Rani, T. (2020). Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41(7), 909-926.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2019-0335

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/examining-impact-ethical-leadership-safety-task-ben-hutchinson-6igkc

SafetyInsights.org

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgPassive avoidant leadership and safety non-compliance: A 30 days diary study among naval cadets

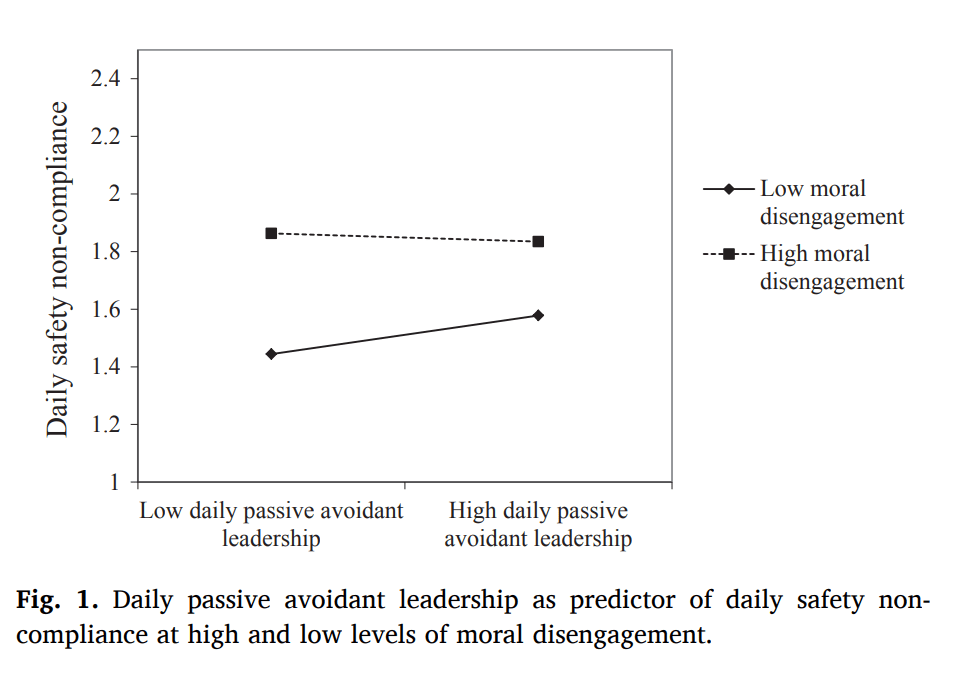

This study examined the malleable nature of safety compliance activities (adherence to procedures etc.) and how this can change on a daily basis with the impact of Passive Avoidant Leadership (PAL) styles. Laissez-faire leadership & management-by-exception are often referred to as PAL.

Also studied was the effects of moral disengagement (where people disengage from humane acts and commit to harassment or harming actions against others) and intolerance of uncertainty (being a dispositional tendency to perceive the occurrence of negative events as unacceptable or threatening, irrespective of whether they happen or not), where PAL may further exacerbate people who have high intolerance of uncertainty and thereby add to their stress.

PAL has been linked to adverse outcomes on work motivation, justice perception, burnout, psychological safety, safety climate and more.

78 naval cadets completed daily surveys during a 30 days voyage.

Results

49% of the variance in safety non-compliance related to variation within each crewmember from day to day, whereas 51% of the variation was between-person level. Thus, adherence to procedures etc. varied significantly on a day-to-day basis above & beyond what was explained by stable between-person differences.

Regarding PAL, a significant positive relationship between daily perceptions of PAL & daily non-compliance was found, where cadets engaged in significantly more non-compliances on days where they perceived their leader as more passive avoidant.

Daily PAL was said to be “particularly detrimental to breaches in safety compliance among those low on moral disengagement and among those low on intolerance of uncertainty. High moral disengagement and high intolerance of uncertainty, in contrast, buffer the negative impact of daily passive avoidant leadership on the cadets’ daily safety behavior” (p6).

Although people high on moral disengagement generally had more departures in procedures compared to those low in moral disengagement, they were less susceptible to the effects of PAL. In contrast, sailors low on moral disengagement were most vulnerable to rises in PAL regarding increased rule departures.

People low on moral disengagement may be more sensitive towards other’s well-being & rights and more personally challenged in moral situations relating to safety requirements. Thus prompting a stronger temptation to depart from requirements.

To quote, the “morally bad’ do not see a moral obligation, and are thus unlikely to change behavior, while ‘the good’ see, and thus, struggle to do what they ought to, particularly when no one are paying attention” (p6).

The authors discuss the malleable nature of safety activities and compliance. They note that it’s often studied as a static construct with stable between-people differences. However these results indicate that one-day snapshots are insufficient to learn about safety activity & compliance beliefs.

That is, “compliance” fluctuates day-to-day for each individual & the psychological processes within each crewmember is influenced by variables like emotions, social perceptions & situational factors that are partially unrelated to dispositions.

Findings are said to underscore the importance of not being perceived as a leader that is absent and avoidant during the day. They note that even relatively short periods of perceived avoidance may negatively impact safety perceptions at the workplace. Notably, the relationship between PAL & safety non-compliance was relatively weak, indicating that safety activity (and thus compliance) are influenced by multiple factors, with leadership being one amongst them.

Daily perceptions of transformational leadership didn’t explain daily variation in safety activities, which according to the authors suggests that “it is more important not to be perceived as passive and avoidant than it is to appear inspirational” (p6).

Authors say that the “theory of safety-leadership should emphasize both the malleable nature of safety behavior and safety leadership itself” (p6).

Authors: Olsen, O. K., Hetland, J., Matthiesen, S. B., Hoprekstad, Ø. L., Espevik, R., & Bakker, A. B. (2021). Safety science, 138, 105100.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.105100

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/passive-avoidant-leadership-safety-non-compliance-30-days-hutchinson-acqtc

