This systematic review covers strategies and tools used in healthcare patient safety for learning from normal work and Safety-II.

22 articles met inclusion.

For background:

· In healthcare “underreporting is highly prevalent, and is linked to, among other things, shaming and blaming mentality, insufficient visible measures and inadequate communication about errors”

· “most reporting systems do not facilitate learning and, hence, do not improve patient safety”

· “As the aftermath of errors, healthcare professionals may experience the second victim phenomenon including, amongst other things, burnout and depression”

· “The link between working climate and patient safety adds to the limitations of focusing on errors”

· “Safety-II is a new approach to patient safety that is characterised by learning from success”

· It has been well-received within healthcare practices because it “points out that most times things go well despite changing conditions and should be focused on and learned from”

· “Healthcare systems can be viewed as non-linear, unpredictable complex systems that constantly require healthcare professionals to adapt to the ever-changing conditions, such as shortcomings of staff, miscommunications, overflow of patients, etc., for keeping patients safe”

· And adding “More protocols to constrain how quality care is achieved are not always helpful, because protocols cannot possibly foresee every interaction that may affect the work”

Results

Overall, most learning tools were aimed at healthcare professionals in hospital units and “were generally welcomed by healthcare professionals”.

The second most frequent tools were aimed at learning across the organisation, then tools for learning between hospitals. Most of the studies focused on “validating the tools’ ability to provide insights into work-as-done, and their effect on staff wellbeing. Few studies focused on patient outcomes”.

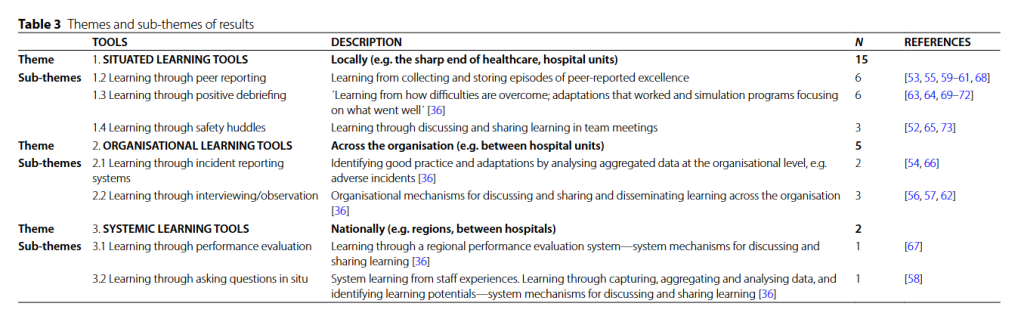

Tools were grouped into situated, structural, and systemic learning tools.

1. Situated learning tools: These were tools used by healthcare professionals at the frontline, and divided into three levels: tools for peer reporting, positive debriefing, and safety huddles. These were the most commonly described tools, where ‘Learning from Excellence’ the most frequently mentioned.

2. Organisational learning tools: these were tools used across units in the org, and divided into two levels. The first were tools based on learning through incident reporting systems and the other was for interviewing and/or observations

3. Systemic learning tools: These are tools to learn on a national or regional level and divided into two levels. The first was tools on learning through performance valuation and the other questioning in situ. These were the least mentioned tools.

Situated learning tools were used by healthcare professionals, like at the bedside. Learning from Excellence (LfE) is a peer reporting tool for a peer to report a colleague’s excellent performance.

Positive debriefing tools are used to systematically discuss episodes after delivering care. All six of included tools focused on structured sets of open questions for reflection, like “What went right? What helped or hindered? What can we learn from this?”.

Safety-II inspired huddles were multidisciplinary brief exchanges about work as done (WAD). It included how work went well. The huddles should take place regularly, like daily or weekly, and the “learning should be documented in a calendar”.

Organisational learning tools were used for learning across organisations. Incident reporting systems were adapted from a S-II view. One study explored the “common misalignments identified in the root cause analysis of Never Events” via this tool.

They found “that even the best root cause analysis was inefficient, and half of the misalignments were not associated with any actions”.

Other studies looked at tools involving interviews or observations to help understand WAD, focusing on “proactively identify[ing] system vulnerabilities and propose quality interventions to strengthen adaptive capacity”. The CARE tool is one example.

Systemic learning tools were used nationally or between hospitals. LfE was found in one study to have potential for promoting improvement processes, and “boost personnel resilience and the organisational working climate”.

Real-time data collection was also a focus via asking healthcare professionals questions in situ. These occurred during tasks, like normal blood transfusion, to unpack how things normally go wrong.

Conclusions

Overall, they argue that tools like peer reporting (LfE) and positive debriefing are relatively simple and feasible to implement and easy to understand. They “add value both to healthcare professionals` well-being and in providing a deeper understanding of ways to keep patients safe in a complex and ever-changing conditions”.

However, the “Safety-II focused safety-huddle tool Green Line … was not feasible to implement”. Frontline operators didn’t readily understand the underpinning concepts in the tool and found it hard to “learn from situations that had been resolved, as these experiences were taken for granted [65]. Verbally expressing tacit knowledge, such as in every-day WAD, is known to be difficult”.

Applying tools and strategies within S-II and resilience have been critiqued as “fleeting, ambiguous and disconnected from operational reality”, hampered by a lack of practical guidance on “how to operationalise the key concepts of Safety-II, such as learning from everyday work”.

Hence, a “pre-requisite for implementing Safety-II in healthcare is to translate the resilience concept into meaningful practical concepts”.

They note that it was surprising to see so many S-II tools, 16 in this study, and most published within the last 3 years considering that the “Safety-II perspective is in its infancy in healthcare“.

That is, a lot of S-II inspired tools have sprung up in the research in such a small period of time, and there’s lots, lots more in use that haven’t been studied.

They say the lack of extensive published guidance on learning from everyday work in healthcare is problematic. For one, “As learning does not just happen, which unfortunately is true for most learning systems, it is important to have a theoretical anchoring for developing future resilience learning tools”.

However, a “significant study” has explored what constitutes effective learning tools to learn from WAD. It found key constitutes: “using a collaborative approach, having high flexibility and usability and creating spaces for reflection where examples of good practice can be shared”.

Most of these tools focused on obtaining in-depth info about “WAD in practice”. CARE, for instance, works to understand work as done by healthcare professionals by “taking a neutral stance, studying how the goals are achieved despite difficulties”.

This perspective, therefore, “is the crux of Safety-II, as it mirrors the complexity of work, and not the linear WAI”.

Ref: Birkeli, G., Lindahl, A. K., Hammersbøen, Å. M., Deilkås, E. C. T., & Ballangrud, R. (2025). Strategies and tools to learn from work that goes well within healthcare patient safety practices: a mixed methods systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 25(1), 1-18.

Study link: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-025-12680-2

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/strategies-tools-learn-from-work-goes-well-within-mixed-hutchinson-c6loc