This study from Lingard and colleagues studied the types, causes and perceived consequences of safety clutter.

Sample was interviews with 18 construction industry participants.

For background:

· First they argue that “Contemporary safety management systems have been criticised for being impractical, duplicative, ill-fitting, excessive, wasteful, and ineffective”.

· Others argue that SMSs are “characterised by excessive rules, procedures, bureaucracy, and obligations that may not always contribute to improved operational safety outcomes”.

· The concept of safety clutter has been identified as a barrier to effective safety performance. According to Rae and Provan, clutter is the “accumulation of safety procedures, documents, roles and activities performed in the name of safety, but do not contribute to the safety of operational work”.

· Hence, it’s argued that not all safety practices inherently improve operational safety and some may “actually impede safety performance”. Examples include creating new rules after incidents which may not help address the issues, nor be required by law, completing excessive or irrelevant paperwork, duplicated processes, and paperwork that is never reviewed or used.

· Rae and Provan’s work delineated between safety work and the safety of work. Safety work are the activities/tasks done in the name of ‘safety’, whereas the safety of work is the actual prevention of harm during day-to-day operations.

· While, perhaps, a core aim of safety work is to have some direct impact on the safety of work, sometimes safety work “serve symbolic or bureaucratic functions rather than addressing real operational risks”.

Results

Interview data revealed safety clutter to be a “complex phenomenon that undermines effective safety management, while consuming significant organisational resources”.

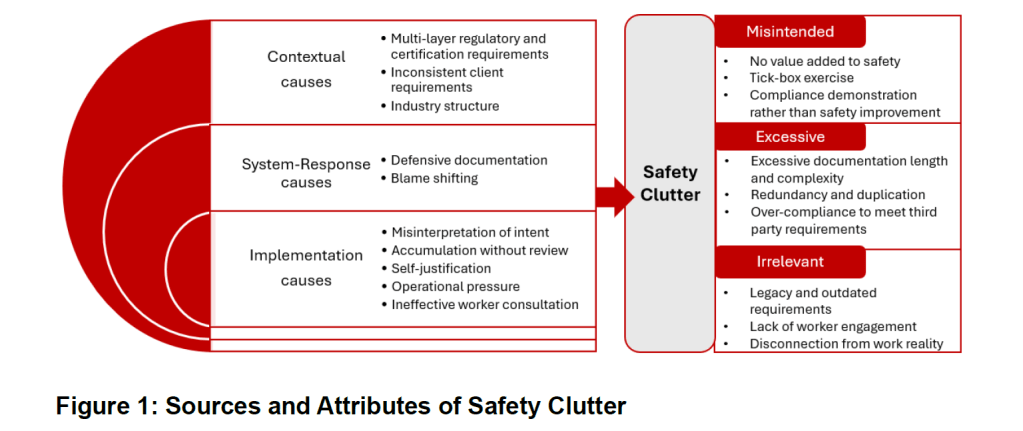

Safety clutter manifests through nine attributes, categorised as: misintended, excessive, or irrelevant practices. Further, these attributes emerge from ten causes across contextual, system-responses and implementation levels.

Attributes of Safety Clutter:

1. Misintended Practices as Clutter

Misintended safety clutter “consists of safety activities that provide no value to improving safety outcomes”.

Hence, these are activities that don’t meaningfully reduce risk or enhance protection, but still remain in practice.

One participant noted that “There’s a lot of paperwork that often doesn’t really serve a purpose. It’s there, we do it, it doesn’t really change safety outcomes, doesn’t improve site safety”. With that logic, “the effort invested in maintaining these activities far outweighs their benefit”.

Participants also believed that safety clutter contributes to a tick-box activity, focused on formality rather than substance. Safety activities are transformed into compliance activities over something which can prevent life altering injury.

Another participant observed that sometimes you look at safety work as “just a case of creating paperwork for the sake of having paperwork… it’s completely out of your control but you’ve got to make sure you comply”.

This shift, therefore, leads to “undermining the true purpose of safety systems”.

In all, misintended safety clutter contributes to no value added, tick-box exercises, and compliance demonstration.

2. Excessive Practices as Clutter

This highlights potentially valuable safety activities “implemented to such an extreme degree that they become counterproductive”.

For instance, documentation length and complexity, like with SWMS/JSAs. An example of a SWMS being 32 (or up to 60-90) pages, and the participant found it difficult to remember what they read.

But on top of the onerous SWMS, some have to also complete dynamic risk assessments, like Take 5s. Hence, the result of these onerous processes is “a layering of redundant processes that duplicate effort without enhancing safety”.

Audits were also implicated. One participant said they could be dealing with 4-5 external auditors over a 12-month period (internal and external, e.g. accreditation, clients, internal, and more).

Problematically, an “auditor may have a different view of the world. So you’re constantly changing, reviewing and updating your system to comply with an external body”.

[** My research, as with other audit research, supports this contention. Audits transform what they audit, into more auditable systems. This can transform a more bespoke system designed for more specific performance into a less functional, but more generalisable and auditable, system.]

