This 2002 discussion paper from Erik Hollnagel unpacks some assumptions of different accident models.

Note: In this work, accident model isn’t the specific tool or method (e.g. ICAM), but a “frame of reference as the accident model, i.e., a stereotypical way of thinking about how an accident occurs”. i.e. the mental models and justifications on how we think about causality.

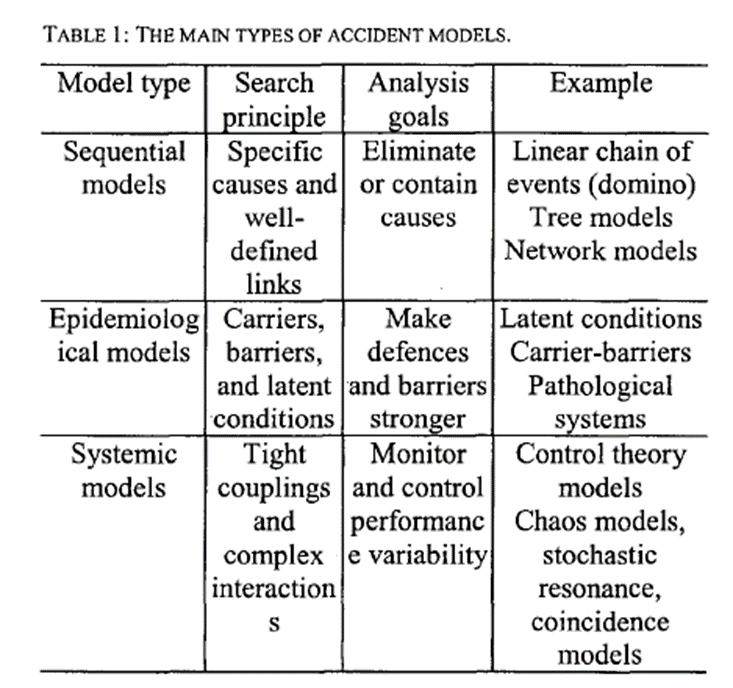

An overview of the models are below:

Sequential accident models

This is said to be the simplest accident model (** remember – frame of reference), which sees accidents as resulting from a sequence of events that occur in a specific order.

It’s been visualised in some work as a set of dominos, falling into the next domino and so forth.

Later examples include some barrier models, which describe accidents in terms of a linear and sequential failure of barriers.

Sequential models are “said to focus on what went wrong but in doing so leaves out additional information that may be potentially important”.

Sequential models often represent a single sequence of events, but don’t need to be, e.g. they also include event trees and the like.

Sequential models are “attractive because they encourage thinking in causal series rather than causal nets”. They’re also easy to represent graphically, making them easier to communicate.

Hollnagel argues that while sequential models served us well for the first half of the 20th century, “, they turned out to be limited in their capability to explain accidents in the more complex systems that became common in the last half of the century”.

Epidemiological Accident Models

Next as what he calls epidemiological models, based on an analogy of accidents like diseases. E.g. a combination of active and latent factors, some lying dormant for some time.

Examples include the Swiss Cheese metaphor, and the blunt and sharp-end analogy.

Epidemiological models are argued to be valuable because they “provide a basis for discussing the complexity of accidents that overcome the limitations of sequential models”.

The very notion of latent factors “simply cannot be reconciled with the simple idea of a causal series, but requires a more powerful representation”. Epidemiological models, therefore, push efforts beyond simple causes, towards understanding more complex interactions among different factors.

In any case, Hollnagel argues that “epidemiological models are rarely stronger than the analogy behind, i.e., they are difficult to specify in further detail”. Therefore, the metaphor, analogy or model itself becomes the most limiting factor. (** I’m less convinced of this…but whatever)

Systemic Accident Models

Third are systemic models. These describe the characteristics and performance on the level of the whole system, rather than on the specific cause-effect mechanisms.

Systemic models don’t strive to structurally decompose the system, but instead considers emergent phenomena from the interactions. They have their basis in control theory, chaos models and elsewhere.

He argues that systemic models, generally, highlight the need to “base accidents analysis on an understanding of the functional characteristics of the system, rather than on assumptions or hypotheses about internal mechanisms as provided by standard representations of, e.g., information processing or failure pathways”.

Accidents can’t be described as just causal series or a causal net, since “neither representation is incapable of accounting for the dynamic nature of the interactions and dependencies”.

Further, these models “deliberately try to avoid a description of an accident as a sequence or ordered relation among individual events”. As such, they’re typically more difficult to graphically represent or communicate.

Some Assumptions of each Model

Sequential models are said to typically search for specific causes and cause-effect links. The governing logic is that the accident resulted from a sequence of events and the causes can be found.

Epidemiological models typically focus on the search for active and latent factors. They may also look for performance deviations with the “recognition that these can be complex phenomena rather than simple manifestations”.

A logic of epidemiological models is that defences and barriers can be put into place at each hierarchical level.

Systemic models shift the search towards unusual dependencies and common conditions. From this perspective, there will always be “variability in the system and that the best option therefore is to monitor the system’s performance so that potentially uncontrollable variability can be caught early on”.

From this view, variability in itself isn’t an inherently bad thing, and efforts shouldn’t be on trying to eliminate it at all costs. To the contrary, “performance variability is necessary for users to learn and for a system to develop; monitoring of variability must be able to distinguish between what is potentially useful and what is potentially harmful”.