SafetyInsights.org

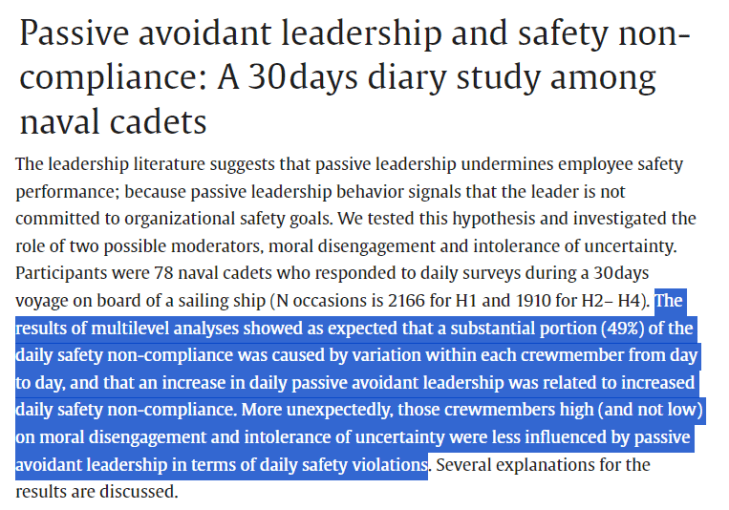

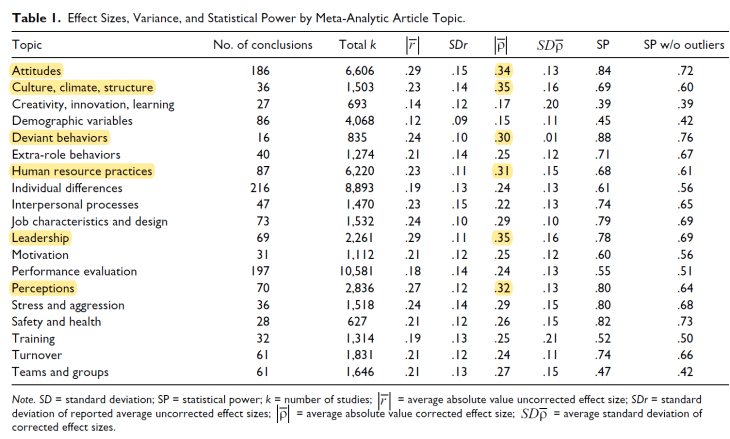

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgMeta-analysis of 30 years of management and HR constructs: leadership, culture, climate & structure the strongest predictors

Which management/HR concepts have the strongest impacts on organisational behaviour indices?

This 2016 study, impressively, compiled and calculated the pooled results from >250 meta-analyses from the past 30 years to answer this question.

This may be a useful reference for your own work.

Key tabulated results in the attached image (I’ve somewhat-arbitrarily highlighted the effect sizes in the 0.3 range). Higher p values = stronger effect sizes. Also, lower SDρ values give us more confidence in the values (this is adjusted standard dev), and higher SP & SP w/o outliers give us more confidence (statistical power).

The strongest adjusted effect sizes were for (in no particular order, but all within the 0.3 range)

· Attitudes

· Culture, climate, structure

· Deviant behaviours

· HR practices

· Leadership

· Perceptions

Stress and aggression and job characteristics and design both had effect sizes at 0.29.

Perhaps unsurprising, but leadership, culture, climate and structure variables had among the strongest effect sizes with three major dependent variables: job attitudes, performance, and turnover.

They argue that this finding “potentially provides evidence for the predictive strength of leadership theories and measures”.

However, they provide an alternate and more sceptical interpretation of leadership constructs: “that leadership’s high correlations with other variables is driven mainly by the fundamental attribution error. In other words, when workers are satisfied with their jobs they tend to overattribute this to their leaders” (p.72).

Demographic variables (gender, age, education level etc.), had the weakest relationships with other variables.

Other notably findings were that:

· Variables that are usually “other-rated” or objective tend to have smaller relationships with other variables, compared to self-reported variables

· The ‘file drawer problem’—publication bias, the selective reporting/publication of findings, usually positive findings—wasn’t found to be a significant concern in these data, i.e. “the file drawer problem is trivial, at least within the OB/HR fields”

· But other sources of bias and underpowered statistical sample sizes are present

Ref: Paterson, T. A., Harms, P. D., Steel, P., & Credé, M. (2016). Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 23(1), 66-81.

1) Study link: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1548051815614321

SafetyInsights.org

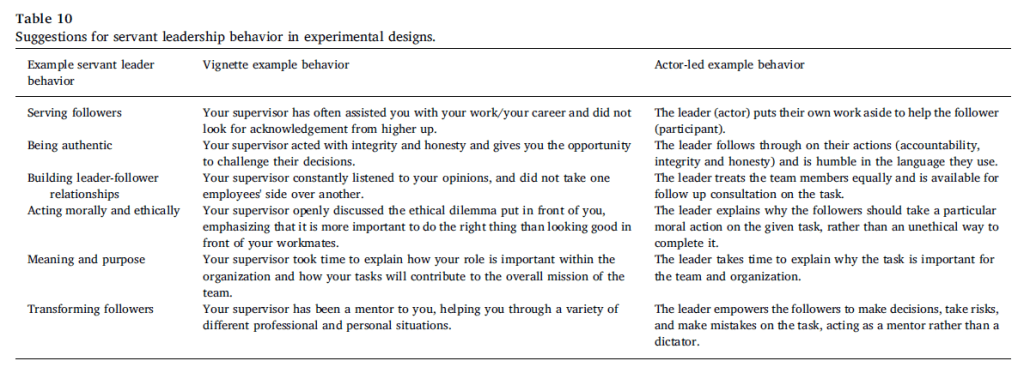

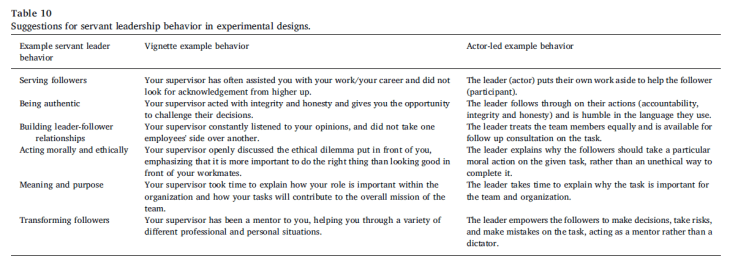

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgServant Leadership: A systematic review and call for future research

This reviewed the concept of Servant Leadership (SL) across 285 published articles over a 20-year period. It looked at conceptual clarity of SL and compared to other leadership concepts, and evaluated antecedents, outcomes, moderators and mediators.

SL is a leadership approach that engages followers in multiple dimensions (e.g. relational, ethical, emotional, spiritual) to help empower and grow their potential. SL is said to be a one-on-one prioritisation of follower individual needs and interests in order to achieve individuals’ and also organisational goals; which is based on the leader’s altruistic and ethical orientations.

SL is said to help fill a biological need where humans evolve from hunter-gatherer tribes, where we knew our leaders intimately. The Trade-off to large, bureaucratic organisations has said to leave a gap for our sense of belonging. SL is said to partially fill this gap by building a sense of social identify in followers (p111).

SL isn’t about being courteous or friendly, but rather, requiring a strong sense of self, character and psychological maturity – and be willing to serve others.

Results

SL was compared to other leadership approaches. E.g. Transformational leadership (TFL) and SL were found to have some common overlap with focusing on follower needs. However, SL is more focused on the psychological needs of followers as a goal in itself; whereas TFL places follower needs secondary to the companies.

Some research has shown that SL can “predict follower outcomes above and beyond [TFL]” (p113).

Similar to authentic leadership (ATL), SL also recognises the importance of authenticity. Yet, according to authors, SL may stem more from altruistic and deep self-awareness; this higher calling or conviction for serving others apparently being absent from authentic leadership concepts.