Three attributes of excessive practices were: documentation length and complexity, redundancy and duplication, and over-compliance for third-parties.

3. Irrelevant Practices as Clutter

These are practices which are “disconnected from workplace realities [and] don’t reflect how work is actually performed or address genuine risks, creating a gap between formal safety systems and actual work practices”.

An example was with vehicles having extensive telematics, but drivers are still required to submit a paper journey management form, even though the telematics provide all of that info and more.

Hence, “Organisational inertia keeps outdated requirements in place even after their purpose has been superseded by new technologies or practices.”.

A lack of engagement with the affected stakeholders can also increase irrelevant processes, and therefore, “Safety processes created without frontline input fundamentally miss their purpose”.

Sources of Safety Clutter

Next they focus on perceived sources of safety clutter – namely resulting from “a complex interplay of forces operating at different levels within and beyond organisations”.

Hence, clutter arses from the “interactions between external pressures, organisational responses, and implementation practices”.

Construction typically has a complex regulatory and contracting landscape. One participant described OFSC and legislation having “slightly different requirements”. Then you add client requirements and different contractors into the mix.

E.g. “This regulatory complexity is further compounded by inconsistent client requirements, requiring contractors to maintain multiple parallel safety systems”.

System-Response Interactions: Organisational Adaptations

Their results indicate that “organisations don’t passively receive these external pressures but actively respond to them”, and this often has the effects of generating more clutter.

Defensive documentation was a prominent example, where “organisations create extensive paperwork primarily in an attempt to protect themselves from legal liability, rather than in the interests of safety improvement”.

[**Defensive medicine is also well-described in the research where doctors order unnecessary tests/scans to protect themselves, and defensive engineering where engineers over-design stuff. I also found defensive auditing in my audit research, where auditors request paperwork over and above what’s necessary.]

Defensive practices can lead to blame shifting. This is where “safety documentation becomes a tool for redirecting responsibility from organisations to individuals”. E.g. if something goes wrong, management can show how workers didn’t sign or complete the correct form and hence “try to put the blame back on the individual, rather than the system of work which has allowed that error”.

A misinterpretation of intent can result, where “the original purpose of safety regulations becomes distorted through excessive implementation”. This can result in extending documentation requirements beyond their intended scope.

More pervasive, it’s argued, is how safety requirements tend to accumulate without challenge but “are rarely pruned”.

Safety clutter also grows from self-justification processes where safety people and departments “develop complex systems partly to demonstrate their value to the organisation”.

Other issues include day-to-day operational pressures, which drive a wedge between formal safety systems and actual practices, and ineffective worker consultation.

They provide an example of how decluttering a process may have little benefit if “client auditing expectations still require exhaustive evidence, exacerbated by the inconsistent client requirements across projects”.

Further, quoting the paper:

“a builder might develop streamlined safety processes, but if principal contractors impose their own extensive requirements as defensive and blame shifting documentation against potential liability, the decluttering effort potentially becomes ineffective in practice”.

Operational Consequences

They say that safety clutter impacts operational effectiveness by:

· Causing resource misallocation by “diverting safety professionals from field activities to administrative tasks”

· one participant said because of misallocation, one week they may only spend 30% on the ground and 70% behind a computer

· it also leads to procedural ineffectiveness due to the volume of documentation

· it can also “result in risk management degradation by obscuring critical safety information”, by ‘clouding’ the focus on SIFs

· For others, clutter was seen as creating new hazards

Worker Consequences:

Clutter can result in consequences to workers:

· By leading to disengagement from safety processes that they find overwhelming or impractical

· Disengagement “manifests as workers circumventing requirements or taking shortcuts to avoid burdensome processes”

· It may also have a psychological impact on workers, leading to frustration and job dissatisfaction

· Onerous focus on clutter may also “disregard worker expertise by prioritising documentation over practical knowledge”

Business Consequences

Clutter can affect businesses:

· Financially, via increased resource requirements, productivity losses and program delays

· Damaging reputation of safety and relationships with stakeholders

· “Ironically, excessive documentation can create compliance issues. “If we have a process that says you have to have a written record of this, and then the written record is not completed, but the actual physical check is done, we’re non-compliant with our own system, and therefore we’re at risk”

Workplace Culture Consequences

The most significant impact, according to the authors, is that clutter can undermine the development of a positive workplace culture for safety:

· Namely, it “ erodes trust and credibility between workers and management”

· Onerous volumes of safety processes also impede communication effectiveness

· It also “distorts leadership and accountability within organisation”

· They argue that “As safety processes become increasingly cluttered, organisations lose their ability to properly lead safety efforts”

Ref: Lim, HW, Lingard, H., Zhang, R., & Pirzadeh, P. (2025). Decluttering Safety: A Multistakeholder Approach to Enhancing Safety Management in Construction: Position Paper. RMIT University, Melbourne

Shout me a coffee (one-off or monthly recurring)

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/decluttering-safety-multistakeholder-approach-ben-hutchinson-lvb6c