He importantly argues that one mode is not unequivocally better than the others. While he cautions the sole use of sequential models, it “should not be discarded outright”.

Indeed, there are cases where easily distinguishable causes can be identified and it “makes sense to try to eliminate them”. Further, we shouldn’t shy away from barrier-thinking.

Nevertheless, we shouldn’t try to oversimplify things that don’t warrant oversimplification. As he argues, “Although complexity is difficult to handle, both in theory and in practice, it should not be shunned”.

ROLE OF HUMANS IN ACCIDENTS

Off-the-bat, Hollnagel argues that while humans are no longer seen as the primary cause of accidents, “they do play a role in how systems fail – as well as in how systems can recover from failure”.

This is often because people are, simply put, an indispensable part of all complex systems. People design, install, use, maintain systems. No technological system “has created itself or can take care of itself, and humans are involved from the very beginning to the very end”. [** Maybe this logic will shift a bit when machine learning creates iterations of itself far-removed from the original programming logics]

While the original focus was on sharp end factors, the role of people is now also evident at the blunt end, and everywhere in between. Quoting Karlene Roberts, “everybody’s blunt end is somebody else’s sharp end”.

He maintains that while systemic models call for systems thinking – this also doesn’t automatically mean “analysis should attempt to follow the antecedents back to the origin of the system – or even beyond that.”

Indeed, this type of approach is said to be a misinterpretation of the sharp-end/blunt-end logic, since it may also imply that there is some direct cause/effect relationship. Instead, this logic should be understood as “actions or decisions at any level may have effects that only manifest themselves much later”.

He says if one wants to understand the role of humans in an accident, a first step is to recognise that human actions can’t be described in binary terms – being just either correct or incorrect.

A reason why is that such judgements can only be made in hindsight, with knowledge of the outcome. Further, he suggests that “It must be assumed that people always try to do what they think is right at the time they do it”. For instance, assuming that the operators at Chernobyl or Three Mile Island tried to bring about a nuclear incident is a grave misapplication.

Instead, “Their actions turned out to be disastrously wrong because the operators did not understand the situation”, and other reasons.

Hollnagel provides examples of human actions (from Amalberti), below:

Assumptions of each accident model towards the role of humans?

Next he discusses how each model approaches the role of humans in accidents.

The sequential model assumes there is a causal chain and “Each event in this chain is considered as either being done correctly or as having failed, and this goes for human actions as well as anything else”.

In his view, in the sequential models there is “no room for the multifaceted view of human actions” proposed above. He says that this is reason enough not to base an entire analysis on sequential logics. Sequential models also make it difficult to consider more complex phenomena.

In the epidemiological models, human actions, or sometimes unsafe acts, are triggers at the sharp-end, but rarely ‘causes’ of accidents. Instead, the accidents come about because of an “unforeseeable concatenation” of unsafe actions and latent conditions”, with latent conditions often being removed in space and time (blunt end) from the active factors and hazard (sharp end).

The systemic model is based on the notion that human actions are variable and variability is the central issue, not human failures.

Therefore, it’s critical to understand how and why human actions vary. Drawing on Weick’s quote, “safety is a dynamic non-event”. Meaning that safety is more than the absence of incidents but rather depends on “dynamic characteristics of the system”.

Moreover, “It is the way in which the system behaves, including the people in the system, which creates safety and accidents alike”.

He argues then, that the variety of human actions as above must be supplemented by a model or description of how those actions occur.

ETTO (Efficiency-Thoroughness Trade-off)

One explanation for those human actions relates to ETTO. Human performance “must always satisfy multiple, changing, and often conflicting criteria”.

Humans are usually pretty good at navigating imposed complexity, because they can adjust what they are doing and match current conditions. Therefore, people are always trying to “optimise their performance by making a trade-off between efficiency and thoroughness”.

People try to genuinely meet task demands and be as thorough as they believe is necessary. Meanwhile, they do this while being as efficient as possible. This avoids unnecessary effort or waste.

There is variability in everything, but generally it’s because we have some degree of stability and predictability in organisational work that people are able to optimise their performance.

Hence, human performance is efficient “because people quickly learn to disregard those aspects or conditions that normally are insignificant”. This is said to not just be a convenient ploy for the individual, but “a necessary condition for the joint system (i.e., people and technology seen together)”.

Therefore, this connection between people and their environment “creates a functional entanglement, which is essential for understanding why failures occur”.

Hollnagel argues that “As far as the level of individual human performance is concerned, the local optimisation – through shortcuts, heuristics, and expectation-driven actions – is the norm rather than the exception”.

We should expect optimising behaviour from people, and therefore normal performance “is not that which is prescribed by rules and regulation but rather that which takes place as a result of the adjustments, i.e., the equilibrium that reflects the regularity of the work environment”

In concluding, he argues:

· Normal performance and failures are emergent phenomena, which can’t be attributed to the constituent parts

· For the role of people in failure, this results largely from variability of the context and conditions rather than to action failures on their part

· Adaptability and flexibility of people is the reason for efficiency in systems, but “is also the reason for the failures that occur, although it is never the cause of the failures”

· “If anything is unreasonable, it is the requirement to be both efficient and thorough at the same time – or rather to be thorough when with hindsight it was wrong to be efficient”

Ref: Hollnagel, E. (2002, September). Understanding accidents-from root causes to performance variability. In Proceedings of the IEEE 7th conference on human factors and power plants (pp. 1-1). IEEE.

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/understanding-accidents-from-root-causes-ben-hutchinson-v4hgc