One study found that SL explained 12% greater incremental variance over TFL on follower outcomes (which was also larger than ATL (5.2%) and ethical leadership (6.2%); albeit with a small study.

From social identity theories, it’s said that as servant leaders focus on the growth/development of followers, followers feel obliged to reciprocate these positive leader behaviours. SL can enhance followers’ helping and organisational citizenship behaviours, commitment, trust and justice.

Regarding personality attributes of servant leaders, research showed that leaders high in agreeableness, low extraversion, high in core self-evaluation, high in mindfulness, and low exhibited narcissism all displayed higher levels of SL.

One study looked at relationship between emotional intelligence and SL, but no significant relationship was found.

Nevertheless, a limited body of research exists covering personality attributes and SL.

For gender, 2 studies found that relative to male leaders, female leaders are more likely to display behaviours of altruistic calling, emotional healing and organisational stewardship – which are similar in nature to SL. [ ** Although not sure how non-binary relate here, as this is rarely considered in research to date.]

SL was also linked with multiple job-related attitudinal outcomes, e.g. engagement, job satisfaction, perceptions of meaningful work and psychological well-being – and help reduce perceptions of emotional exhaustion, job cynicism and turnover intention. SL was positively related to helping behaviour, collaboration, self-rated corporate social responsibility and proactive behaviour.

SL was also associated with positive links to employee work-life balance and family support. Research suggests that “employees are more likely to view their organization positively in the presence of servant leaders” (p119).

For performance, SL is related to improved customer service, quality and performance; customer satisfaction, and customer-orientated prosocial behaviour. SL was linked to improved team effectiveness, psychological safety, creativity and innovation.

At the company level, SL has also been associated with better firm performance through service climate; and organisational commitment and operational performance.

Importantly, there may have been publication bias where most published studies had their hypotheses confirmed. Non-significant moderators tended to be at the company level. However, the authors hypothesise that perhaps the impacts of SL may not be “affected by distal organizational policies, procedures, and environments, as servant leader creates their own strong, service based-culture within their team” (p122).

Evidence supports selecting and training leaders to practice SL.

It’s also recognised that SL is well-suited for companies that desire long-term growth to benefit all stakeholders. Further, SL has an indirect influence of company outcomes – but helps followers to reach their full potential, becoming empowered to handle (p128).

However, some significant gaps in the evidence still exist for SL. For one, it appears research covering boundary conditions and/or unexpected negative effects of SL is limited.

The paper provides some examples of what SL can look like in practice:

Authors: Eva, N., Robin, M., Sendjaya, S., Van Dierendonck, D., and Liden, R. C. (2019). The leadership quarterly, 30(1), 111-132.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.07.004

Link to the LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/servant-leadership-systematic-review-call-future-ben-hutchinson

SafetyInsights.org

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgLeadership training as an occupational health intervention: Improved safety and sustained productivity

Abstract

The safety climate in an organization is determined by how managers balance the relative importance of safety and productivity. This gives leaders a central role in safety in an organization, and from this follows that leadership training may improve safety. Transformational leadership may be one important component but may need to be combined with positive control leadership behaviors. Leadership training that combines transformational leadership and applied behavior analysis may be a way to achieve this.

Purpose: The study evaluates changes in safety climate and productivity among employees whose leaders (n = 76) took part in a leadership training program combining transformational leadership and applied behavior analysis. Changes in managers’ ratings of transformational leadership, contingent rewards, Management-by-Exceptions Active (MBEA) and safety self-efficacy were evaluated. Moreover, we compare whether the training has differentiated effects on safety depending on managers’ specific focus on improvements in: (1) safety, (2) productivity or (3) general leadership.

Result: Safety climate improved over time, while self-rated productivity remained unchanged. As

hypothesized, transformational leadership, contingent rewards and safety self-efficacy as proxies for positive control behaviors increased while MBEA, a negative control behavior, decreased. Managers focusing on general leadership skills showed greater improvement in safety climate expectations.

Conclusions: Training leaders in both transformational leadership and applied behavior analysis is related to improvements in leadership and safety. There is no added benefit of focusing specifically on safety or productivity.

****

Other findings from the full-text paper:

1. It was found that the perceived priority of safety could be increased without negatively affecting employee ratings of productivity.

2. This finding may be related to leaders being better able to manage multiple demands to avoid unintended consequences on performance.

3. Perhaps an advantage of more general training is that it permits leaders to practice handling multiple objectives. The authors suggest that another advantage of general leadership training is that it may allow leaders who have little interest in safety training to still significantly and positively impact safety.

Supporting point 3, other research suggests that a focus on low-fidelity simulations (ones that do not have high photorealism of the environment and task) and more generalised skill training can also improve learning by developing their ability to deal with uncertain situations and thus develop problem-solving skills which can be applied to more situations (e.g. resilient skills).

Also, there seems to be a fragmentation of several organisational concepts in safety (e.g. ‘safety culture’ over organisational culture, ‘safety leadership’ over general leadership). These findings I believe, alongside research on emergent and complex adaptive systems and the criticisms of ‘safety culture’, lend further support to the notion of considering how the entire organisation, its people, subcultures, systems and technology interact and make sense of risk as an emergent property instead of deconstructing into parts.

Authors: Ulricavon Thiele Schwarz, Henna Hasson, Susanne Tafvelin, 2016, Safety Science

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2015.07.020

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/leadership-training-occupational-health-intervention-ben-hutchinson

SafetyInsights.org

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgDo happy leaders lead better? Affective and attitudinal antecedents of transformational leadership

Abstract

In a study of 357 managers using multiple methods and raters, we investigated how leaders’ affective experience was linked to their transformational leadership. As predicted, we found that leaders who experienced more pleasantness at work were rated by their subordinates as more transformational, and this relationship was partially mediated by leaders’ affective organizational commitment. Surprisingly, job satisfaction did not mediate this relationship. Theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

****

From the full-text paper:

- “leaders who experienced higher levels of pleasantness at work were indeed rated by subordinates as more transformational in their leadership” (p74)

- “leaders who experienced higher levels of pleasantness at work reported significantly higher levels of job satisfaction … and affective organizational commitment” (p74)

- “leaders who reported feeling more committed to their organization were indeed rated by subordinates as more transformational in their leaders” (p74)

- “the extent to which leaders engage in transformational leadership is significantly influenced by the extent to which leaders experience pleasantness at work” (p77)

- “the extent to which leaders feel affective organizational commitment partially accounts for why more transformational leadership tends to be engaged in on the part of leaders with more pleasant affect at work” (p77)

- “job attitudes are “not equal” in their potential to account for affect-leadership relationships; this is because we found affective organizational commitment but not job satisfaction to partially mediate the tendency for more positively-affected leaders at work to engage in transformational leadership” (p78).

