This 2016 article from Fred Manuele explores some facets of causality in investigations.

It’s based mainly on two key sources: Hollnagel’s 2004 ‘Barriers and accident prevention’ and Dekker’s 2006 ‘Field Guide to Understanding Human Error’.

Won’t be much new for most but has some nice arguments from authors like Hollnagel, Dekker and Leveson.

First he asks us to consider some commentary from Hollnagel & Dekker:

1) Incidents can be discussed in many ways and “the cause-effect assumption is perhaps the least attractive option”

2) Incident models (including mental models of how incidents happen) tend to reinforce a search for ‘causes’ rather than explanations

3) “Root cause is a meaningless concept”

4) Instead, what “you call root cause is simply the place where you stop looking any further”

5) “Where you look for causes depends on how you believe incidents happen”

Hollnagel’s arguments:

Some key arguments from Hollnagel’s work is that adopting cause/effect approaches tends to be the “least attractive” of all options. This is because causes or contributing factors not necessarily occur sequentially in complex events.

However in non-complex situations, cause/effect may be adequate.

Hollnagel suggests that we should describe incidents as narrative descriptions “rather than seeking causes”. This necessarily includes understanding the difference between explanations of the hows and whys versus ‘causes’.

Hollnagel and Dekker are both critical of the ‘root cause analysis’ approach. For Hollnagel, this method is “less-than-adequate” and actually “deceptive”. It’s deceptive and meaningless from the perspective of being able to source one and only ‘root cause’ of a problem.

Moreover, practicably, “the investigation process stops when those involved conclude that their inquiry has reached its cultural and organizational limits”.

Hollnagel did concede a definition of cause, though, being:

“A cause can be defined as the identification, after the fact, of a limited set of aspects of the situation that are seen as the necessary and sufficient conditions for the observed effect(s) to have occurred”.

Further, Hollnagel suggests that while determining/constructing causes is a “relative and pragmatic venture”, it is not scientific.

He also warns about the search for constructing causes over explanations. In any case, the value of both derive from constructively taking action, rather than trying to necessarily derive “true” causes.

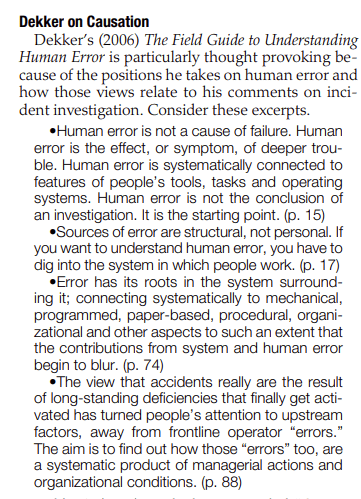

Dekker’s arguments

Some excerpts from Dekker are provided. I’ve provided these in the below image, but simply:

· “Human error is not a cause of failure” but is “the effect, or symptom, of deeper trouble”

· It’s “systematically connected to features of people’s tools, tasks and operating systems”

· Human error is not the conclusion of an investigation. It is the starting point”

· Sources of error are structural and not personal

Dekker argues that “there is no such thing as the cause”. Instead, cause is “something we construct, not find”. Importantly, how we construct cause depends on our accident model (mental model and worldviews).

Fred Manuele agrees that the investigator’s beliefs shapes what they find and construct in investigations; that is, it’s “an important truism that should prompt extensive introspection and self-analysis by safety practitioners”

He provides the example that if an investigator believes unsafe acts by workers is the principal cause of accidents, then they’re likely to find (construct) that.

Also in Fred’s view, searches for causal/contributing factors in investigations tend to be “dismally shallow and is neither found nor created”…Ouch.

Both Hollnagel and Dekker concur that there is no root cause, and what is called a root cause is “simply the place where you stop looking any further”.

Again it’s highlighted that investigators should write about explanations over causes. The focus on narrative provides a richer description for understanding and improvement, and the context for issues and events. It also provides the opportunity for the investigator to describe what they believe to be important (being upfront about worldviews).

Models of Incident Causality

Next the paper covers different core types of incident causality model. Note that this isn’t talking about ICAM, HFACS, but rather the mental models we have about how accidents occur.

I covered some of these recently in another paper by Hollnagel, so not covering them again. But it includes sequential, epidemiological and systems models.

Which frame the investigator takes will shape how they construct meaning.

Further, the issue of stop rules is discussed. A stop rule is “the point at which action can be defined or additional proof of cause is no longer necessary for the purpose of analysis”. If somebody sees accidents as largely resulting from behaviour, then the stop rule may be triggered after constructing the role of behaviour.

Stop rules also include time and resource limits. For Hollnagel, “Investigations typically stop too soon, thereby avoiding recognition of the management systems deficiencies that could be important”.

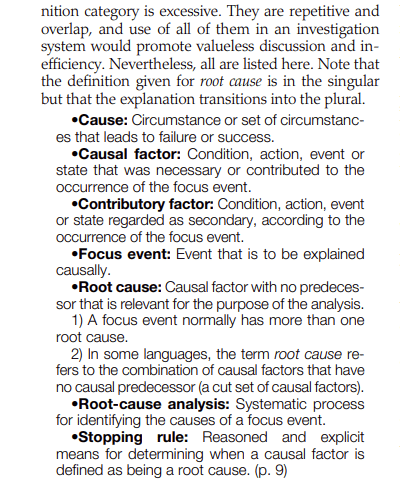

Causes

Next the topic if causes is expanded on. Again it’s recognised that the inherent model an investigator has determines what sort of factors will be sought in the investigation. Whether the investigator knows it or not, how they think about accident causality shapes what they find/construct.

Manuele provides some definitions showing how much overlap and unnecessary repetition is present:

5 Whys

Next for some reason, Manuele discusses the 5 Whys technique. Not sure why this is here, and not any other technique, but, whatever.

First he says that some “consider the five-why problem-solving technique to be overly simplistic”. Despite this criticism, he strongly recommends 5 Whys as an initial starting point for improving investigation quality (I assume for less mature organisations?).

He provides a few examples. One is a tool cart tipped over, injuring a worker.

A 5 Whys may go something like: (I’ve skipped a lot of it)

1) Why did the cart tip over? Hows…

2) Why weren’t the previous incidents report? Hows…

3) Why is the diameter of the castors too small? Hows…

4) Why did the fabrication shop make carts with castors that are too small? Hows…

5) Why did engineering give fabrication castor dimensions that were known to be too small? Hows…

And etc.

Again he says that some people criticise 5 Whys for not necessarily addressing management system deficiencies. Here he says that “Safety professionals must understand that when this technique is applied to complex operations, the results may indicate that a more sophisticated causal factor determination system is needed”.

Conclusion

In all Manuele argues that safety people should consider their mental models, time available organisational limits.

And if the investigation process “recognizes deficiencies in management systems, the place at which investigators stop may be at the realistic organizational boundary”, rather than at the level which is necessary to resolve the issue.

Conversely, while some argue that investigations should dive into how each management system deficiency came to be. Here Manuele counters that, “While that would be nice to do”, it may not be realistically possible.

He argues that if the current investigation approach is identifying multiple contributing factors and is driving learning and goal improvement, then there may be little need for change.

Ref: Manuele, F. A. (2016). Root-Causal Factors: Uncovering the Hows & Whys of Incidents. Professional Safety, 61(05), 48-55.

Study link: https://aeasseincludes.assp.org/professionalsafety/pastissues/061/05/F1_0516.pdf

LinkedIn post: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/root-causal-factors-uncovering-hows-whys-incidents-ben-hutchinson-v87ic