Regarding practical implications, the authors suggest that:

- How leaders are treated (and not just the way leaders treat subordinates) appears to be an important factor in determining the likelihood of transformational leadership. Thus, the authors state that “treating organizational leaders well so that they experience more pleasant feelings at work in an ongoing manner may be key in determining how transformational leaders will be” (pg.80).

- Therefore, leaders may not regularly engage in transformational leadership unless they are happy at work.

- The degree of leaders’ affective organisational commitment may be another critical factor in the likelihood of them engaging in transformational leadership. This led authors to suggest that “organizations can consider various other ways to increase leaders’ affective organizational commitment in order to promote transformational leadership.”

Finally, another interesting suggestion from the authors was that:

- “The importance of more organizationally-committed leaders in fostering transformational leadership in organizations also suggests that it is time for organizations who seek transformational leaders to do one of two possible things: (1) consider actions other than selection (e.g., identifying leaders with certain personality types or individual traits) and/or (2) supplement selection-strategies with actions that increase the affective organizational commitment of the individuals they seek as transformational leaders” (pg.80).

Authors: Jin, S., Seo, M., & Shapiro, Dl.L. (2015). The Leadership Quarterly

Study link: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.09.002

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/do-happy-leaders-lead-better-affective-attitudinal-ben-hutchinson

SafetyInsights.org

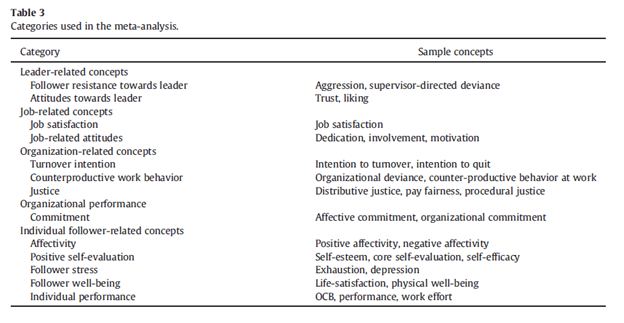

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgHow bad are the effects of bad leaders – A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes

This meta-analysis evaluated research on the impacts of destructive leadership on organisational, individual, job-related outcomes; highlighting the strength of the correlations. 57 studies (out of 200+ identified) met inclusion requirements.

Way too much to cover, so just a few points.

First, they give a background on destructive leadership. Prevalence of destructive leader behaviours have been identified in 11% of workplaces in one European study, in a third of all surveyed employees in another study, and ~14% in the US.

Second, they differentiate between destructive leader behaviour and destructive leadership. There’s no clear consensus here, but they argue that destructive leader behaviours is a broader concept with more harmful behaviours that aren’t necessarily related to leadership (e.g. drug taking at work), whereas destructive leadership focuses on those aspects which are primarily targeted towards followers.

They define destructive leadership as “a process in which over a longer period of time the activities, experiences and/or relationships of an individual or the members of a group are repeatedly influenced by their supervisor in a way that is perceived as hostile and/or obstructive” (p141). Thus, leaders use destructive leadership practices to achieve certain aims and/or influence the activities and relationships within follower groups.

Finally, destructive leadership is different to negative leadership traits, like laissez-faire, or anti-organisational behaviour.

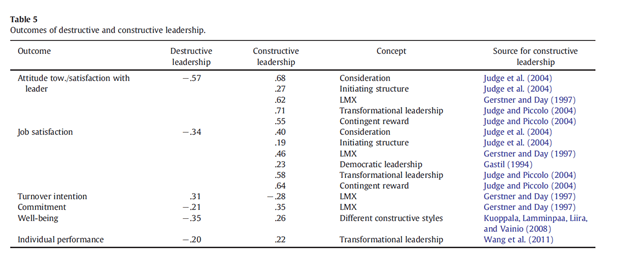

The table below covers the categories of destructive leadership covered in the analysis.

Results

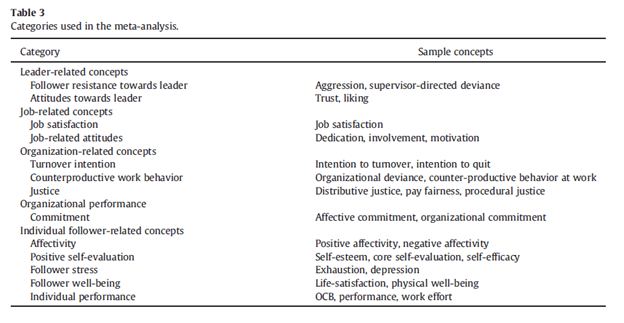

Not surprisingly, destructive leadership is negatively related to positive leader-related concepts and positively related to negative leader-related concepts.

Destructive leadership also had negative associations with positive organisational concepts and positive job-related aspects, and individual facets (as per the table above).

The strongest effect found was towards follower attitudes towards the leader, “indicating that destructive leader behavior is directly related to how followers feel about their leader” (p146). Despite this strong correlation, the relationship between destructive leadership and follower resistance towards the leader, while still having a strong & statistically significant effect, is weaker than some other relationships. This may indicate “that attitudes maybe more strongly affected by destructive leadership than behavior, at least where the leader is directly concerned” (p146).

The second strongest effect was found with counterproductive work behaviour. They suggest that while direct resistance towards the leader via obvious behaviours may be risky regarding punishment and retaliation from the leader (as the above paragraph highlighted that attitudes were more impacted), counterproductive work behaviours may be a more clandestine way for followers to “retaliate upon one’s leader for his destructive leadership” (p147). The use of more clandestine counterproductive work behaviours may be a way to pay back destructive leaders while minimising a further “spiral of abuse” (p149).

Job-related concepts including job satisfaction and organisational concepts like turnover and experience of justice had medium-sized correlations.

Some of the correlations of the higher categories are shown below (the full list of correlations are in the paper). The correlations between constructive leadership and outcomes were generally stronger than the effects of destructive leadership [which is probably worth a separate study/post in itself].

The impacts of destructive leadership spill over outside of work-related facets, worsening perceptions of well-being, negative affectivity and stress. The relationship with stress was weaker than the other two factors, hinting that destructive leadership may more strongly impact a persons’ well-being and negative emotions more than their perceived stress; with stress, people may be able to adopt other coping mechanisms, such as sharing load with co-workers and the like.

They note that destructive leadership also impacted organisational commitment, follower positive self-evaluation & individual performance, which are all influenced by a wide range of factors outside the control of the leader. Nevertheless, “it is still striking that destructive leadership has an effect even on those aspects of their followers’ lives” (p148).

In discussing the findings, it’s said that at least initially, destructive leadership might work for achieving goals and that some research found that goal setting “can contribute to the emergence of destructive leader behaviors”. In that sense, some leaders may be using those techniques to achieve goals.

Followers of destructive followers not just have worsened attitudes to the leader or their work, but also another spillover effect towards the organisation as a whole. It’s argued that peoples’ experience of organisations may in a sense mirror their experience of their destructive leader and also because of a “perception that the organization does not intervene to protect their employees” (p149).

Expectedly, this spiral impacts staff turnover and likely a drop in performance.

The very strong relationship between destructive leadership and counterproductive work behaviours is said to be particularly worrisome. They discuss three reasons for the high correlation.

- The relation effect from followers towards the leader, which provides followers with a safer course of action against them (called ‘displaced deviance’).

- The role modelling influence of leaders may convey the message that this type of behaviour is acceptable within the organisation.

- Potentially indicative of more general organisational cultures which tolerate these types of negative behaviours.

Authors: Schyns, B., & Schilling, J. (2013). The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 138–158.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.09.001

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-bad-effects-leaders-meta-analysis-destructive-its-hutchinson

SafetyInsights.org

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgReducing workplace accidents through the use of leadership interventions: A quasi-experimental field study

This studied the effects of training supervisors in leadership (LX) theory around transformational (TFL) and active transactional behaviours (TSL) on leadership behaviour, safety climate, employee safety behaviours after a 8-week period.

TFL emphasises inspiring and motivating leader behaviours; which in turn, encourages employees to engage in higher levels of safety participation and noted to build consensus among employees’ perceptions of the priority given to safety (pg.315).

TSL emphasises proactive monitoring and correcting leader behaviours, meaning leaders can better anticipate problems and take proactive corrective actions. It’s noted that “this form of leadership promotes learning in how to anticipate and prevent safety incidents and adverse events” (p315).

Some other relevant findings include:

- While there’s increasing calls for leaders to use a combination of both leader behaviours, few studies (when this study was published) had evaluated the combination

- A meta-analysis found that TFL was universally effective, but TSL was found to vary in effectiveness, suggesting the influence of contextual moderators

- TSL may be more appropriate in the context of safety-critical environments, represented by complexity and uncertainty, since it “focuses on providing clear guidance and feedback” (p315)

- Another meta-analysis found that leadership interventions were generally effective in changing leader behaviours and particularly when aimed at the supervisory level, e.g. a half-day workshop on TFL techniques for supervisors led to employees reporting a higher increase in TFL leader behaviours 3 months later

- Other more mixed findings were found in other studies

Results

Both LX types were found to be effective in helping supervisors to apply both techniques to behaviours of safety, although no change in the frequency of the behaviours was found. TFL was found to already be high and already linked to safety pre-intervention, whereas TSL behaviours were only increased & linked to safety after the intervention.

Although the frequency of technique behaviours did not increase (against predictions that leader safety behaviours would change), TSL became better aligned to safety outcomes post-training; suggesting coaching leaders on how to apply context-sensitive LX skills, rather than just the frequency.

As per previous work, TFL was more closely linked employee safety participation & TSL more strongly to employee compliance.

Training led to significant improvements in perceived safety climate, compared to the comparison group (who received no training). Further, re-orientating TSL behaviours towards safety goals can improve employee safety perceptions, including perceptions around management commitment, communication and work pressure.

Interestingly, even though leader behaviour didn’t significantly change post-intervention, they highlight previous research suggesting that “moderate (rather than high) levels of transformational and active transactional behaviors were most associated with safety; thus interventions that focus on increasing the frequency of such behaviors beyond this level may not be optimal” (p319).

Although no change was noted in employee behaviour (only perceptions) – the authors suggest this may take longer to emerge and that “it is likely that employees become more receptive to active transactional behaviors in high-risk contexts, rather than leaders spontaneously adjusting their behaviors to match the situation” (pp318-319).

Finally, the findings suggest that training interventions do not need to focus on any particular LX style, but combinations and general LX theory is effective.

[Note: Although not discussed in this study, other research has countered this view somewhat be suggesting better improvements with domain-specific leadership styles targeting the specific goals of interest; e.g. safety leadership for safety matters, sleep leadership for sleep behaviours etc..]

Finally, these findings “suggest that safety leadership interventions might focus more on the orientation of leader behaviors relative to the situation (e.g., learning how to use active transactional behaviors, such as proactive monitoring, to improve safety compliance), rather than frequency of behaviors” (p319).

Authors: Clarke, S., & Taylor, I. (2018). Accident Analysis & Prevention, 121, 314-320.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2018.05.010

Link to the LinkedIn summary: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/reducing-workplace-accidents-through-use-leadership-field-hutchinson

SafetyInsights.org

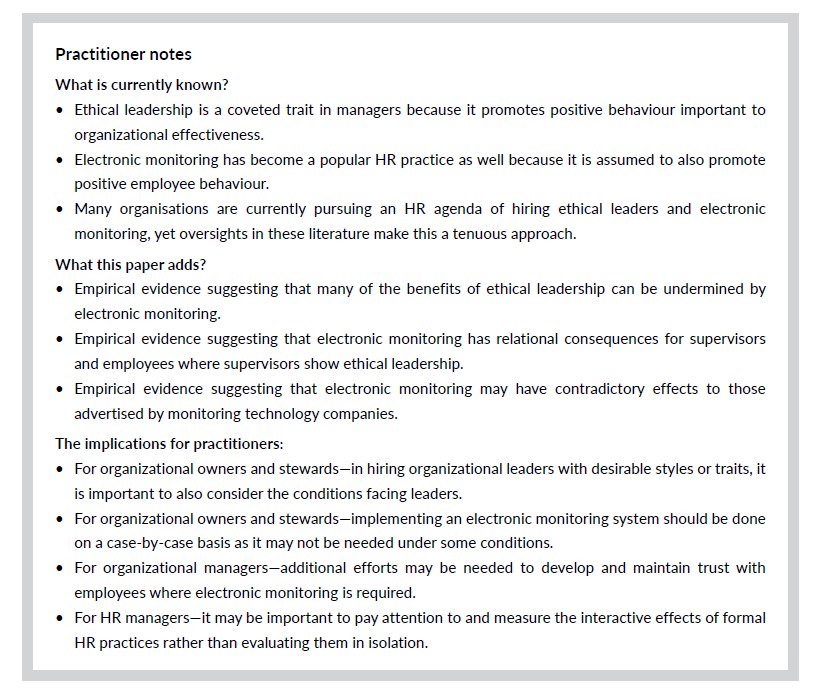

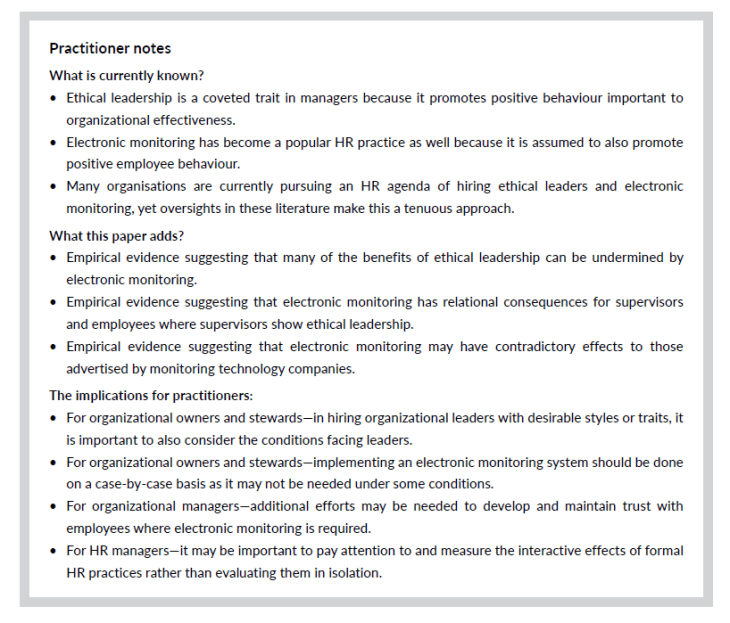

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgThe (electronic) walls between us: How employee monitoring undermines ethical leadership

This explored the role employee electronic monitoring (EM) plays in undermining ethical leadership by eroding trust. Data was via survey from a diverse field sample of supervisors and their employees.

Providing background on ethical leadership and employees, it’s said:

- Employees of ethical leaders perform their expected duties more effectively and ethically but also speak up when they observe workplace issues

- Employees of ethical leaders (EL) also undertake more organisational citizenship behaviours

- These effects result, in part, because ethical leaders typically form strong relationships with their employees and “thereby inspire ethical behaviours through social exchange processes” (p1).

Relating to EL and EM:

- Some prior research shows that monitored individuals “perform assigned tasks more efficiently … commit less deviance … and engage in more OCB … despite employee objections” (p2)

- Nevertheless, organisation’s on one hand emphasise ethicality in the hiring process and appraisal of supervisors and on the other hand “[subject] their employees to electronic surveillance … such as desktop software-based monitoring” (p2). EM also includes GPS-tracking, biometrics, video and more.

- EM is an “organizational control system involving the use of technology to observe, track, and evaluate employee behaviour” (p5) and some data indicates that >80% of large global companies electronically monitor employee performance

- Employees have reported a dislike, frustration, feelings of injustice and dissatisfaction towards EM and “decrying the choice-limiting, privacy-robbing, and coercive nature of the HR practice” (p5)

- It’s reasoned that because of how EM is perceived by employees, it will seek to undermine and erode the relationships between supervisors/leaders and their teams. Thus, challenging the very underlying principles of ethical leadership.

Results

Core findings included:

- “an ethical supervisor’s ability to positively shape employees is weakened by EM because monitoring erodes the trust their employees experience” (p11)

- Organisational conditions created through HR policy, like monitoring, can “undermine good relationships fostered by positive leadership” (p11)

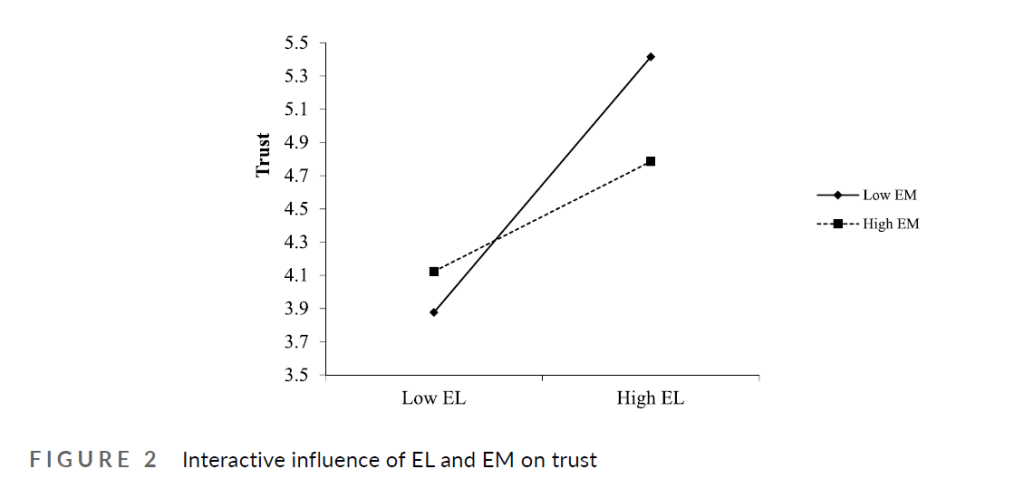

- As expected, when EM was low, the relationship between EL and trust was positive and significantly related. When EM was high, the relationship between EL and trust was still positive but significantly smaller (shown in the graph below)

- The indirect relationship between EL and employee voice through trust was significantly larger when the EM was low compared to when EM was high

- Likewise, employee citizenship behaviour was larger when EM was low compared to high

They also found that monitoring had no direct effect on employee trust in their supervisor, since trust only emerges if the leaders offer social benefits to followers.

Notably, while monitoring may be implemented to decrease deviance and try to enhance ethical behaviour, it “may paradoxically undermine the very behaviours it is designed to promote when employees are already supervised by an ethical leader” (p11).

Indeed, they argue that for organisations who are pursuing the hiring and development of ethical leaders, EM may do more harm than good. This is said to make sense because ethical leaders bring about positive outcomes through fair treatment humane employee conditions and thus introducing controversial practices like EM “would likely seem contradictory to employees” (p12).

If organisations want to keep using EM, the authors suggest it should be used on a case-by-case basis, since it may make sense in some conditions but not others (like when ethical leaders are already in place).

Further, the authors suggest that companies should either commit to “the hiring of ethical leaders and the fostering of an ethical culture … or EM, but not both” (p12, emphasis added) and further these approaches “are not complementary, as some may think” (p12).

Ethical managers who have no choice in EM should take proactive steps to mitigate the negative effects.

Authors: Thiel, C. E., Prince, N., & Sahatjian, Z. (2022). Human Resource Management Journal. 022;1–16.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12462

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/electronic-walls-between-us-how-employee-monitoring-ben-hutchinson

SafetyInsights.org

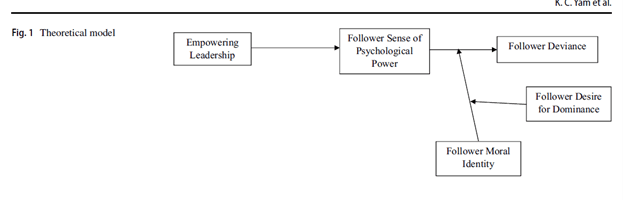

safetyinsights.org@safetyinsights.orgThe Unintended Consequences of Empowering Leadership – Increased Deviance for Some Followers

This study explored the impact that empowering leadership can have on worker deviance. Two studies were ran – one field study and a second lab study.

Providing background, they note:

· Deviance is voluntary behaviours that violate organisational norms and which threaten the well-being of the organisation and/or its members

· Empowering leadership is “the process of implementing conditions that enable sharing power with an employee” (p1)

· Research has shown the positive effects associated with followers of empowering leaders, including higher creativity, happiness and commitment

· Empowering leadership involves behaviours like mentoring, delegating responsibilities and removing bureaucratic restraints at work

· By doing so, empowering leadership can result in a “a heightened sense of psychological power” among followers; where followers have more intrinsic task motivation and sense of control in their work and a higher perception of being able to influence others

· People with greater power are more likely to focus on their self-interests, ignore the interest of others and more likely to behave more unethically (p2)

· On the above, having more power doesn’t automatically lead to higher deviance but rather deviance in the powerful seems to relate strongly to the individual’s prosocial attributes, namely: strength of moral identity and their desire for dominance

· Moral-identity is a self-conception around moral traits. People with higher moral identity are “more attuned to the content of their daily lives, which helps mitigate immoral behavior” (p4)

· Desire for dominance is a self-serving behaviour, where people control others and the nature of work/decisions for self-interested goals

· Thus, higher empowering leadership may cultivate worker deviance in the workplace but primarily in those who have a weaker moral identity and a strong desire for dominance

· In support of the above, they cite research highlighting that compared to “powerless men, powerful men were more likely to objectify women, but only when they had a disposition toward sexual harassment” (p.4). Further, when people had natural inclinations to focus on the needs of others, their power was more positively associated with more generous behaviour

An important reason for this research, according to the authors, is that most of the research on empowering leadership has focused on the positive facets and not any negative effects. This study, among others, study the boundary conditions of common concepts.

Their model of the associations between empowering leadership, prosocial attributes and deviant behaviour is shown below:

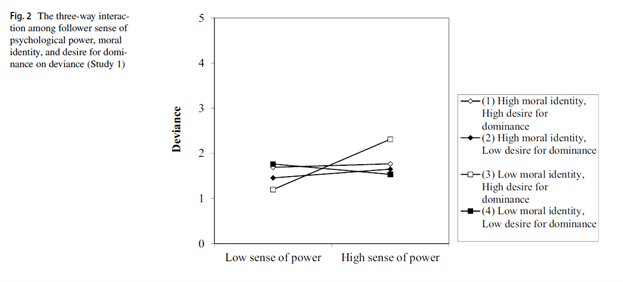

Results

Overall, the findings demonstrated that “compared to the followers of less-empowering leaders, the followers of more empowering leaders feel subjectively more powerful and engage in more deviant behaviors” (p1).

Further, they found that “the propensity of empowered followers to engage in more deviance depends on their prosocial attributes” and specifically, “empowered followers engage in the highest levels of deviance when they have a weak moral identity and a strong desire for dominance” (p1).

That is, empowering leadership doesn’t automatically increase follower deviance but rather it can/does when followers have either a weak moral identity or strong desire for dominance.

Thus, while empowering leadership can increase productivity and employee engagement, it may “also cultivate harmful effects” (p1) and, like anything, is itself “not a panacea” (p12).

In describing negative effects of empowering leadership, they go to lengths to clarify that they “nevertheless believe that empowering leadership very likely exerts a positive net effect to their followers and organizations” (p12).

Further, empowering leadership is “still primarily a positive leadership style that leaders should adopt, and that it is only a double-edged sword for a minority of followers” (p12).

This study is among a cadre of others which cover boundary conditions of concepts that, hitherto have mostly focused on positive effects (which includes other styles of leadership and psychological safety which also have boundary conditions and potentially negative effects in some instances).

Authors: Yam, K. C., Reynolds, S. J., Zhang, P., & Su, R. (2021). Journal of Business Ethics, 1-18.

Study link: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04917-x

Link to the LinkedIn article: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/unintended-consequences-empowering-leadership-some-ben-hutchinson

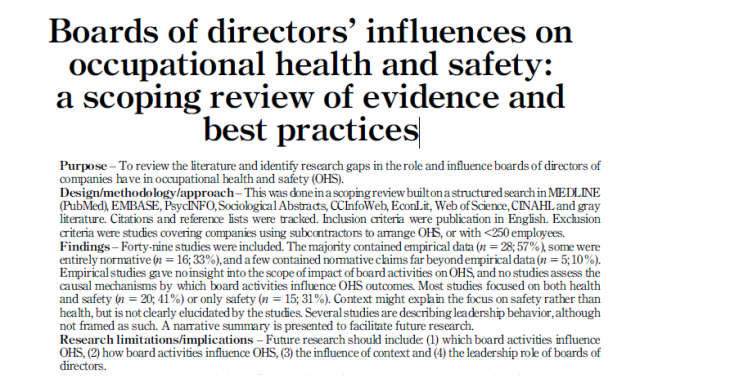

Boards of directors’ influences on occupational health and safety: a scoping review of evidence and best practices

This literature review evaluated the impact of boards of directors on workplace safety.

49 studies met inclusion.

Way too much to cover.

Background:

· “There is a growing understanding that operative leadership, from line managers to senior management, plays an important role in occupational health and safety”

· Leadership “do not act in a vacuum” and are influenced by the organisation, including from senior management, who themselves are responsible for setting agendas and resources

· They highlight that while there is quite a bit of research in this area, “all of these descriptions of roles and responsibilities focus on operative management (the day-to-day running of a business), rather than strategic leadership and governance; that is, the system by which an organization is directed and controlled”

· And “The body responsible for strategic leadership and governance is the board of directors”

Results

Key findings:

· “Empirical studies gave no insight into the scope of impact of board activities on OHS, and no studies assess the causal mechanisms by which board activities influence OHS outcomes”

· “Most studies focused on both health and safety (n 5 20; 41%) or only safety (n 5 15; 31%)”

· “Context might explain the focus on safety rather than health, but is not clearly elucidated by the studies”

· “Several studies are describing leadership behavior, although not framed as such”

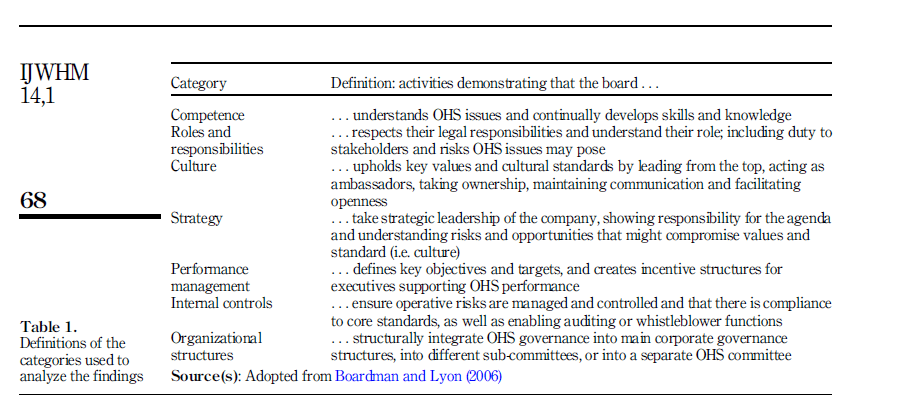

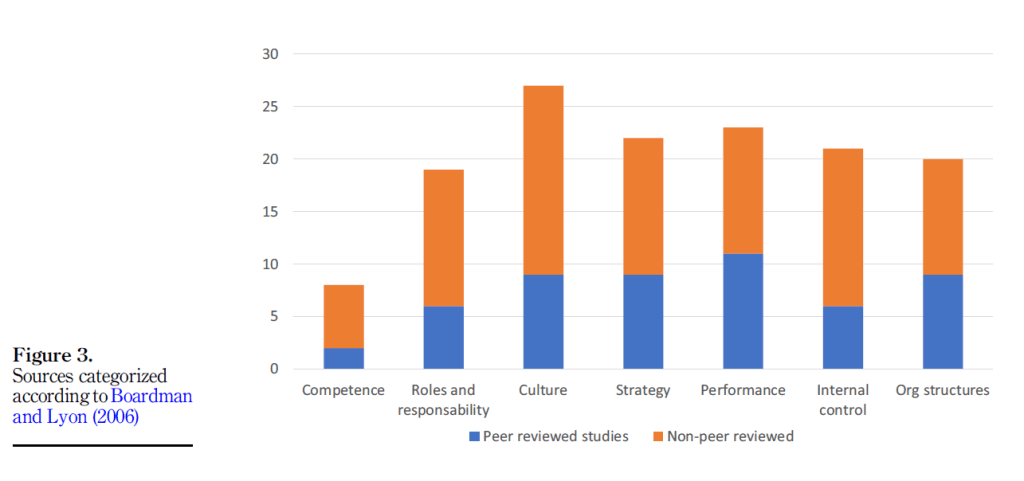

They categorised the frequency of topics that research focused on:

A random assortment of other findings were:

· Based on the 49 studies, they found that 57% contained empirical data, others were entirely normative (33%), and a few “contained normative claims far beyond empirical data”.

· Most of the sources focused on both heath and safety (41%), or only safety (31%).

· Board-level governance of OHS was more common in top-performing companies, and board-level involvement “was motivated by a need for power and control, mandated by legislation or based on a need for corporate governance”

· One source indicated that boards get involved with OHS issues was for reasons beyond just liability, and included things like a duty towards stakeholders or pride in achievement

· The overarching categories of a boards’ OHS responsibility were grouped under planning, delivering, monitoring and reviewing by some sources

· One safety manager remarked that “the responsibility of boards was not to “drive” safety, but to make sure that managers do so”

· For how boards should organise responsibilities – some sources said for there to be one nominated director for developing and monitoring safety, other work suggested that the CEO should automatically be the nominated safety director, and others disagreed

· They note “Although having an assigned “director of OHS” can provide a strong signal that OHS is a

· prioritized issue (Hughes and Ferrett, 2011), it also risks that person becoming a scapegoat for failures … or increases the risk of power struggles between board members with different areas of responsibilities”

· Some work suggested that safety should be integrated into other areas of a boards’ responsibilities, in order to create synergies and improve knowledge management, whereas others argued against this approach eg “such an integration may increase the risk of OHS work becoming completely subsumed by other focus areas”

· Sources identified the need for directors to have a basic understanding of OHS, and to understand their legal and formal responsibility – especially the chairperson

· Interestingly, quoting the paper “a Canadian study found no evidence that members of OHS committees had any formal OHS education/qualification, and its authors argued that such a lack of competence would never be accepted in, for example, a financial subcommittee” (emphasis added)

The paper unpacked a few other areas. Boards would focus on culture & strategy of safety. However, the research in this area was highly focused on defining and “captur[ing] culture”, rather than on how boards actually influence cultural elements. Also, a lack of OHS was seen as a threat to daily operations.

Boards also focused on performance management. Some sources suggested that boards should establish key objectives, KPIs, incentives and more relating to safety.

From what I can tell, the recommendations on indicators were the usual suspects – leading/lagging, strategic/outcome/process and more.

Some sources related strategic to culture and less tangible elements of performance; outcome measures were absences from work and the like; process measures include training measures, perception surveys [*** and probably control effectiveness, system effectiveness etc?]

They say “Overall, several sources suggested mixing quantitative and qualitative indicators, covering tangible and intangible aspects”.

Some sources covered OHS incentive structures. Usefully, some of this work pointed out the potential unintended consequences of incentives, e.g. “A performance measurement system should pay attention to the potential trade-off between OHS and other indicators such as financial performance”.

Also, usefully, some work pointed out the difference between “what is easy to measure and what is important to measure” (emphasis added).

Some studies concluded that boards should oversee how organisations manage OHS and how they go about managing and controlling risks – including operational risks, accidents, health claims, legal risks and psychosocial and physical risks.

It’s recommended that the “system for internal controlcshould be harmonized between different divisions of an organization and with its performance management system”. Internal controls to the board should be based on regular reports to the board, including both internal and external sources.

Another source recommended independent reviews twice a year, another suggested reports on OHS at every board meeting, monthly, and/or whenever something bad has happened. Other sources suggested that internal controls to boards should include audits or reviews, diligence reports and statistical data.

Some sources also recommended that boards receive details on major risks and “reporting according to a certain theme (such as safety culture, vehicle risks or plant maintenance; Peace et al., 2017)”.

Other work commented on the structures of board OHS oversight. Some saw that OHS should be integrated int the board meeting or existing subcommittees, whereas others advised the establishment of a separate subcommittee for OHS.

Some data found that firm performance was better with the presence of separate subcommittees that focused on specific performance outcomes (at least in sustainability). Another study “could not find conclusive evidence that OHS committees improved OHS, although 90% of members of the committees were convinced that they did strongly improve [performance]”.

Nevertheless, subcommittees are argued to play an active role in creating an “open culture”, and they can “be an important motivator for executives to engage in OHS”.

Discussing the findings, they argue that:

· “The literature mostly focused on the boards’ role in organizational culture, whereas the role of the competence of boards of directors was least discussed”

· Boards were far more frequently involved in safety than to worker health

· It’s said that “the one-sided focus on safety poses a challenge to theory and practice”, as work-related health issues are “increasingly dominated by psychosocial health issues”

· Boards may face some challenge with psychosocial matters compared to their focus on physical safety

· This is because “an injury can more often be directly associated to a single event”, with the outcomes readily observable; in contrast “Psychosocial health issues are … less direct and more complex in that they can depend on a number of organizational or personal factors”

Finally they cover the question “How do board activities influence OHS?”

Overall, there is “scarce empirical evidence” which covers the mechanisms that boards influence safety outcomes.

And, “Given the governing role of directors, it could be argued that they have little direct influence on OHS outcomes. The suggestions made in the findings is rather to influence OHS indirectly through culture, internal control, performance management and organizational structures”.